Tidal Rhythms

Laura Vargas and Diego Cagüeñas

Related terms: care, nonhumans, species, water, scarcity, imagination, extinction, Anthropocene

I.

This entry is about care between distinct lifeforms. It follows reparative and protective work with creatures whose species-future is in peril (Rose 2017, 56) in search of caring relations that counter the destruction and violence that every racialised, extractive economy demands (Cruz Hernández 2020; Gómez-Barris 2017; González 2019). It is grounded on chance encounters among a mollusc, a human hand, and a measuring device in which an entire political ecology is enacted amid the muddy soil and entangled roots of the Colombian mangrove. We contend that this political ecology can be understood and embodied only once one attunes oneself to the tidal rhythms of the Pacific Ocean that orchestrate a mollusc’s reproductive life and the livelihoods of the Afro-Colombian peoples that inhabit Bahía Málaga, southwest Colombia. This entry also abides by these tidal rhythms to explore how a local ecopolitical imagination (Cagüeñas, Galindo and Rasmussen 2020) provides alternative forms of knowing, inhabiting, and caring, instead of feeding racial extractivism.

For centuries, the tidal rhythms of the Pacific Ocean, presided over by the moon, have governed how and when chance encounters among multifarious lifeforms could take place. For centuries, black people have harvested piangua, for that is the mollusc’s name, in synchrony with the ocean’s puja and quiebra, the high and low tides that renew the cycles of life and death. Earth beings find each other, if only fleetingly, before each takes leave. Sometimes they return, with the ebb of tides, lunar cycles, or wind currents, giving the semblance of certainty, as if life will forever flow with the highs and lows of waters.

That is, until recently, when this molluscoid, human, oceanic, and lunar choreography has gone out of sync. The mollusc has grown scarce. Hence, the measuring device in Figure 1, the piangüímetro. This deceivingly simple act of scaling down large swaths of time and translating into centimetres complex life cycles expresses the ecopolitical desire to foster engagements that respect tidal rhythms while providing sustenance for all earth beings that populate Bahía Málaga. It is a labour of care.

II.

By ‘ecopolitical imagination’ we mean communal and deliberate practices that aim to bring to life a future shared home that safeguards the communality of every form of existence. It aims to imagine a future time in which the scope of politics is broadened so that dependency relations between humans and more-than-humans are restored and fostered. Questioning the Western divide between nature and culture, ecopolitical imagination strives to create caring relations that bring together every earth being under a principle of equality and continuity (Cagüeñas, Galindo & Rasmussen 2020, 170). How is ecopolitical imagination being exercised in Bahía Málaga to secure piangua harvesting and the health of the mangrove ecosystem?

In 2019, women harvesters from Bahía Málaga created Asociación Raíces Piangüeras, whose aim is to “preserve and disseminate traditional knowledge around responsible piangua harvesting, and to protect the species and its habitat” (Raíces Piangüeras n.d.). The Association seeks to help them improve their family living conditions. Their desire is to become an example of territorial management and economic development for other communities facing similar challenges across the world. To achieve this, they have come up with four practices that enact their ecopolitical imagination: environmental conservation, traditional cuisine, communitarian governance, and expeditions for tourists (Raíces Piangüeras n.d.). This entry focuses on the first.

Key to their reparative and protective work is the piangüímetro. They use it to measure the shells’ size. In doing so, these women engage with another rhythm, that of the mollusc’s reproductive life (Vargas 2024). In workshops led by biologists and environmentalists, they have learned that pianguas smaller than 5 cm should not be collected, as they have not yet reached sexual maturity, i.e., they have not reproduced. To care for the mollusc’s wellbeing (that they now call their “black gold”), they have selected areas of the mangrove to plant young pianguas so that they can follow the cycle of life dictated by the tides.

Timing the harvest following the mollusc’s sex life is an expression of care and foresight; small pianguas are planted so that their offspring can prosper in their mangrove nursery. There is so much at stake at the 5 cm limit – the future of life as they know it, no less. Thus, they are strict. These women patiently measure each single harvested shell because future chance encounters depend on them. They make sure the times of piangua life are respected. Some things cannot be rushed when our common future is in peril. Profits ought not trump life: when life is at risk, “every human endeavour ceases to be important” (Krenak 2020, 10).

