Solar Geoengineering

Ala Roushan

Our entanglement with the Sun is tethered to ancient traditions of Sun worship. While these practices were preoccupied with cosmic order, they were often rooted in the desire to control the natural world – emerging at times in response to environmental uncertainties and climatic changes. Confronted with today’s climate crises, we find that impulse in proposals for solar geoengineering: technologies that seek to mediate the Sun by artificially reconditioning the atmosphere. Under the umbrella of solar geoengineering, strategies such as stratospheric aerosol scattering are being developed to reflect a small percentage of solar rays, to help temper global warming (Salata Institute n.d.).

Tracing a longstanding history, one of humanity’s earliest negotiations with the Sun can be found in the ancient Iranian Mitra cult, whose rituals sought to harmonize celestial forces (Nabaraz 1999). In mapping this arc, a most intriguing correlation appears: the forging of the deity Mitra aligns with a planetary climate change around 4,200 years ago (Gramling 2018). This early veneration of Mitra predates the Indo-Iranian divergence into the separate cultural streams of Vedic and Zoroastrian cultures, and lies thousands of years before the Roman appropriation known as Mithraism. Fortunately, even with sparse archaeological evidence and no surviving writings, comparative linguistics between the Indo-Aryan and Iranian branches provides insights into their shared ancestral culture, illuminating the belief systems of this distant past.

The earliest written references to Mithra/Mitra appear in the Iranian Avesta and the Indian Vedas, both preserving traces of their proto-Indo-Iranian origins. Since the cultural split occurred more than 4,000 years ago, the shared presence of Mitra strongly suggests that worship of this deity predates the separation: “In that unknown epoch when the ancestors of the Persians were still united with those of the Hindus, they were already worshippers of Mithra.” (Cumont 1903, 3). As an oral culture, this era remains shrouded in mystery with layers of revisionist narratives. Yet, one thread endures: the deity Mitra radiating as a divine light, guiding the Sun in a sacred accord.

By further correlating recent geological and archaeological findings, evidence from this epoch suggests a period of aridification and prolonged drought, triggering both climatic disruption and political upheaval (Marshall 2022). During that era, it was commonly believed that terrestrial events such as droughts, floods, and plagues were influenced by celestial drama. As scholar Roger Beck describes, “Mithraism was an astral religion. The perceivable heavens and the celestial bodies (sun, moon, the other five planets, stars) all played a part in the mysteries – the sun necessarily a very large part, since Mithras himself was the Sun god.” (Beck 2020) And so, the hardship brought on by environmental change may well have been understood as a divine reckoning imposed by the Sun.

In the limited iconography that survives, Mitra is depicted triumphant, adorned with rays of light and often carrying the Sun in his chariot. This iconography reflects a widespread belief in Mitra’s influence over solar power – a conviction that drove followers to expand territories, cultivate landscapes, and support the growth of their civilization. Such reverence for solar power propelled the rise of the Persian Empire, the largest empire the world had yet seen. Here, we encounter a recurring pattern that philosopher Georges Bataille describes as “solar economy” – a system that, across millennia, channels the overabundance of solar energy into cycles of growth and expansion. As Bataille observes, “if the system can no longer grow, or if the excess cannot be completely absorbed in its growth, it must necessarily be lost without profit; it must be spent, willingly or not, gloriously or catastrophically.” (Bataille 1988, 21).

From the Egyptians to the Mayans, ancient Iranians participated in a long-standing lineage of solar cults and solar empires that continues into the present epoch of the Anthropocene. Today, we live with the fallout of that legacy: a profound climate crisis shaped by heat-trapping gases and a destabilized atmosphere. There is no doubt that our climate crisis today is a consequence of our own actions – centuries of extractive economies and imperial expansion. Faced with this existential predicament, we once again turn to the sky, much like the ancient followers of Mitra, seeking extraordinary interventions. But this time, our hope is not sustained by the past deities we engineered. Instead, our rituals appeal to planetary-scale technologies to manage, manipulate, and reshape the atmosphere: technologies such as solar geoengineering, also referred to as solar radiation management (Keith 2013).

Solar geoengineering proposes various protocols to create planetary sun shields to help reduce global temperatures. One strategy involves injecting reflective aerosols into the stratosphere, with chemical options including sulfate aerosols, diamond dust, calcium carbonate, and silica aerogels. However, serious concerns have prompted initiatives for a global moratorium and the establishment of non-use agreements due to fears of unforeseen consequences on the biosphere and cascading environmental disruptions. These include weather pattern domino effects that destabilize regional rainfall patterns, monsoons, and ocean currents (Kolbert 2021). Additionally, there is the apprehension that even if the strategy is successful, temperatures will rebound to even greater numbers upon cessation of operation – an ecological return of the repressed.

