Seeds

Marleen Boschen

Related terms: agriculture, botanic gardens, botany, community, imperial botany, kin, life form, plants.

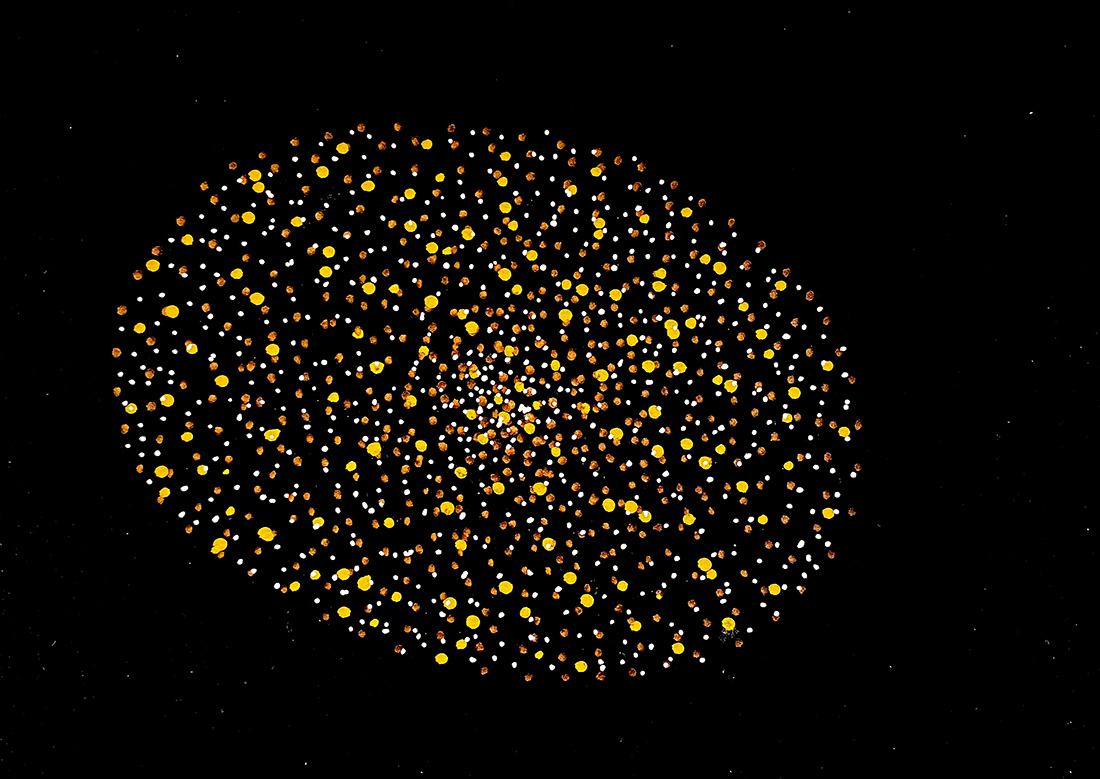

“We’re trying to recover the spirits of the seeds,” says artist Cristina Ochoa when speaking of the Cosmic Seed Basket (personal communication, 2025). This is a project she has been developing for the summer of 2025 as an installation in the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, in Wakehurst, Sussex, in the UK. Over many years, the Colombian artist has collaborated with Mayan, Totonac, and Mexica elders as well as others across South America to gain a profound understanding of the healing and spiritual abilities of plants and seeds as carriers of memory. For the Cosmic Seed Basket, she has been listening to and sonifying the seeds of Colorín (Erythrina americana), a beautiful, bright orange, and shiny seed. For Ochoa, these seeds are speculative time-travellers and, when ingested, have both paralysing and psychoactive effects on the body and mind. The Cosmic Seed Basket is grounded in the voice of the Colorín seed, the Totonac tradition of Veracruz, Mexico, and the voice of Doña Juana González, a healer. Doña Juana described to Ochoa how seeds have protective spirits. The artist was invited by Kew to respond to Kew’s global seed partnership for wild plant seeds, and specifically to work with its seed collection programme in Mexico. When considering how to work with these seeds that are sacred to many Indigenous practitioners, Berito Kuwaru’wa of the Uwa people in Colombia told Ochoa that the seeds’ spirits needed to be reconnected following a separation through the process of seed conservation and storage in Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank, the planet’s largest ex-situ collection of wild plant seeds. When artists are invited into spaces of global plant conservation and plant science, how might we understand the spirit of a seed, or indeed what a seed is at its core?