III.

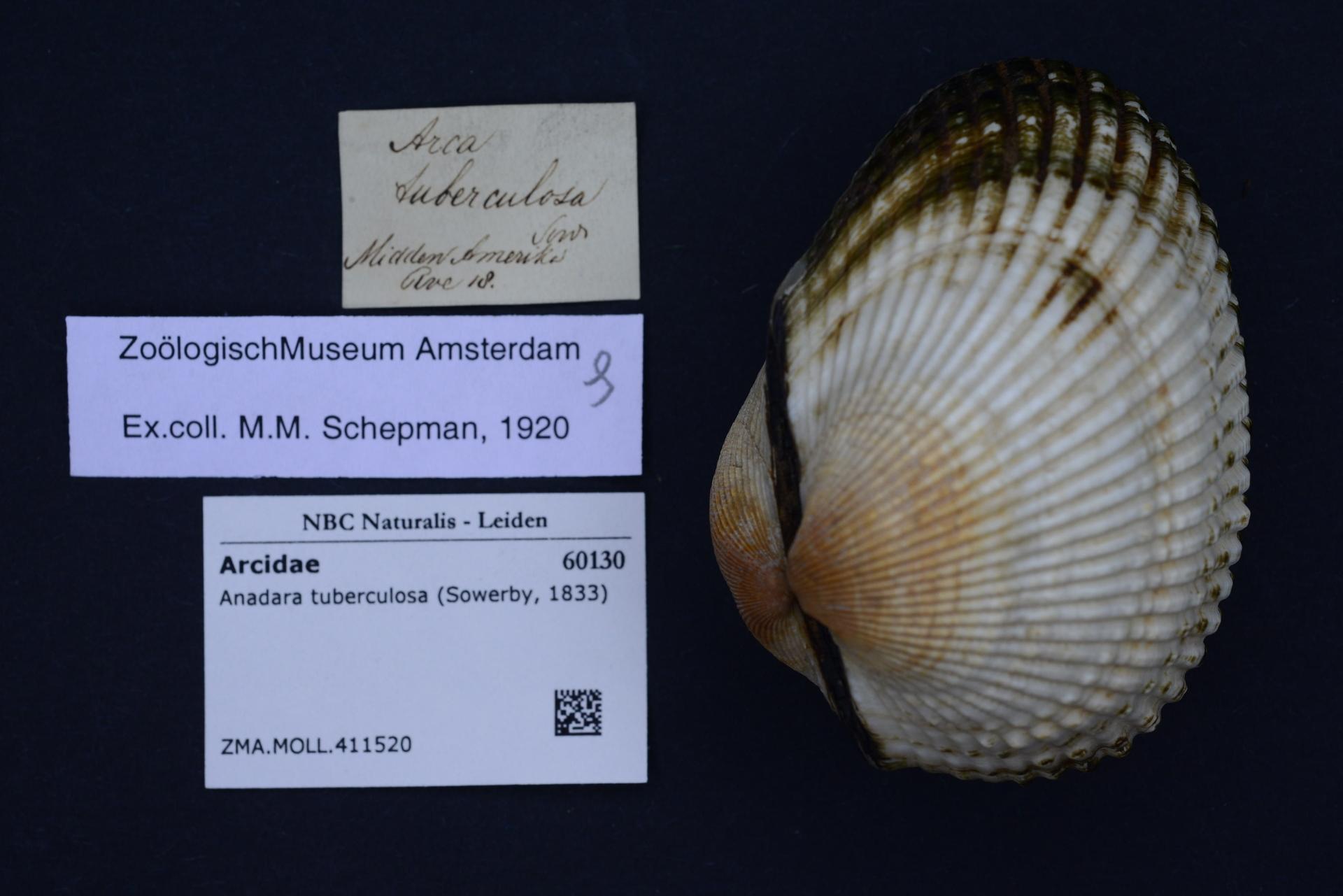

“Which engagements can we imagine dying for, or at least waging a war for?”, asks Isabelle Stengers (2018, 85). The women of Bahía Málaga have come together to nurture engagements that are certainly worth dying for. At the heart of their ecopolitical imagination lies anadara tuberculosa, common name mangrove cockle, a species of bivalve belonging to the family Arcidae (according to the taxonomical imagination so dear to the Western tradition, as pictured in Figure 2 below). Known as piangua on the Colombian Pacific coast, it has been a staple of local cuisine as far back as memory can reach. The mollusc has provided nourishment for Colombian black communities ever since they found refuge from the civil wars of the 19th century in the thickness of the rainforest.

Figure 2 [click to enlarge]. By Sowerby, 1833 - Naturalis Biodiversity Center, CC0. Source: Naturalis Biodiversity Center/Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2 [click to enlarge]. By Sowerby, 1833 - Naturalis Biodiversity Center, CC0. Source: Naturalis Biodiversity Center/Wikimedia Commons.

For centuries, in Bahía Malaga, life has flowed along the rhythm of strong and gentle tides. A month is divided into four tides: two pujas and two quiebras, each with their own high and low tides (Galindo Orrego 2019). The full moon summons the puja, a high and strong tide that pushes for a week the ocean water into the mangrove. When it recedes is the ideal time to harvest piangua. With the half-moon comes the quiebra, when the low tide does not recede as much as during puja. It is time to let pianguas rest. Such keen attention to tidal rhythms engenders a liquid ecology that does not think about water but with it. As Blackmore and Gómez claim, “liquidity and flow are not straightforward concepts that merely describe physical phenomena but instead tropes and metaphors loaded with histories and ideologies whose usage is never innocent” (2020, 2).