The main obstacles and source of strong resistance to this strategy rests on what seems are two insurmountable domains: first, achieving the science for accurate and effective implementation, which includes addressing discrepancies between predictive models and sustainable real-world outcomes to avoid unforeseeable catastrophes; and second, the political difficulty of establishing adequate governance, which demands securing a long-term global consensus (Buck 2019). In the face of extreme climate conditions and the threat of temperatures fatal to human life (among other forms of threatened life), these dystopian technologies are becoming solutions of last resort – a future that is fast approaching. Yet, with constraints on real-world experimentation, solar geoengineering currently relies almost entirely on computational modeling to simulate the complexities of Earth’s climate dynamics and weather patterns. This reliance exposes us to epistemic blind spots, thus raising fundamental questions: Can these computational models truly anticipate the ripple effects of atmospheric intervention? And even if they could, can those models form the basis for cohesive governance on a planetary scale?

Echoing the belief system of the ancient Mitra cult, which shaped early human relationships to the environment, today’s polemics around solar geoengineering reveal a recurring pattern: the human inclination to be governed by constructed ideologies. Our present moment is marked by a troubling regression in public discourse, where climate denial accelerates the catastrophe unfolding before us. In contrast, we also see the rise of techno-optimism or techno-solutionism (Morozov 2013) – a belief that acknowledges the crisis but places unwavering faith in technological solutions. This perspective often overlooks the grave risks of relying on shortcuts that avoid reducing consumption, dismantling extractive systems, and confronting the structural roots of climate collapse. At the opposite pole are those who idealize nature, imagining a return to a pure, pre-technological world as the only viable path forward. Yet this reactionary stance resists critical research, with protests resulting in the cancellation of real-world testing and a push for the defunding of geoengineering studies (Temple 2024). These polarized ideologies – denialism, techno-solutionism, and naïve pastoral views of nature – continue along the same trajectories that have led us here. Such ideologies extend beyond our imagination of the world, inscribing themselves into the material realities that shape our environment.

