Recycling Circle

Henriette Steiner

Related terms: Club of Rome, consumer society, everyday environmental action, micro histories, recycling, waste management

The Limits to Growth and Circularity: A Microhistory

In the early 1970s, Danish civil engineer Tage Mikkelsen (1934–2024) read the work of the Club of Rome, a group of researchers and business leaders in various fields who had been working collectively since 1968 to analyze the state of the world in the wake of Western industrialization. They were critical of the problems facing the world in the late 1960s, such as poverty, pollution, resource consumption, and other crises. Particularly in relation to resource consumption, the interdisciplinary book-length report The Limits to Growth, published by several members of the Club of Rome in 1972, stated that the exponential growth of the economy and consumption had to be stopped: limits had to be set to growth itself (Meadows 1972). The argument was a scientific as well as an ethical claim and set Tage Mikkelsen on a mission to promote recycling in Denmark by furthering the reuse of the growing amounts of waste. One goal was to put a limit on the use of raw materials that went into production itself as an attempt to counteract the overconsumption of the Earth’s natural resources. This was an idea he would work on for several decades to inspire systemic change through entrepreneurship, business, education, and cross-sectoral collaboration. This idea is reflected in the recycling symbol (see Figure 1) – a circle with three arrows pointing into each other – which Tage designed in 1976 with reference to the similar triangular recycling symbol drawn in 1970 by the American Gary Anderson (see Figure 2). To many people and organizations today, this well-known symbol epitomizes the process of recycling, and it is still used in different variations in Denmark and all over the world.

Tage Mikkelsen’s is an alternative story about what has given Denmark a reputation for pioneering environmental concerns and policies. Yet it is also a story that reveals some of the cracks in that image. It is a microhistory from which we can learn something today, when we are determined to find new systems and processual approaches to circularity and recycling, considering the increasing ecological crisis, approaches that can cut across politics, organizations, civil society, and private companies. As a microhistory, it also shows the power of storytelling as a way to allow people to connect with environmental issues and history, science, and ethics, suggesting pathways and pitfalls on a scale to which individuals can relate (Jørgensen 2023). At the same time, it points to the limits of an anthropocentric and techno-optimist framework.