Women set sail on the first day of puja in search of the mollusc as the mangrove’s roots become exposed. This watery compass shapes daily life (Galindo Orrego 2021). It is hard work. Knee-deep in the mud, they bend over and sink their hands feeling for the mollusc’s shell, all the while hoping to avoid the painful sting of a toadfish that also makes the mangrove its home. Two dozen pianguas are enough for a stew; many more are needed to sell at Buenaventura, the nearest port and main town, if one wants to make a living out of piangua harvesting.

As the tide begins to rise again, they sail back home. This aquatic tempo guides the times of labour, care, and community: during puja, if the tide goes down at 6 in the morning, the boats can set sail at 9 a.m. and return in the afternoon, around 3 p.m., just in time to look after the household. During daylight, while men fish and hunt, women harvest piangua.

Or at least that is how it used to be. Times are changing. The political economy of piangua collecting and consumption has been disrupted since the purview of the Anthropocene (a misnomer for Capitalism) has reached Colombia’s Pacific Coast under the guise of large-scale fishing and logging, racist land grabbing and allegedly sustainable “ecotourism” (Grueso, Rosero and Escobar 2018). Something is amiss; piangua has become hard to find. Matilde Vergara Mosquera, a longtime piangüera, complains:

I remember how we used to cook piangua stew; my mom would make us a big pot, but now one can only glean some twelve dozen pianguas. It is no longer worth it; how can one eat some of it if there is nothing left to sell?

IV.

While the tidal rhythms of the Pacific Ocean remain largely unchanged, those of piangua harvesting have become less reliable. Piangua scarcity is a symptom of this disruption. Despite efforts at respecting the mollusc’s reproductive cycle, it is increasingly difficult to find pianguas over 5 cm. In the meantime, its retail price is rising as the mollusc has become a sought-after delicacy in restaurants across Colombia and Ecuador. However, most of the profit is split between middlemen and restaurant owners, while piangüeras are left with meagre profits (they are paid $0,6 per dozen). In addition, they face competition from outsiders (foráneos) who come to Bahía Málaga lusting after a piece of the bounty, without regard to shell sizes or resting periods.