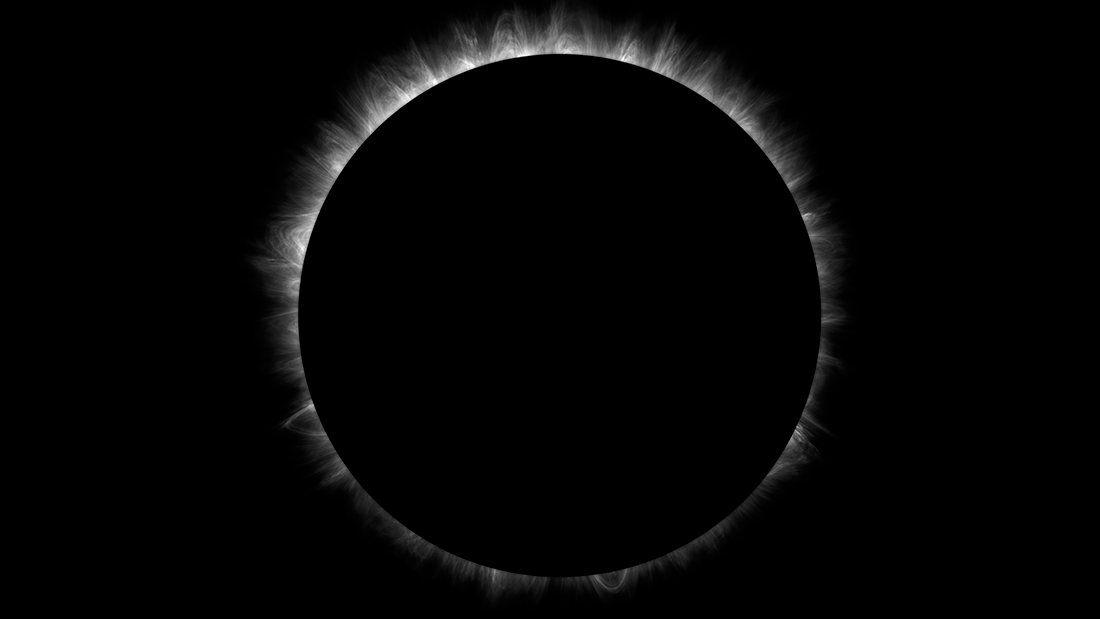

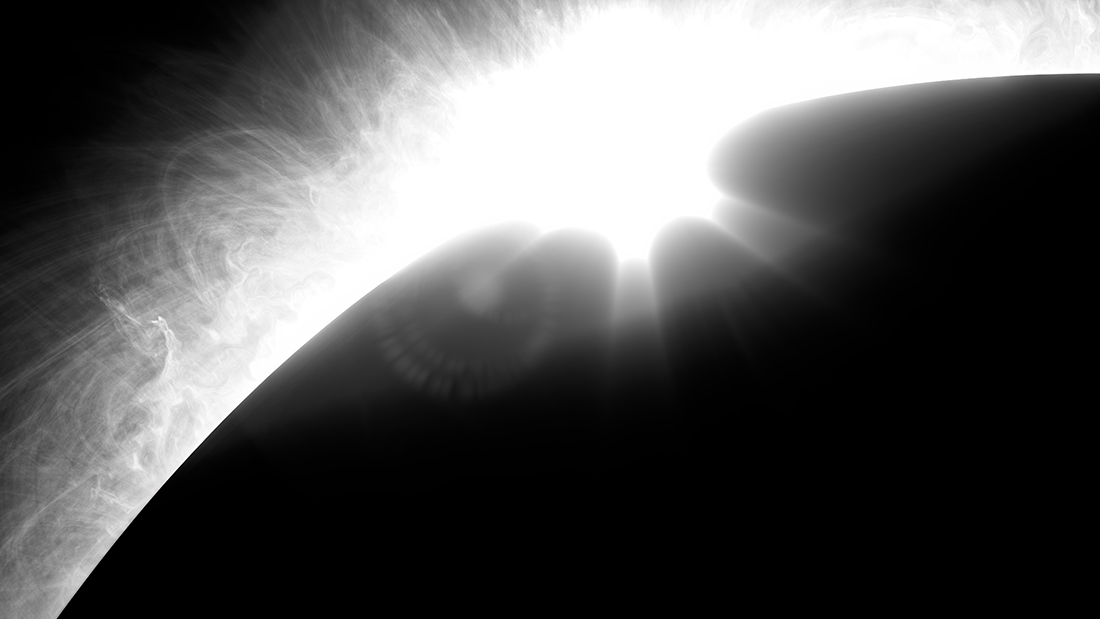

A Shroud Woven of Solar Threads is an immersive video that connects the ancient Iranian Sun worship of Mitra – which coincided with the climate crises 4200 years ago – with the contemporary concept of solar geoengineering. Combining 3D scans of the oldest surviving Mitra temple, a speculative model of Proto-Indo-Iranian (reconstructed using an LLM), and a gravitational model of the Sun, the entire film's world is a hyperrealistic model, underlining the position that we can only engage "Nature" as a modelled simulation to intervene in its process. Revolving around a subterranean ritual, the surface of the cavernous temple eventually disintegrates into a particle cloud as the ancient language morphs into a futuristic computer script suggesting a protocol for solar geoengineering. The soundtrack is generated exclusively from period sounds by modulating and synthesizing fire, human voice, solar radiation recordings, and the ancient ney instrument.

References

Bataille, Georges. 1988. The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy. Vol. 1: Consumption. New York: Zone Books.

Beck, Roger. 2020. “Mithraism” Encyclopaedia Iranica. Leiden: Brill.

Buck, Holly Jean. 2019. After Geoengineering: Climate Tragedy, Repair, and Restoration. Verso Books.

Cumont, Franz. 1903. The Mysteries of Mithra. Chicago: Open Court Publishing.

Gramling, Carolyn. 2018. “Massive Drought or Myth? Scientists Spar over an Ancient Climate Event behind Our New Geological Age.” Science (April 6, 2018).

Kolbert, Elizabeth. 2021. Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future. New York: Crown.

Keith, David. 2013. A Case for Climate Engineering. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Marshall, Michael. 2022. “Did a Mega Drought Topple Empires 4,200 Years Ago?” Nature 601 (7894): 498-501.

Morozov, Evgeny. 2013. To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York: PublicAffairs.

Nabaraz, Payam. 1999. Iranian Religions & Beliefs: Mithras and Mithraism. Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies, SOAS University of London.

Salata Institute (The Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability at Harvard University). n.d. “The Harvard Solar Geoengineering Research Program (SGRP)”.

Temple, James. 2024. Harvard has halted its long-planned atmospheric geoengineering experiment. MIT Technology Review.