Mounting Waste and The Limits to Growth

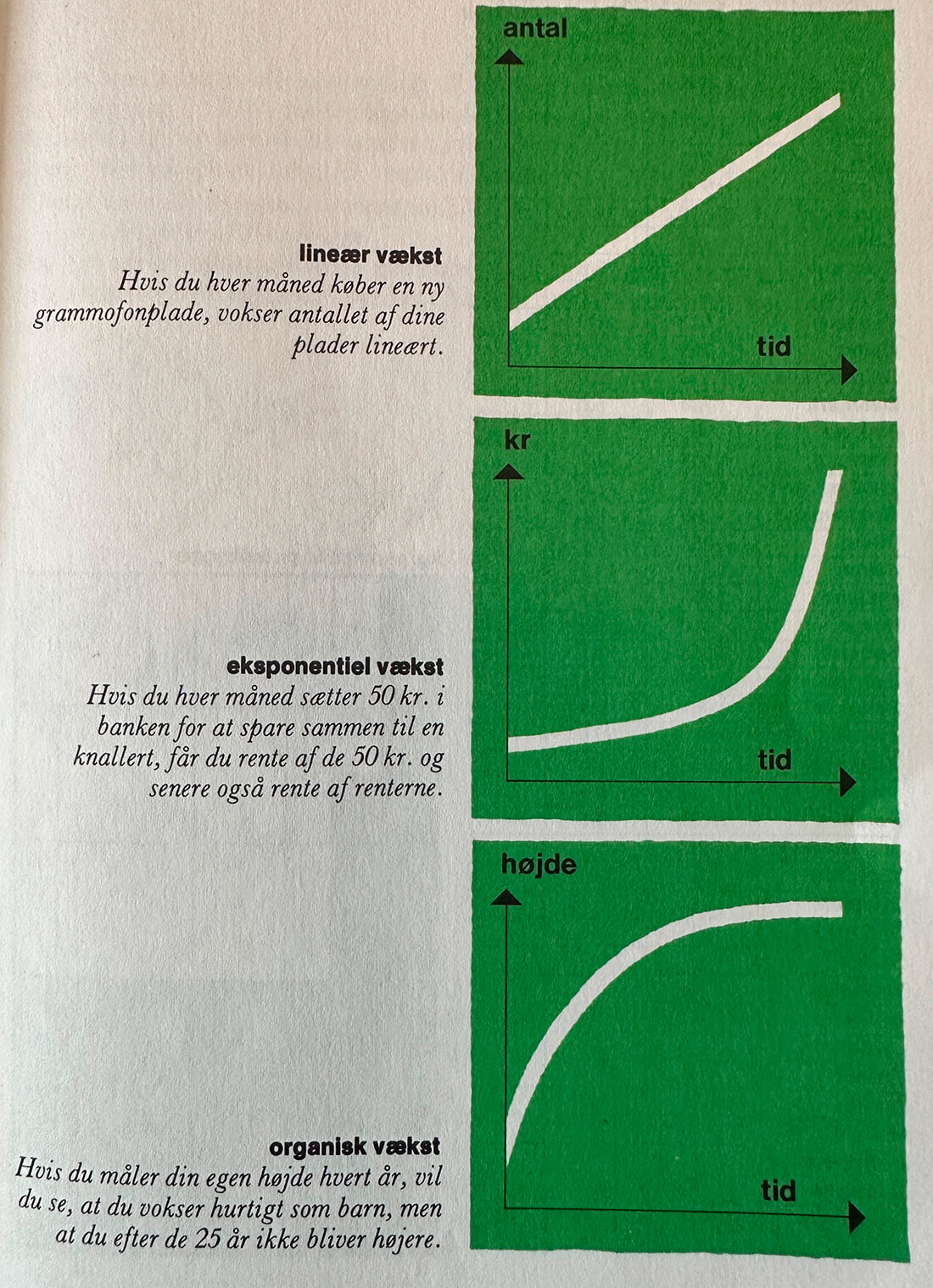

The Club of Rome and The Limits to Growth described the dangers of exponentially increasing production and consumption of resources in modern societies. Its argument developed along the lines of the highly anthropocentric thinking around sustainability of the UN’s Brundtland Commission of 1987, with the goal of “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” and within a techno-optimistic framework (Brundtland). Their proposed solution was that Western postwar industrialized societies set limits to growth in ways that would find an organic, balanced system which would still permit living a modern life on Earth, also for future generations, and thus to stop the exponential growth and resource consumption of this period. Indeed, together with his wife and teacher Anita Mikkelsen, Tage Mikkelsen developed teaching material for eighth graders which described the difference between linear, exponential, and organic forms of growth in a way that would resonate with teenagers (see fig. 2).

