Retreat

Ole Fryd

Related terms: managed realignment, planned relocation, climate gentrification, land swap, buyout

Should I stay or should I go? If I go, there will be trouble. If I stay, it will be double.

The English punk rock band The Clash (1982) were clear about this critical dilemma in relationships, which is also applicable to climate adaptation policy and planning. Should frequently flooded houses be reconstructed at all costs? Should a settlement ridden by wildfires be rebuilt at the same site? Would the decision to stay be an ethically viable option? Would the decision to go sacrifice the intricate relationship between human habitation and the natural environment?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) refers to three main response strategies to mitigate the impacts of environmental hazards on human settlements. That is, protection, accommodation, and retreat. Protection is ‘to stay’ and construct physical barriers that aim to protect human populations against hazards, e.g. by building flood walls. Accommodation is to stay and learn to live with the risk of disasters. This includes preparedness, building up resilience in communities, and an ability to ‘build-back-better’ in the aftermath of a disaster. An example of this is the multifaceted earthquake risk reduction efforts in Japan. Retreat is the decision not to stay, but ‘to go.’ It is not to fight the forces of nature or learning to live with the risk of disasters, but, more humbly, to (let) go and phase out human habitation and intensive land uses in hazard areas.

Among the three main strategies proposed by the IPCC, retreat is the least commonly applied response option in practice. The reasons for this can be many, including cultural and cognitive human traits. This calls for critical analysis, reflection and potential redefinitions of retreat – also from an environmental humanities perspective. This entry aims to initiate and inform this discussion by nuancing the means, ends, and dilemmas associated with retreat as an environmental planning option.

Defining retreat

According to Britannica, Cambridge Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, and the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘retreat’ is commonly referred to as:

- The process of moving away, e.g. retreating glaciers

- The act of escaping from a dangerous situation, e.g. retreating troops

- The decision to change an opinion, e.g. retreating from an original position, or

- The description of a quiet and private place, e.g. a spiritual retreat.

In climate adaptation policy, ‘retreat’ is defined as the movement of people and assets out of harm’s way. It is the extensification of intensive land use in hazard areas. This is a somewhat narrow definition that can be expanded to release the wider potential of ‘retreat’ as a conceptual outset. When human habitation is confronted by the superior forces of nature, catalysed by human-induced climate change, retreat arguably becomes inevitable, and it provides new pathways for multispecies and intergenerational justice. Hence, retreat is also about revisiting an assumed hierarchy of species and prioritising long-term environmental benefits over short-term human costs.

The specific use of retreat in urban planning and climate adaptation policy

As a policy and planning measure, retreat can be subdivided into four categories.

