Social Landart

Insa Winkler

Key terms: collective art, ethnography, mutual learning, nature-human relationship, place, social sculpture, spatial intervention, transdisciplinarity

1. Introduction

This article explores the question of which artistic and scientific approaches characterize “Social Landart”. Examples of projects are used to outline the criteria of Social Landart practice in its intention to promote awareness of the future and sustainability. The analysis follows from the perspective of my own artistic practice. The term “Social Landart” emerged from a series of collective art interventions related to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. These projects were part of the artistic initiative “Intervention Rowkowitschi” and took place in the contaminated zone of Belarus. The projects were featured in several exhibitions under the title “Reflexion Chernobyl” (Winkler 1998). Social Landart then evolved into artistic research on agricultural crises such as the BSE (Bovine spongiform encephalopathy) epidemic, as well as animal husbandry in general (Winkler 2020). Social Landart sees itself as a concept of art in relation to the environment and nature, as well as to society and ecology, and their relevant conditions and responsibilities. The paper consists of two parts: firstly, the relation between “Social Sculpture” and “Social Landart” and, secondly, the implementation requirements, prerequisites, and practical characteristics of the realization of Social Landart praxis in general.

2. Genesis of Social Landart

In the related fields of Social Sculpture and Social Landart, a central motivation is to bolster social creativity for transformational processes. The underlying idea is that individuals can shape themselves and their collective living space, particularly in collaboration with others. However, both approaches also emphasize the challenge of implementing ideas as concrete experimental trials in real situations and spaces. They face the challenge of linking current issues with visions of the future and exploring how reflections can be used to develop accessible, manageable narratives as practical examples, as well as to enable their communication in public spaces.

“Social Landart” is based on Joseph Beuys’ concept of “social sculpture”. His project “7000 Oaks” (Documenta 7, Kassel, 1982), which can be regarded as his most enduring social sculpture, is also a perfect example of a successful “Social Landart” project. Beuys presented a large pile of 7000 basalt stones, which were gradually placed one by one next to 7000 planted oak trees and gradually shaped the urban area of Kassel over several decades, demonstrating the leverage that art can have (Stiftung “7000 Eichen” 2022): The entire Documenta administration and the residents are still part of a “living social organism,” as Beuys called it in his concept. His “basic idea of renewing the social whole” leads him to the concept of “Social Sculpture” (Beuys 2006). “7000 Oaks” is very representative of the opportunities that art-based interventions can provide: a participatory practice that has led to ecological and social urban development. It also demonstrates that ecological and art-based experiments or interventions can evolve successively.

Today, the concept of Social Sculpture is still closely linked to Joseph Beuys’s idea of “Gesamtkunstwerk,” which he manifested, along with the social sculpture concept, in the context of the “Free International University” (FIU). It lives on in the form of the “Social Sculpture Research Unit” at Oxford Brookes University (1998), which today aims to safeguard and pass on the theories and practices of social sculpture. The core ideas of Beuys are being kept alive and developed further in a “Global Social Sculpture Lab”, through the methods of “connecting practice” and “awareness-raising instruments”, particularly thanks to the initiative of Beuys’ student and artist Shelley Sacks (Sacks 2021).

Land Art, originally called “Earthworks”, emerged in the 1960s from artists’ desire to break free from the confines of the museum and use the great outdoors as a studio, regardless of human influences. Such landscape works took place in the vast American territories. The term Earthworks was coined in the “no man’s land” of America, and it quickly became known as “Land Art” in Germany. Here, such works occurred more frequently in densely populated areas and in the context of land use, which is essentially already associated with agriculture or urbanization.

Art deals with the habitat of an environment, characterized by certain visible strengths and boundaries of nature and people. In this prospect, Social Landart is linked to methods of rural and land use, shared urban space, and transformative qualities of common ground. In this perspective, Social Landart is “artistic-research”-oriented, for example, when projects are developed through “Sensory Ethnography” using sensory exploration methods (Pink 2013, 16).

The concept of Social Landart is based on the experience and character of concrete artistic interventions, such as the ones I have initiated and carried out myself, for example, the “Acorn Pig” project (1999–2012), which was about an alternative to factory farming, a practice that depends on oak trees. Such an art project is designed for the long term to achieve a result (transformation). In this case, Social Landart works transdisciplinarily (Nicolescu 2002) and can be comprehensible and worthy of imitation or even feasible for agriculture (here, the artist had also entered into the practice of Acorn pig-feeding).

Video documentation of the “Acorn Pig” project (199–2012) by Insa Winkler.

Another example is a “(Bio)diversity corridor” (2016–2019), a project by the German artist collective artecology_network in collaboration with the sustainability sciences at Leuphana University of Lüneburg. It conveyed the dimensions of diversity in rural areas as an imaginary and concrete scope, whereby joint learning in the various administrative departments was organized through art to bring the “common corridor” to life and create new approaches to diversity. Comparable artistic projects include, for example, the individual determination of “favorite places” by Werner Henkel, the marking of “Civil Wilderness” by Helene von Oldenburg and Claudia Reiche, or the conscious use of “Beloved neophytes” in the cultural landscape by Anja Schoeller (Leuphana University of Lüneburg and artecology_network 2018).