According to a survey conducted by a team of biologists, an exploitation rate of 77%, plus low density and high mortality, suggests there is overexploitation of anadara tuberculosa in Bahía Málaga (Lucero, Cantera and Neira 2012). Synergies between local and scientific knowledge are central to the sustainability of mangroves and piangüeras (Sorge et al. 2025). Thus, all the bay’s four villages have engaged in ecopolitical imagination to counter capitalism’s destructive, endless appetite for profit. The Association is at the forefront of this struggle for the future of life: “for our communities, the mangrove represents the essence of life. It is our source of oxygen, our sustenance, our generator of development, and the pillar of our spirituality and everyday life” (Raíces Piangüeras n.d.). Which engagements can we imagine dying for? We cannot think of better ones.

V.

The labour that holds up the world is mostly due to women caring for others (Carrasco 2001; Comins 2015). Care does not look the same everywhere. Commitment to care for piangua, an earthly other, is not understandable regarding utilitarian ethics (I take care of the piangua and the mangrove because I need them, because they are of use to me). Conversely, “nonhuman others are not there to serve ‘us’. They are here to live with” (Puig de la Bellacasa 2010, 161). For the Afro-Colombian women of Bahía Málaga, care is resistance – it is a kind of ‘embodied knowledge’ built upon repeated observation and attentive walking through the mangrove guided by sound and scent.

By embodied knowledge, we mean “a conceptual tool to gain wisdom through an ability to feel, acknowledge and respond” (Cameron 2022, 29). As women harvesters refuse to indiscriminately collect the mollusc, they respond to the dominant, profit-driven logics of the extractivist mindset. Tidal rhythms and piangua’s slow reproductive maturation call for patient engagement. This is the challenge: how to resist the allure of fast profit when piangua is becoming as scarce as other sources of income? How not to get trapped into what Jason Moore calls “cheap nature,” i.e., “the ongoing, radically expansive, and relentlessly innovative quest to turn the work/energy of the biosphere into capital” (2015, 24)?

VI.

Piangua harvesting requires careful attention and nurturing responses. This caring disposition highlights multispecies entanglements “that are lured out of us through encounters with others” (Rose 2017, 58), thus helping us partake in the ceaseless creation of new life. In Bahía Málaga, this means designating nursing areas for young pianguas to grow undisturbed, carefully monitoring the mangrove to prevent illegal logging, feeding families, and helping children with their homework. Martha Liliana Salazar Ibargüen describes this hard work, this labour of love:

To harvest piangua, one needs lots of patience and love. Sometimes we arrive at a mangrove and someone else has already collected all of it. But as my mom says, ‘you have to smell the piangua.’ And I ask her, ‘Mom, how can you smell the piangua?’ And she tells me, ‘Yes, mija, it has its scent.’ I notice that men do not like this work as much – they are impatient; they do not want to dig here and there. That is why I say that piangua harvesting needs patience. The piangüera woman has an immense amount of it.

This embodied knowledge resists the urgency of modern, urban life. While capitalist relations demand speed, efficiency, and instant results, piangüeras engage in patient, attentive relations of mutuality. They offer a powerful alternative to the extractivist perspective that reduces non-human life to mere ‘resources,’ and instead practice relationships grounded on reciprocity, attentiveness, and connection (Krenak 2020). To this extent, the Association’s work exemplifies the potential of women-led, locally driven solutions in forest governance and care across species. Further, “their efforts provide valuable insights for developing more resilient and equitable approaches to forest management and conservation, blending traditional knowledge and community organisation with innovative and supportive policies” (Sorge et al., 9).

It is not our intention to idealise these practices of care. There is no harmonious communal existence between people and nature often imagined by outsiders. Life in Bahía Málaga is hard. Black communities along the Pacific coast have endured immense suffering: racist mistreatment, government neglect, drug trafficking violence, territorial militarisation, and harassment of grassroots movements (Quiceno 2016, Vergara-Figueroa 2018). And yet, they resist in every woman who chooses to keep on harvesting piangua in the respectful, patient ways taught by their elders.

VII.