Throughout this text, which explores the divergent meanings of what a ‘seed’ can be, and to whom, Ochoa’s Cosmic Seed Basket offers an invitation: to take the embodied relations and shared knowledges between seeds and their custodians seriously. I am thus deeply grateful for the work of Ochoa and her collaborators, and I ground this exploration of the multiple meanings of ‘seeds’ in the practices of two artists. Food sovereignty activist and artist Zayaan Khan’s work, including the Seed Biblioteek in Cape Town, South Africa, is also a long-standing and meaningful point of inspiration. Started to support a farming land occupation, the Seed Biblioteek is a communal and living seed collection, a practice of resistance and a carrier of knowledge, relations, and interspecies belonging. It reconnects ‘seed with story, towards resilience and sovereignty’ (‘Seed Biblioteek (@seedbiblioteek) • Instagram Photos and Videos’, n.d.) through community gatherings and exchanges, reclaiming seeds and their stories in a context where industrial seed production in South Africa is curtailing farmers’ rights. Across her practice and research, Khan advocates for a shift from understanding ‘seed-as-object’ to ‘seeds-as-relation’ (Khan 2025). Taking Ochoa’s and Khan’s practices as anchor points, before considering a more biological understanding, this glossary entry holds artistic and eco-poetic understandings of ‘seeds’ alongside practices of care in seed conservation. It thus explores the potential of environmental humanities practice and research to attend to divergence and multiplicity in how we relate to and meet ecological others. What is a ‘seed’? And how does a relational approach to thinking with seeds speak to questions of land, sovereignty, and care amid a loss of worlds in an accelerating ecological crisis? How do artistic practices attend to human-plant relations and becomings?

Approached through the lens of an arguably historically Eurocentric plant science, a ‘seed’ is one stage in a plant’s lifecycle. Flicking through the folders that contain the learning printouts of the globally renowned seed conservation course at Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank, I came across the following teaching definition while spending time at the seed bank for research and interviews: a ‘seed’ is a “mature and fertilised plant ovule”; it is “the unit of reproduction of a flowering plant, capable of developing into another plant” (Royal Botanic Gardens Kew 2025). As encyclopaedic definitions of ‘seeds’ often highlight, a seed carries the embryo of a future plant inside; it includes carbohydrates and genetic information (‘Seed - Gymnosperm, Embryo, Structure | Britannica’, n.d.). Xan Chacko and Susannah Chapman describe the fertilised embryos within seeds as “maybe-babies,” a lens that puts seeds in a wider seed ecology of relations and generations (Chapman and Chacko 2022). A seed thus holds both a past and a future plant. This state between generations, a state of dormancy awaiting germination, is one of the reasons seeds invite evocative human imaginaries and have been fascinating subjects for artists and practitioners across the environmental humanities, the plant humanities, or critical plant studies. Indeed, they have their own future-oriented agency, sensing environmental cues when to initiate germination. Seeds are strategic in this way: they await germination until conditions are as ideal as possible. Seed dispersal, a slow process of plant migration, provides the seed, which is (mostly) incapable of motoric movement, with an opportunity to travel, for instance, through wind (anemochory), water (hydrochory), and living organisms (zoochory) (Bewley et al. 2012). This scientific lens offers one way of meeting seeds by trying to capture and describe their processes and temporalities. Yet they are also complex collaborators in cultural and ecological imaginaries.