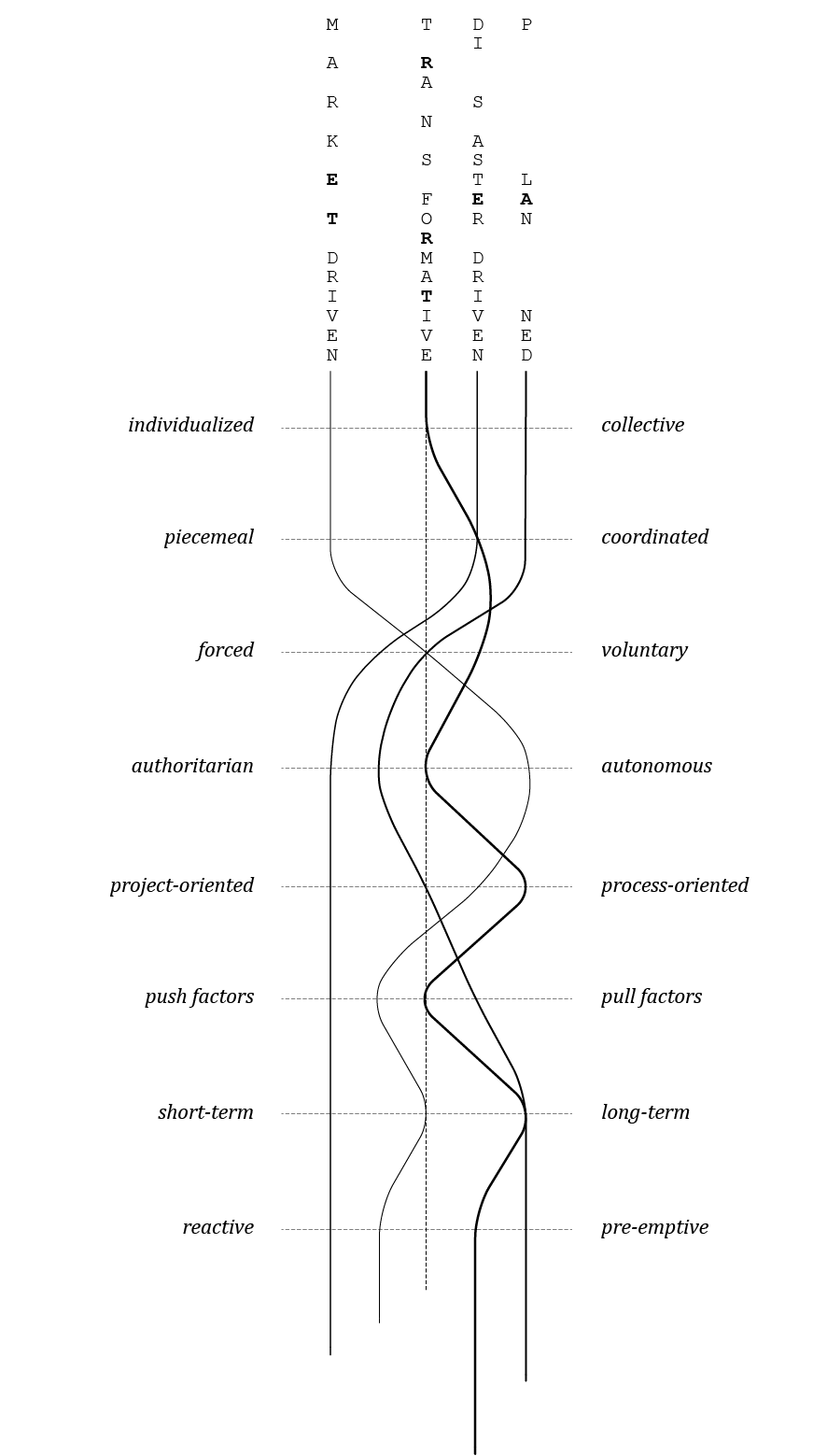

Disaster-driven retreat is the post-disaster relocation of people away from hazard areas. It is the permanent relocation of individuals or groups following the immediate disaster response and temporary re-housing scheme. Disaster-driven retreat is characterised by being authoritarian, top-down, reactive, and short-term. It is following a project logic that is measurable in terms of construction costs and the number of people and households being relocated.

Market-driven retreat is the gradual, uncoordinated and often hidden displacement of people due to risk exposure, increased frequency of hazardous events, and restricted access to mortgage loans or insurance coverages. Market-driven retreat can have spillover effects on neighbouring communities located outside hazard zones and lead to climate gentrification in receiving areas. Market-driven retreat is characterised by individualised costs and risks that impose uneven burdens on vulnerable and socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

Planned retreat refers to the pre-emptive and coordinated change of land use over a long time. It is characterised by being government-led, authoritative, and serving the greater good of society. For instance, the provision of land for nature restoration and the promotion of biodiversity can be a pull factor that drives the retreat process, rather than having human hazard exposure as the sole and dominating push factor for change. Planned retreat is implemented through regulatory incentives, such as zoning, insurance conditions, and risk disclosure laws.

Transformative retreat emphasises local, collaborative, network-based and democratic processes that empower communities to envision, work with, and take action on retreat as a desired process of change. Transformative retreat is largely bottom-up, process-oriented, and concerned with deep systemic changes, including e.g. intergenerational equity and multispecies justice. Key features include site-specific experiments and learning loops that challenge the mindset, combined with knowledge exchange across geographical and cultural settings.

The four types of retreat have different rationales, timelines, and power balances. Figure 1 indicates the weighting of eight key factors influencing and sometimes dominating the processes of retreat in policy and planning, with a descriptive storyline for each of the four types of retreat.

General cultural conceptions of retreat impede retreat as a policy option

To some, ‘retreat’ is a controversial and undesirable policy option and a negatively loaded term with connotations of surrendering. Arguably, seeing retreat as defeat challenges the notions of growth, development, and human mastery of nature.