Were we to embrace the Anthropocene narrative, we would have to accept two main tenets: (a) humans now wield a geological force (Chakrabarty 2009), and (b) humankind is the first geological force to become conscious of its geological role (Szerszynski 2012). Both tenets are contentious as they only make sense within the confines of Western thought and its understanding of history, ecology, and humanity. The ‘Anthropocene’ is part of a history of transgression, one in which humans usurp the realm of nature thanks to agriculture, colonialism, extractivism, petroculture, and the mastery of atomic energy (Moore 2015, Tsing 2012). We have become a reckless geological force. Or so the Anthropocene story goes.

There is a sense of urgency to this story. Mankind has disrupted the (re)production of life. It has gravely accelerated the greenhouse effect, tropical forest losses, and the acidification of the oceans. The voracious human appetite for energy in the age of capitalism is driving the planet to a point of no return. Extinction is our fate. An apocalyptic tone has been recently adopted in Western public discourse: “The end approaches, now there is no more time to tell the truth on the apocalypse” (Derrida 1984, 35).

To stop pondering on the truth of the end – such a dangerous temptation. An ecopolitical imagination ought not to abdicate when faced by the harbingers of doom, as they often hold “the ecofascist belief that environmental problems demand violent sacrifice of certain populations” (Anson 2022, 397). Extinction narratives are usually built on neo-Malthusian premises that naturalise scarcity, inequality, and conflict: “They problematically misdiagnose the causes of climate change, often placing blame on marginalised populations who have done little to cause the problem in the first place” (Ojeda, Sasser and Lunstrum 2020, 318). This can open the door for problematic population control measures, both coercive and militarised. On the contrary, we believe that “everywhere there is evidence of the nonviable and unacceptable modus of human life, and yet the one notion that is unacceptable […] is that human life has no value” (Colebrook 2014, 205).

Bahía Málaga’s liquid ecology teaches that human life has value indeed, insofar as it partakes of the universal mutual nurturing between lifeforms. At issue is the world to come. The women from the Association are adamant on this respect: “We want future generations to inherit this valuable mollusc that has guaranteed our families’ economic and gastronomic sustenance” (Raíces Piangüeras n.d.). Against the apocalyptic tone recently adopted in Western public discourse, we recall the words of the Brazilian indigenous writer and environmentalist Ailton Krenak: “We cannot surrender to the end-of-the-world narrative; it is meant to make us give up our dreams” (2019, 11).

VIII.

The piangüeras are having none of this apocalyptic gloom. They cannot miss the first day of puja, otherwise there will be neither piangua on the table nor income in the household. The age of capitalism has reached them, but not its ethics of doom and abdication. We intentionally use the term ‘age’ with capitalism. For if it is true that humankind has achieved ecological agency, then humans must come to terms with the realisation that the effects of their actions might go well beyond the limits of average human life expectancy or the existence of any given nation-state or Empire thus far. To the Western tradition, this posits unprecedented demands on how it has conceived of ethics, morality, and law. As the scope of human action reaches geological dimensions, so should the scope of responsibility (Malm and Hornborg 2014).

The people of Bahía Málaga have never lived as if their actions did not have effects far beyond their individual earthly lives. Their ecopolitical imagination is akin to the systems of “reciprocal relations and obligations”, whose virtue is to “teach us about living our lives with one another and the natural world in non-dominating and non-exploitative terms” (Coulthard 2014, 13). It is only through reciprocal relations and obligations that one can become attuned to the tidal rhythms that crystallise in the reproductive cycle of anadara tuberculosa and the earth beings that make a living with it.

Living in close engagement with the ups and downs of pujas and quiebras, to lunar cycles and molluscoid reproduction, gives the lie to the anthropocentric penchant of the Anthropocene story. Not only that, but it also gives the lie to its apocalyptic tone as the mutual nurturing of humans, pianguas, and mangroves is working against the disappearance of a livelihood that flows along the life cycle of an unassuming mollusc. Martha Liliana told us she dreams that the outside world knows “how we piangüeras feel, we want them to know that there is a small group of women who live and raise their children thanks to the piangua”.

IX.