At a moment when the multiple crises of the present, their scales of loss, and the finality that is extinction feel overwhelming and scholars seek to understand what it means to write through these threats to collective survival (Van Dooren 2014; Rose 2017), seeds have become hopeful carriers of resilience (traditionally understood as an ability to recover from difficulty (Ekman 2025)) and adaptation (a process of becoming better suited to an environment or context) amid rapidly changing ecological conditions. One example is the growing research on “wild relatives,” those varieties that form the pre-domesticated ancestors of now domesticated, and thus more vulnerable, crop seeds (Castañeda-Álvarez et al. 2016). In scholarly discussions of human-vegetal ecologies, seeds appear as valuable resources of conservation in colonial botany, forestry, industrial agriculture, and agri-science (Eastwood et al. 2015; Fenzi and Bonneuil 2016; Curry 2017; Hartigan 2017; Montenegro de Wit 2017). They also gather interest as speculative beings with agency in the context of critical plant studies (Marder 2012; Marder 2013; Myers 2015; Irigaray and Marder 2016), as mobile subjects of hybrid geographies (Whatmore 2002), and as biocultural carriers of “wild memory” (Bristow 2015). For others, seeds are ethico-political kin and collaborators in struggles for sovereignty in agroecology (Nazarea, Rhoades, and Andrews-Swann 2013; Aguila-Way 2014), and carriers of survival amid multispecies extinctions (Van Dooren 2017). ‘Seeds’ are multiple in meaning and matter across these registers and practices. Entangled in histories of domestication and cultivation, Rodney Harrison sees a seed as “a biosocial archive in its own right” (Harrison 2017, 85), considering how the genetic material of crop seeds holds records of cultural selection and crop experimentation and describes agricultural histories, yet also connects to pre-domestication. However, Khan and Ochoa’s artistic practices with seeds, and the Indigenous seed custodians with whom Ochoa collaborates, powerfully reveal a different time-bending, transformative, and regenerative potential of seeds as carriers of relational memories and of story. This goes far beyond a scientific understanding of ways of being with seeds and plants as kin through embodied relations and is present in many seed-saving practices.

What emerges is a divergent sense of ‘seeds’ and multiple ecological imaginaries that are implanted in seeds beyond those seeds that are held as hopeful representatives of entire species in seed banks – frozen repositories that extend seed longevity, such as the Millennium Seed Bank at Kew or the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. In many ways, the seeds held in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault or circulating in industrial agriculture have been turned into “dispossessed” commodities and means of production on which the food security of millions of people often depends (Kloppenburg 2010).

Seeds carry a plethora of ways in which, as humans, we have inscribed ourselves into them, and vice versa. A seed is an embodied archive of relations, a portable time-traveller that “can bring past relations, persons, and places into the present” (Chapman and Chacko 2022, 358). Donna Haraway early on summarized the bodily, layered complexity of seeds from a feminist philosophy of science perspective: “a seed contains inside its coat the history of practices such as collecting, breeding, marketing, taxonomizing, patenting, biochemically analyzing, advertising, eating, cultivating, harvesting, celebrating, and starving” (Haraway 1997, 129). She understands seeds as part of a “set of objects into which lives and worlds are built” (Haraway 1997, 11). It is this sense of “seed-as-world” that I want to hold on to via Khan’s proposal of “seed-as-relation,” i.e., as embodied practices and knowledges. Similarly, Thom van Dooren describes seeds as archives of “inter-generational, inter-species, human/plant kinship relations” (Van Dooren 2007, 83). This amounts to recognising ‘seeds’ as miniature worlds of relations. Considering Ochoa’s work with Indigenous elders and the cosmological importance of ‘seeds’ here, where, for instance, the Colorín seed is trusted to tell the future and played an important role in Mayan creation stories, yet a different relation emerges: that of ‘seed as cosmos.’ Faced with the cultural significance of these cosmologies, I want to acknowledge here the tensions of having engaged with Indigenous knowledges indirectly, via Ochoa’s practice and her collaborators, and of drawing those knowledges into a canonisation within the wider context of this Environmental Humanities glossary. Unable to offer elders a way to share their stories and knowledge directly, writing through them, and the artwork that they have contributed to, becomes a process of representation that might distort, appropriate or misunderstand.

What a seed is, what seeds are, cannot be answered in stable ways, an insight echoing the plural title ‘Seeds’ for this entry. From Ochoa’s intention to reconnect seeds with their spirits and Khan’s intention to create a library to hold onto the seeds’ connections to the land and stories we have moved through practices and histories of commodification, preservation, and cultivation. Left with a multitude of relations, representational challenges, and agential forces contained in ‘seeds,’ their meaning shifts across contexts and translations, but also across seed-saving custodians. As Ochoa and Khan powerfully point out, ‘seeds’ are deeply tied to land, place, and people, and in this way to formations of more-than-human sovereignty. Thinking with the practices of artists has allowed for a ‘seed’ to emerge that is multiple, regenerative, relational, and often “fugitive” (Keeve 2020).