This publication from 1976 encouraged youngsters to think about different growth paradigms (See Figure 3). Linear growth is here explained through the metaphor of an individual sequentially buying new records, adding to one’s music collection one record at a time. Exponential growth, in contrast, is explained as an individual placing a monthly deposit of DKK 50 into their bank account to save up for a moped – growth of funds stems not just from the accumulated deposits but also from compound interest provided by the bank. Finally, organic growth is explained through the metaphor of the growth of a child, which starts fast but flattens in early adulthood. Whilst this conceptual framework paves the way for an understanding that growth can be human-made, serve different purposes or be a naturally occurring process, we may of course note just how effortlessly the individual experience is telescoped to a societal or even a planetary scale. The metaphors balance consumer desire (records) and perceived necessity (the moped) of a young, relatively well-off person in Denmark in 1976. Yet, from the Mikkelsens’ point of view, the recent experience of exponential growth of industrial production ought to be stalled and a different growth paradigm should transpire – one that calls on the anthropocentric metaphor of organic human growth. This would be one which, rather than consciously seeking to maximize growth organically, allows the modern lifeform of Western industrial capitalism to unfold responsibly, with a balance between human-made and other systems on which humans depend. Yet, at the same time, the organic metaphor calling on images of maturation, coming of age, or even Bildung, posits said life form as an absolute, glossing over its highly situated historical and economic underpinnings. Nevertheless, the Limits to Growth framework, here recast in a metaphoric language suitable for Danish eighth graders in 1976, can be seen as an early articulation of what we speak of today as “planetary boundaries” (Richardson et al. 2023). It thus reflects a way of thinking that is based on research and modern technical science, but it is also an ethical statement, posing the question of how Western, modern, industrialized societies may mature as a way for humans to live in harmony with the environment in the future. Complicating matters, however, the authors of The Limits to Growth were notoriously skeptical of whether modern technology, as co-creator of the crises, was always the best at resolving them (Meadows 1972, 13).

From Cardboard to Caviar

At the time he read the work of the Club of Rome, Tage Mikkelsen was director of a company that produced packaging made from cardboard and other materials. In an interview conducted in 2019, he described the report as so eye-opening on an ethical level that he could no longer envisage himself contributing to overconsumption and unnecessary production by making disposable cardboard packaging (Mikkelsen 2019). Something needed to be done.