Another example is the artistic work in a contaminated area in Belarus, where art becomes the voice of a population suffering from humanitarian grievances, like the situation after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. In the project “Reflexion Chernobyl” (1996–1998), we offered communication tools and performed with a local school in a contaminated village. Ultimately, this was a form of participatory art in collaboration with the political opposition to the government, which made the hidden circumstances of the atomic legacy transparent.

Issues such as the destruction of nature, i.e., the loss of biodiversity, environmental pollution, desertification, and the exploitation of resources are examples of a fundamental “crisis”, the examination of which characterizes the discourse of Social Landart. Starting from humans, the environment opens up an infinite field of problems dedicated to each spot and demands other possibilities that rethink and reshape the substance of culture and creation. It is therefore obvious that Social Landart works empirically in and around real habitats and thus always includes its living beings in such a space with all human influences on the land. Art develops out of this living space and is less a predetermined concept that is imposed on an area. Of course, the idea of a new or another land is also all about a concept that emerges first as a desire of the mind and a need. It encompasses both the positive and the negative approaches to shaping the world, seen as the continuous development of our general world cultural heritage, to say that if humans are artists, then what they create is also art. In comparison to Land Art, however, Social Landart is more independent of material. Artistic visibility is also the presence of the performer in a social landscape. Ideally, a collective intrinsic impulse is created that becomes tangible in temporary actions. Art can have different aspects. It can be immaterial, performative, conceptual, or applied. Temporarily visible works are not excluded. Art can be a catalyst for change.

3. Criteria and practice of Social Landart

So how can Social Landart practice convey comprehensible criteria?

It has already been mentioned that Social Landart is oriented towards ephemeral artistic methods and includes a variety of interventionist and actionist practices such as performance and happenings. But it also means that the artist is just as involved in “non-artistic actions”, e.g., when the “Acorn Pig” project demands that the artist practices sound and responsible animal husbandry, including even ham production. At the same time, they promote the transformation process within an artistic happening: The ten pigs, which were part of the alternative free-range pig farming project, were also trained as racing pigs. This illustrated the intelligent abilities of the species. The temporary agricultural laboratory artistically exaggerated these experiences with a public “Acorn Pig Race” performance. In contrast to the predominantly invisible fattening of animals, this reveals the intelligence and willingness of 'normal' pigs that cooperate with humans, thereby raising cognitive dissonance among meat consumers. In such a “holistic” way, art reaches the limits of its own societal job description and challenges other disciplines to think outside the box

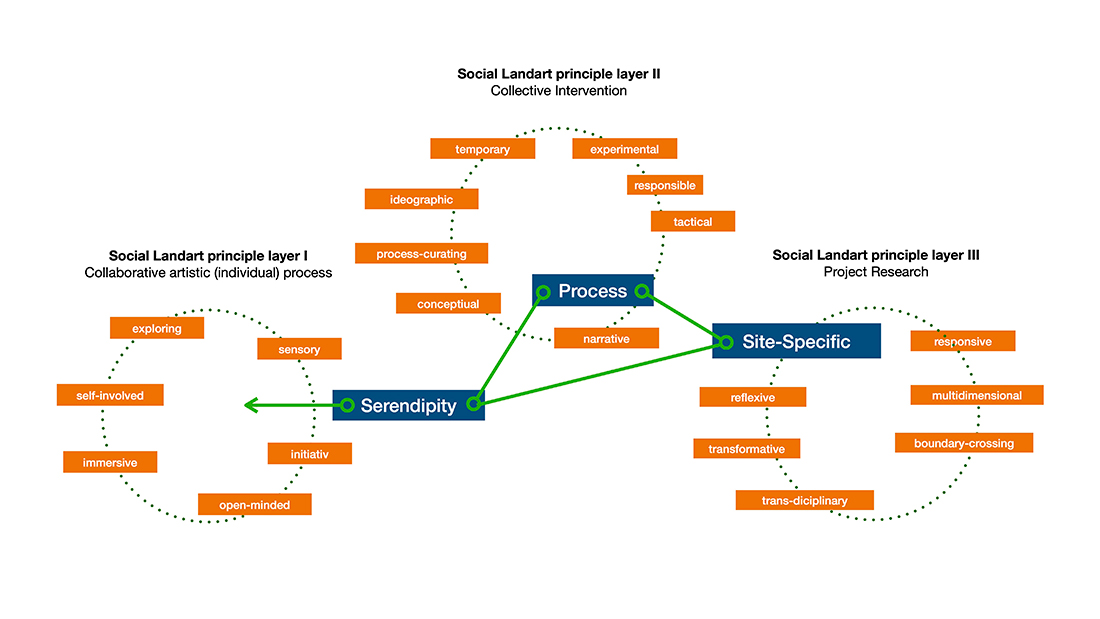

Since the topics and areas, as well as the protagonists and implementation strategies of Social Landart, are unique and therefore always different, I will limit myself here to an overview of general project phases and their prerequisites. There is the usual triad of concept phase, development phase, and results phase in a Social Landart project. Realization requirements (applications, commissions) for specific areas and themes demand a more complex approach. Artists follow useful coincidences and take advantage of this serendipity (Kagan 2012). This is where the artistic intervention differs from the scientific case study: The collegial artistic and scientific collaborations on site, often bottom-up, show an individual research process which feeds the site- and topic-specific collective intervention in a unique and socially connected approach. An artistic research project thus does not support hypotheses, but follows the traces of existing – but not obvious – phenomena for change through a special strategy (see fig. 1). Attributes such as “eager to discover”, “self-involving”, “immersive”, “open-minded”, “proactive”, or “sensual,” which also describe general attitudes of creative industries, are fundamental characteristics of artistic research.