In composing The Mediterranean, Braudel wanted to write a history in which the seasons – “a history of constant repetition, ever-recurring cycles” – and other recurrences in nature played an active role in moulding human actions. The history of “man’s relationship to the environment” was so slow as to be “almost timeless” (1972, 20). Braudel called this method longue durée and caused a stir in the headquarters of Western history departments. Meanwhile, this story had been told many times before. Dismissed as ‘myths’ or “geomythologies” (Vitaliano 1968), many nonwestern cosmologies have known all too well the long periods that comprise earthly life and the ethical demands that such ancestry lays on every single living being. Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa, for instance, likes to remember that “far from the forest, there are many other peoples than ours. Yet none of them possess a name similar to ours. This is why we must continue to live on the land that Omama left us in the beginning of time” (2013, 25).

Afro-Colombian communities also look back to their ancestors in search of protection and wisdom against present violence, poverty, and dispossession. They establish a moral continuity with ancestral time in a way that acknowledges the agency of nonhuman actors in the political realm (Quiceno 2016, 140). Mutual, caring relations between piangüeras and pianguas are not an expression of local mythologies, customs, or folklore. They are, rather, enactments of an ecopolitical imagination deeply attuned to the tidal rhythms of a liquid ecology that has sustained mangrove earth beings for centuries. As such, this age-old, embodied knowledge, inherited through daily multispecies engagements and a deep respect for ancestry, is a thoroughly contemporary political wager on future conviviality.

Contemporary liberal discourse wants us to believe that green capitalism and sustainable consumption might lead us back to ‘nature.’ That is the myth we must resist. We have never left ‘nature’ behind. We have always already been part of tidal rhythms that orchestrate the proper time for living and dying, irrespective of the illusory benefits of predatory capital. There is no end of the world for those who make the world come alive day to day.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the women of Asociación Raíces Piangüeras for welcoming us into the ways and byways of the piangua. Special thanks to Martha Liliana Salazar Ibargüen for her patience with our many questions. We would like to recognise Matilde Mosquera Murillo for her leadership and daily commitment to the Association. Fieldwork was partly funded by Universidad Icesi, Cali, Colombia.

This essay is dedicated to the memory of María Isabel Galindo Orrego, a true telluric force.

References

Anson, April. 2022. “‘Ghastly Whiteness’: Ecofascism and Indigenous Ecofeminism on Cogewea’s Frontier.” In The Routledge Companion to Gender and the American West, edited by Susan Bernandin, 397-409. London: Routledge.

Blackmore, Lisa and Liliana Gómez. 2020. “Beyond the Blue: Notes on the Liquid Turn.” In Liquid Ecologies in Latin American and Caribbean Art, edited by Lisa Blackmore and Liliana Gómez, 1-10. London: Routledge.

Braudel, Fernand. 1972. The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Volume I. New York: Collins.

Cagüeñas, Diego, María Isabel Galindo Orrego, and Sabina Rasmussen. 2020. “El Atrato y sus guardianes: imaginación ecopolítica para hilar nuevos derechos.” Revista Colombiana de Antropología 56 (2): 169-96.

Cameron, Liz. 2022. “Indigenous Ecological Knowledge Systems: Exploring Sensory Narratives.” Ecological Management & Restoration 23 (S1): 27-32.

Carrasco, Cristina. 2001. “La sostenibilidad de la vida humana: ¿Un asunto de mujeres?” Mientras Tanto 82: 43-70.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2008. “The Climate of History: Four Theses.” Critical Inquiry 35 (2): 197-222.

Colebrook, Claire. 2014. Death of the PostHuman: Essays on Extinction, Vol. 1. Open Humanities Press.

Comins, Irene. 2015. “La ética del cuidado en sociedades globalizadas: hacia una ciudadanía cosmopolita.” Themata 52: 159-78.

Coulthard, Glen Sean. 2014. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Cruz Hernández, Delmy Tania. 2020. “Mujeres, cuerpo y territorios: entre la defensa y la desposesión.” In Cuerpos, territorios y feminismos: compilación latinoamericana de teorías, metodologías y prácticas políticas, edited by Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo, 45-62. Quito: Abya Yala.