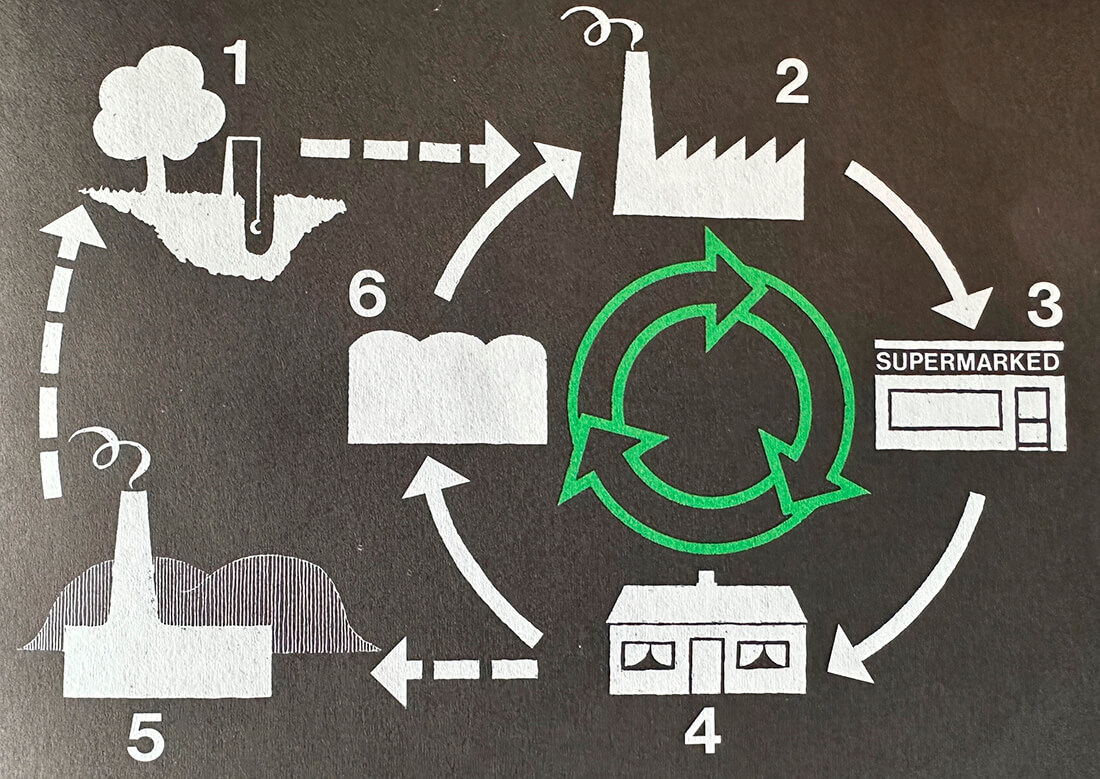

In 1974, Tage Mikkelsen thus founded the company Gendan A/S. It specializes in waste analysis, intending to certify the share of recycled materials in a product. If a product like cardboard, paper, glass, or a plastic bottle was produced with more than 45% recycled materials, it would qualify. Tage also experimented (sometimes in his own backyard) with letting worms eat cardboard and packaging to create compost, a process familiar today from fish food companies under the slogan “from cardboard to caviar” (Carter 2003). This emphasizes the way we may talk of different forms of recycling, spanning, as Mikkelsen wrote, reuse of a particular object (“genbrug”), recycling of materials (“genanvendelse”), extraction of energy from already produces materials, e.g. in incinerators (“genudvinding”) and extraction of raw materials from previously produced products (“genvinding”) (Mikkelsen, word list on book cover). The latter was the word that Mikkelsen used for his recycling circle, and, as seen in Figure 4 below, it emphasizes the link to modern industrialized production.

Certainly, as the recycling circle may somewhat falsely indicate, we do not have to do with a perfectly circular movement where the same material rematerializes again and again in identical form. It takes a steady influx of natural resources and particular energy-intensive modes of production. Yet, the idea here is to turn household waste into something cheap, omnipresent, and inevitably extant into something else, even something potentially luxurious and highly valuable. This is not unlike when Copenhagen municipality, in their 2013 campaign, describes their recycling strategy as a potential alchemistic processual movement, claiming that “recycling is gold” (“genbrug er guld”) (København n.d.). Nevertheless, Mikkelsen’s company successfully worked to encourage the use of products made from recyclable and/or recycled materials. In particular, the progressive Danish supermarket chain Irma adopted products bearing Mikkelsen’s recycling symbol. If you bought products such as kitchen rolls or toilet paper with the recycling symbol, you could be sure that at least 45% of the material was recycled paper. This clear, simple system, developed on market premises, found its way into many people’s homes and became a quick and easy way to make environmentally friendly consumer choices.

Yet, although 100% circularity and the recycling of all materials were not an achievable goal, or even the only goal, Tage Mikkelsen and Gendan A/S assured consumers and producers that they were well on their way, setting limits to growth by enabling particular forms of recycling. Drawing on private initiative, technical ability, good resources, privileged opportunities for risk-taking, skilled partners, and a system that was not just marketable but also importantly scalable, Tage Mikkelsen created change for companies and trading spaces in Danish people’s everyday lives. He did this during a period when many people wanted to make more environmentally friendly choices, and when many across the whole political spectrum were concerned about whether nature and society could withstand the furiously overconsumptive growth on which late modern industrial and post-industrial societies and postwar Western capitalism were built. Tage Mikkelsen worked with waste analysis and the recycling concept to change that framework from within and in a way that was visible in people’s everyday lives – to great effect.

The Need for Sustainable Solutions

The post-war growth in industrialized production went along with an acceleration of disposable consumer products and thus of waste. Avoiding huge waste depots, large waste incinerators were built in Denmark, in this way utilizing waste as a resource, e.g., to create district heating, a technology that has been touted for decades in Denmark and a cornerstone in what has enabled the city of Copenhagen to use a world-renowned strategy of lowering emissions and the use of fossil fuels. Yet, this approach comes with certain dilemmas: not just the trivial claim that waste is itself a product of industrialized production. As recently as 2017, Copenhill – a high-tech waste-to-energy plant designed as an architectural icon and funscape with a ski hill on top and touted as a pinnacle of Copenhagen’s sustainable urban politics – opened amidst reports that Copenhageners no longer produced enough waste for the incinerators, given the city’s introduction of increased recycling at a household level (Staff 2019). Even in the early days of these technologies, however, people such as Tage Mikkelsen were questioning whether waste burning was always a good solution – burning waste that was full of valuable materials that could be recycled. To counteract this burn-it-all trend, and in recognition of the – as he later lamented – hugely difficult need for cross-sectoral dialogue, Mikkelsen’s company Gendan A/S organized yearly conferences bringing together different stakeholders to work towards increasing recycling and reuse.