Speculative fiction writer Octavia Butler was also drawn to thinking with ‘seeds’ about the building of community and liberation. In her novel Parable of the Sower, the protagonist Lauren Olamina chooses “Earthseed” as the name for the community she seeks to build, and she beautifully opens up the many ways of being contained in being with and being moved by ‘seeds’:

Well, today, I found the name, found it while I was weeding the back garden and thinking about the way plants seed themselves, windborne, animalborne, waterborne, far from their parent plants. They have no ability at all to travel great distances under their own power, and yet, they do travel. They don’t have to just sit in one place and wait to be wiped out. There are islands thousands of miles from anywhere – the Hawaiian Islands, for example, and Easter Island – where plants seeded themselves and grew long before any humans arrived. Earthseed. I am Earthseed. Anyone can be. Someday, I think there will be a lot of us. And I think we’ll have to seed ourselves farther and farther from this dying place (Butler 2019, 73).

What Octavia Butler leaves us is, among many things, a thinking with seeds that opens up – via the imaginary of the portable and adaptable seed – the planting of a powerful sense of more-than-human community in the face of loss and destruction. Moving across the methodologies of speculative fiction and artistic practice, I have sought to position seeds as both (re)generative and shifting subjects and collaborators that encourage spatially and temporally expansive ecological storytelling for practitioners in the environmental humanities. There is an ever-expanding plethora of artists who are drawn to working with seeds including artworks such as Jumana Manna’s Wild Relatives (2018), Cooking Sections’ Rights to Seeds, Rights of Seeds (2025), Maria Thereza Alves’ Seeds of Change (1999-ongoing), Larissa Sansour’s In Vitro (2019) and Leone Contini’s Foreign Farmers (2018), to name just a few. As one of my interlocutors put it during my PhD research at the Kostrzyca Forest Gene Bank in Poland: “a seed is a mystery that hasn’t happened yet.” In this vein, I have tried to stay with the complexity of human-plant relations, the entanglements of biosocial and biocultural histories, that seeds carry into unknown futures.

References

Aguila-Way, Tania. 2014. “The Zapatista ‘Mother Seeds in Resistance’ Project: The Indigenous Community Seed Bank as a Living, Self-Organizing Archive.” Social Text 32 (1 (118)): 67–92.

Alves, Maria Thereza. Seeds of Change. 1999-ongoing. Site-specific installations, various locations. https://www.mariatherezaalves.org/works/seeds-of-change

Bewley, J. Derek, and M. Black. 2012. Physiology and Biochemistry of Seeds in Relation to Germination: Volume 2: Viability, Dormancy, and Environmental Control. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Bristow, Tom. 2015. “’Wild Memory’ as an Anthropocene Heuristic: Cultivating Ethical Paradigms for Galleries, Museums, and Seed Banks.” In The Green Thread: Dialogues with the Vegetal World (Ecocritical Theory and Practice), edited by Patrίcia Vieira, Monica Gagliano and John Ryan, 81-106. New York: Lexington Books.

Butler, Octavia E. 2019. Parable of the Sower. London: Headline Publishing Group.

Castañeda-Álvarez, Nora P., Colin K. Khoury, Harold A. Achicanoy, Vivian Bernau, Hannes Dempewolf, Ruth J. Eastwood, Luigi Guarino, et al. 2016. “Global Conservation Priorities for Crop Wild Relatives.” Nature Plants 2 (4): 1–6.

Chapman, Susannah, and Xan Sarah Chacko. 2022. “Seed: Gendered Vernaculars and Relational Possibilities.” Feminist Anthropology 3 (2): 353–61.

Contini, Leone. Foreign Farmers. 2018. Installation. Manifesta12, Palermo.

Cooking Sections. Rights to Seeds, Rights of Seeds. 2025. Installation. Museo delle Civiltá, Rome.

Curry, Helen Anne. 2017. “Breeding Uniformity and Banking Diversity: The Genescapes of Industrial Agriculture, 1935-1970.” Global Environment 10 (1): 83–113.