Breaking down the word, ‘retreat’ can also be cast in a more positive light as re- (‘going back’) and treat (‘to heal or cure’). As an example, ‘going on a retreat’ means to provide a safe refuge and a span of time for reflection.

It might be relevant to stress the first syllable, rather than the second: ‘RE-treat.’ That is, re-treating the landscape and re-treating the relationship between human habitation and natural processes. As such, ‘retreat’ is calling for more human humility concerning the forces of nature.

To combat the negative perceptions of ‘retreat’ and to frame retreat as a feasible, necessary, and desired policy measure, alternative terms have been proposed, such as ‘managed realignment’ and ‘graceful withdrawal.’

Yet, acknowledging the ambiguity of the term ‘retreat’ as having both militaristic and spiritual connotations can be more relevant and more realistically operational since it combines the notions of physical retreat and mental retreat, the tangible and the intangible, the procedural and the restorative, the spatial and the temporal, the physical and ecological territory, as well as the social and economic human actions, which are all intertwined in retreat processes.

An ecological view of nature is a framing condition for retreat

Anthropocentric concerns about retreat as a policy option tend to revolve around environmental push factors, landscapes of grief, loss of tangible human assets, and ultimately the capitulation of human civilisations to nature. Moving forward today, these factors need to be acknowledged and challenged.

From the outset, ‘retreat’ is more ecocentric and less anthropocentric as a climate adaptation strategy compared with protection and accommodation. ‘Retreat’ fundamentally challenges the perception that we humans always can and should build our way out of trouble. This, in isolation, is problematic since structural responses to climate change, e.g. building dikes or increasing sewer capacity, come with a massive carbon footprint and hence risk sacrificing the planet in our endeavour to save human assets.

Embracing the ecological view on nature highlights retreat as a way to restore sensitive ecosystems, provide landscapes of hope, embrace intrinsic values, stimulate regenerative praxes, and provide new narratives guided by environmental pull factors and desired long-term futures, both locally and globally.

At the operational level, it might be increasingly relevant today to work with disaster-driven, market-driven, planned, and transformative retreat in tandem, yet emphasising the importance of transformative retreat over market-driven retreat. That is, to highlight the need for long-term, coordinated, ecologically grounded, deeply democratic, and just processes of retreat.

References

Bragg, Wendy K., Sara T. Gonzalez, Ando Rabearisoa, and Amanda D.a Stoltz. 2021. "Communicating Managed Retreat in California." Water 13 (6): 781.

Fryd, Ole, Anna A. Lund, and Gertrud Jørgensen. 2025. ”Re-treating Coastal Urban Landscapes: A Framework for Managed Retreat.” In Planning and Designing Cities for a Rising Sea Level, edited by Gertrud Jørgensen, Tom Nielsen, Karsten Arnbjerg-Nielsen, and Kamilla S. Møller, 389-412. Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press.

Glavovic, Bruce, Richard Dawson, Winston Chow, Matthias Garschagen, Marjolijn Haasnoot, Chandni Singh, and Adelle Thomas. 2022. “Cities and Settlements by the Sea”. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability, IPCC, Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2163-2194. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hanna, Christina, Iain White, and Bruce C. Glavovic. 2021. “Managed Retreats by Whom and How? Identifying and Delineating Governance Modalities.” Climate Risk Management 31: 100278.

Koslov, Liz. 2016. “The Case for Retreat.” Public Culture 28 (2): 359–387.

Mach, Katharine J., and A. R. Siders. 2021. “Reframing Strategic, Managed Retreat for Transformative Climate Adaptation.” Science 372 (6548): 1294-1299.

Pinter, Nicholas, Mikio Ishiwateri, Atsuko Nonoguchi, Yumiko Tanaka, David Casagrande, Susan Durden, and James Rees. 2019. “Large-Scale Managed Retreat and Structural Protection Following the 2011 Japan Tsunami.” Natural Hazards 96: 1429–1436.

Plastrik, Peter, and John Cleveland. 2019. Can it Happen Here? Improving the Prospect for Managed Retreat by US Cities. Tamworth, New Hampshire: Innovation Network for Communities.

Siders, A. R. 2019. “Managed Retreat in the United States.” One Earth 1 (2): 216-225.

The Clash. 1982. “Should I Stay or Should I Go.” On Combat Rock. Written by Topper Headon, Mick Jones, Paul Simonon, and Joe Strummer. London: Epic. Released 14 May 1982.