Derrida, Jacques. 1984. “Of an Apocalyptic Tone Recently Adopted in Philosophy.” Oxford Literary Review 6 (2): 3-37.

Galindo Orrego, María Isabel. 2019. “Viviendo con el mar: inestabilidad litoral y territorios en movimiento en La Barra, Pacífico colombiano.” Revista Colombiana de Antropología 55 (1): 29-57.

Galindo Orrego, María Isabel. 2021. “La vida orillera: agitaciones violentas y arremetidas del mar en el Pacífico colombiano.” Revista de Antropología y Sociología: Virajes 23 (2): 59-78.

Gómez-Barris, Macarena. 2017. The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives. Durham: Duke University Press.

González, Axel. 2019. “Racial Capitalism and Nature.” American Quarterly 71 (4): 1155-67.

Grueso, Libia, Carlos Rosero, and Arturo Escobar. 2018. “The Process of Black Community Organization in the Southern Pacific Coast Region of Colombia.” In Cultures of Politics, Politics of Cultures: Revisioning Latin American Social Movements, edited by Sonia Álvarez, Evelina Dagnino, and Arturo Escobar, 196-219. New York: Routledge.

Kopenawa, Davi and Bruce Albert. 2013. The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

Krenak, Ailton. 2019. Ideas para postergar el fin del mundo. São Paulo: Colectivo Siesta.

Krenak, Ailton. 2020. O amanhã não está à venda. São Paulo: Companhia Das Letras.

Lucero, Carlos, Jaime Cantera, and Raúl Neira. 2012. “Pesquería y crecimiento de la piangua (Arcoida: Arcidae) Anadara tuberculosa en la Bahía de Málaga del Pacífico colombiano, 2005-2007.” Revista de Biología Tropical 60 (1): 203-17.

Malm, Andreas and Alf Hornborg. 2014. “The Geology of Mankind? A Critique of the Anthropocene Narrative.” The Anthropocene Review 1 (1): 62-9.

Moore, Jason. 2015. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. New York: Verso.

Ojeda, Diana, Jade S. Sasser, and Elizabeth Lunstrum. 2020. “Malthus’s Specter and the Anthropocene.” Gender, Place & Culture 27 (3): 316-32.

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. 2010. “Ethical Doings in Naturecultures.” Ethics, Place & Environment 13 (2): 151-69.

Quiceno, Natalia. 2016. Vivir sabroso: luchas y movimientos afroatrateños en Bojayá, Chocó, Colombia. Bogotá: Editorial Universidad del Rosario.

Raíces Piangüeras. N.d. “Quiénes somos.” Accessed May 23, 2025. https://raicespiangueras.com/qui%C3%A9nes-somos

Rose, Deborah Bird. 2017. “Shimmer: When All You Love Is Being Thrashed.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan and Nils Bubandt, 51-63. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Sorge, Stefan, Natalia Zapata, Camilo Romero et al. 2025. “Piangüeras: Guardians of the Mangrove in the Colombian Pacific.” Tropical Forest Issues 63: 3-10.

Stengers, Isabelle. 2018. “The Challenge of Ontological Politics.” In A World of Many Worlds, edited by Marisol de la Cadena and Mario Blaser, 83-111. Durham: Duke University Press.

Szerszynski, Bronislaw. 2012. “The End of the End of Nature: The Anthropocene and the Fate of the Human.” Oxford Literary Review 34 (2): 165-84.

Tsing, Anna. 2012. “Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species.” Environmental Humanities 1: 141-54.

Vargas, Laura Isabel. 2024. “El ritmo de la incertidumbre: pianguas menguantes. Organización en torno a una vida no-humana.” BA tesis. Universidad Icesi.

Vergara-Figueroa, Aurora. 2018. Afrodescendant Resistance to Deracination in Colombia: Massacre at Bellavista–Bojayá–Chocó. New York: Palgrave.

Vitaliano, Dorothy. 1968. “Geomythology: The Impact of Geologic Events on History and Legend with Special Reference to Atlantis.” Journal of the Folklore Institute 5 (1): 5-30.