Eastwood, Ruth J, Sarah Cody, Ola T Westengen, and Roland Bothmer. 2015. “Conservation Roles of the Millennium Seed Bank and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.” In Crop Wild Relatives and Climate Change, 173–86. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Ekman, Ulrik. 2025. “Resilience.” Environmental Humanities Glossary: Emergent Key Terms, edited by Ulrik Ekman and Daniel Irrgang. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen.

Fenzi, Marianna, and Christophe Bonneuil. 2016. “From ‘Genetic Resources’ to ‘Ecosystems Services’: A Century of Science and Global Policies for Crop Diversity Conservation.” Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment 38 (2): 72–83.

Haraway, Donna. 1997. Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan_Meets_OncoMouse: Feminism and Technoscience. New York: Routledge.

Harrison, Rodney. 2017. “Freezing Seeds and Making Futures: Endangerment, Hope, Security, and Time in Agrobiodiversity Conservation Practices.” Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment 39 (2): 80–89.

Hartigan, John Jr. 2017. Care of the Species: Races of Corn and the Science of Plant Biodiversity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Irigaray, Luce, and Michael Marder. 2016. Through Vegetal Being: Two Philosophical Perspectives. Through Vegetal Being. New York: Columbia University Press.

Keeve, Christian Brooks. 2020. “Fugitive Seeds.” Edge Effects, February 25.

Khan, Zayaan. 2025. “Making Heritage through Seed Stories.” In Alternative Economies of Heritage: Sustainable, Anti-Colonial and Creative Approaches to Cultural Inheritance, edited by Denise Thwaites, Bethaney Turner and Tracy Ireland, 114-123. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kloppenburg, Jack. 2010. “Impeding Dispossession, Enabling Repossession: Biological Open Source and the Recovery of Seed Sovereignty.” Journal of Agrarian Change 10 (3): 367–88.

Manna, Jumana. Wild Relatives. 2018. Film, 64 min.

Marder, Michael. 2012. “Plant Intentionality and the Phenomenological Framework of Plant Intelligence.” Plant Signaling & Behavior 7 (11): 1365–72.

Marder, Michael. 2013. Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life. New York: Columbia University Press.

Montenegro de Wit, Maywa. 2017. “Stealing into the Wild: Conservation Science, Plant Breeding and the Makings of New Seed Enclosures.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (1): 169–212.

Myers, Natasha. 2015. “Conversations on Plant Sensing: Notes from the Field.” Nature and Culture 3: 35-66.

Nazarea, Virginia D., Robert E. Rhoades, and Jenna Andrews-Swann. 2013. Seeds of Resistance, Seeds of Hope: Place and Agency in the Conservation of Biodiversity. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Ochoa, Cristina. The Cosmic Seed Basket. 2025. Installation. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew Wakehurst. https://www.kew.org/wakehurst/whats-on/seedscapes/programme.

Rose, Deborah Bird. 2017. “Reflections on the Zone of the Incomplete.” In Cryopolitics: Frozen Life in a Melting World, edited by Joanna Radin and Emma Kowal, 145–55. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, 2025. Seed Conservation Techniques | Kew. Accessed 2 September 2025.

Sansour, Larissa. In Vitro. 2019. Two-channel film, 28min.

“Seed Biblioteek (@seedbiblioteek) • Instagram Photos and Videos.” n.d. Accessed 30 May 2025.

“Seed - Gymnosperm, Embryo, Structure | Britannica.” n.d. Accessed 24 July 2025.

Van Dooren, Thom. 2007. “Terminated Seed: Death, Proprietary Kinship and the Production of (Bio)Wealth.” Science as Culture 16 (1): 71–94.

Van Dooren, Thom. 2014. Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction. Critical Perspectives on Animals. New York: Columbia University Press.

Van Dooren, Thom. 2017. “Banking the Forest: Loss, Hope, and Care in Hawaiian Conservation.” In Cryopolitics: Frozen Life in a Melting World, edited by Joanna Radin and Emma Kowal, 259–82. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Whatmore, Sarah. 2002. Hybrid Geographies: Natures, Cultures, Spaces. London: SAGE.