Today, many sectors are moving into a new paradigm based on notions of circularity and recycling, including many efforts to generate new types of building materials in the highly resource-intensive and pollutant construction industry involving architecture, infrastructural construction, and urban development, making the less than ten-year-old Copenhill development seem to be a product of a distant past. This is no longer a story about toilet paper, kitchen rolls, or cardboard boxes, but rather one about concrete, tiles, soil, wood, iron, and other materials used in the construction industry to build or renovate buildings, infrastructures, and urban commentates. What opportunities do we have to create change in such an industry from within? What are the opportunities to exert influence, spark change, and create scalable solutions within the logic on which such an industry is built? There seem to be many similarities with the situation in which Tage Mikkelsen found himself in 1972.

What are the possibilities for creating change – both systemically and within individual projects? The microhistory of Tage Mikkelsen offers an interesting mirror. Despite its everyday groundings and limited perspectives from the economically privileged place and history of Denmark in the latter decades of the twentieth century, as a story, it shows that it is possible to take responsibility and work systematically and consciously for scalable solutions. It must be said that Tage Mikkelsen’s is also a story about decades of frustration during his attempts to influence decision makers and create more systemic change. This is therefore also a story about the limits of influence, and about the intersections between micro- and macro-history, the individual and the collective. It points to the kinds of limits of an anthropocentric and techno-optimist framework that have been laid bare in recent decades of research in various fields, including environmental humanities, ecofeminism, new materialism, posthumanism, and critical animal studies. It is a fact, however, that the Club of Rome’s conclusions remain valid, and that many people today see the need for change and want to act. Doing so, we can learn from microhistories like this and be inspired by individuals’ power and determination to bequeath our planet and society to future generations, in ways that help us set limits to growth and use technological solutions rooted in different values and in different ethics.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are owed to the generosity and hospitality of the Mikkelsen family. This entry is based on an oral history interview with Tage and Anita Mikkelsen, conducted on August 21, 2019, in Vedbæk, Denmark, by Henriette Steiner and Nanna Bonde Thylstrup.

References

Brundtland, Gro Harlem. 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carter, Helen. 2003. “From Cardboard to Caviar.” The Guardian, 2003/02/12/T02:36:27.000Z, 2003, UK news. Accessed 2025/06/26/15:48:30. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2003/feb/12/helencarter.

Jørgensen, Gertrud; Heidi Svenningsen Kajita and Henriette Steiner, eds. 2023. Stories as Solutions. 13 Historier om bæredygtige løsninger for byer og landskaber/13 Stories about Sustainable Solutions for Cities and Landscapes. Department for Geosciences and Natural Ressource Management, University of Copenhagen. https://ign.ku.dk/green-solutions/stories-as-solutions Accessed 23 June 2025.

Meadows, Donella H., and Club of Rome. 1972. The Limits to Growth. A Report for the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books.

Mikkelsen, Tage. 1976. Genbrug og Dig. Copenhagen: Kommunetryk. København. N.d. ”Genbrug er Guld – for Københavns Kommune”. accessed 23 June 2025.

Richardson, Katherine, Steffen Will, Lucht Wolfgang, Bendtsen Jørgen, E. Cornell Sarah, F. Donges Jonathan, Drüke Markus, Fetzer Ingo, Bala Govindasamy, and Bloh Werner von. 2023. "Earth Beyond Six of Nine Planetary Boundaries" Science Advances 9 (37).

Staff, Z. W. E. 2019. "A Danish Fiasco: The Copenhagen Incineration Plant" Zero Waste Europe (blog). June 23, 2025.