To make social transformation visible, further criteria are required to proceed conceptually in the sense of Social Landart. Both the initiators, whether invitation-based or self-commissioned, engage in an open-ended process in which an unbiased search for undiscovered possibilities, the uncovering of problems, and the formulation of individual and joint questions allow for the basic idea of a concept. To develop a joint, location- or topic-specific project that is comprehensible to the public and at the same time implemented in a process-oriented and participatory manner, a common motto or motif is required. In the “Acorn Pig” project, for example, a pig with wings made of oak leaves symbolizes free-range pigs in search of acorns. A common research question: “What can a ' Bio-Diversity Corridor' mean or look like?” encourages responsible, tactical collaboration, especially when sensitive issues and critical narratives are addressed in researching an area or topic. Here, artists develop ideographic methods to accommodate the experimental nature of art and identify narratives that informally support the empirical process. Art can help to identify existing key issues and overcome the status quo.

4. Conclusions

The discussion of crisis and challenge in a chosen space has the potential to act as a catalyst for artistic research, inspiring the rendering of such a space legible or enabling it to be experienced as changeable. There can be no improvement of a theme or subject matter without a certain crisis. The central questions that arise about the collective challenge require interdisciplinary solutions and form the basis for collaborative projects with political, scientific, and public entities that employ artistic methods.

In summary, Social Landart explores innovative themes that challenge anthropocentric perspectives relating to landscapes, land, and people. The endeavor to effect change in creative and immersive ways with foresight is directly linked to artistic interventions that target these leverage points. Thus, social land art is both self-inspired and animistic.

A site-specific, collective art project involves the interaction between the participants in a project and an area, as well as the reaction to the environment or nature, and it raises a specific question bound to this area. The success of a Social Landart project, which is usually complex, provokes substantial, system-recognizing results that enable cross-border reflection on the area as a place or topic. The approaches are transdisciplinary and involve stakeholders from the project area, ideally already making transformative results visible in the process. The artistic sub-projects and interdisciplinary collaborations are responsive and dialogue-based. Such a multidimensional project level allows for accompanying studies and external observations and takes place in an open time frame.

Social Landart is important for two reasons. Firstly, it is used as a way of doing artistic research in long-term projects and interventions. Secondly, it is used to teach people (in workshops, etc.) to be more artistic and empathic. When teaching about the environment, it is important to show and experience sensitive perception methods in nature and landscape. This can help us understand why art that focuses on the environment is important for protecting the planet. This is especially clear when looking at the mix of Social Sculpture, which is all about personal growth, and Social Landart, which is mostly about working together to enable wider changes.

References

Nicolescu, Basarab. 2002. Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity. New York SUNY Press.

Beuys. Joseph. 2006 [1986]. Mein Dank an Lehmbruck. Eine Rede. Munich: Schirmer/Mosel.

Kagan, Sacha. 2012. “Toward Global (Environ)Mental Change. Transformative Art and Cultures of Sustainability,” edited by Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

Leuphana Universität Lüneburg and artecology_network. 2018. “(Bio-)Diversitätskorrdior. Natur und Mensch im Landkreis Oldenburg. Leverage Points for Sustainability Transformation. Case study in the district of Oldenburg. Lower Saxony.”

Oxford Brookes University. 1998. “Social Sculpture Research Unit”.

Pink, Sarah. 2013. Doing Sensory Ethnography. Principles For Sensory Ethnography: Perception, Place, Knowing, Memory and Imagination. London: Sage.

Sacks. Shelley. 2021. “Global Social Social Sculpture Lab”.

Stiftung “7000 Eichen“. 2022. “Joseph Beuys: ‘7000 Eichen,’ Documenta 7. Kassel 1982”.

Vilsmaier, Ulli. 2018. “Grenzarbeit in integrativer und grenzüberschreitender Forschung.“ In Grenzen: Theoretische, konzeptionelle und praxisbezogene Fragestellungen zu Grenzen und deren Überschreitungen, Hrsg. von Martin Heitel und Robert Musil. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Winkler, Insa. 1998. Reflexion Tschernobyl. Dokumentation der Intervention in der Tschernobylzone. Amsterdam: Jaap van Triest.

Winkler, Insa. 2020. Social Landart – (Land-)Wirtschaft und Kunst. Wie ein Eichelschwein zwischen künstlerischer Forschung und Nachhaltigkeitswissenschaft vermittelt. Munich: Oekom.