Place

Robert Boschman

Related terms: Space, Site, Territory, Time, Region, Land, Landscape, Dwelling, Building, Memory, Environmental History, Critical Zone

[W]e knew nothing where we were, or upon what land it was we were driven, whether an island or the main, whether inhabited or not inhabited.

No sign of life anywhere. It was no country that he knew. The names of the towns or the rivers.

Thousands of years of occupancy on their lands taught tribal peoples the sacred landscapes for which they were responsible and gradually the structure of ceremonial reality became clear. It was not what people believed to be true that was important but what they experienced as true.

The environmental crisis is arguably one of place and of how place is interpreted in the context of culture and history. I come from a place named Prince Albert in the province of Canada called Saskatchewan. Recently in the news I read that only a short distance from Prince Albert (a small settler city found along the shores of the North Saskatchewan River), “the Âsowanânihk Council, meaning ‘A Place to Cross’ in Cree,” is working closely with local universities and Indigenous communities to preserve a recently-discovered site that’s been determined to be 11,000 years old.[1] Local Indigenous leaders from the Sturgeon Lake First Nation are collaborating with archaeologists to protect the site “from logging and industrial activity.” Chief Christine Longjohn is quoted as stating that “this site speaks for us, proving that our roots run deep and unbroken.” The researcher who first came upon this “long-term settlement” recounts his experience in the following terms: “The moment I saw the layers of history peeking through the soil, I felt the weight of generations staring back at me.” Discovering the remains of a settled human place with this timestamp would make the news anywhere, but here on Turtle Island, the myth of empty land – terra nullius – still holds and is acted upon (Harding 2014, 27-48; Mann 2005, 155; Truth and Reconciliation Commission Summary of the Final Report 2015, 46).

[1] On the differences between place and site in archaeological practice, John Carman writes, “The sense of the place where the excavation is located is never part of the discourse of archaeology. The conventions are to locate sites in terms of plans, maps, and aerial photography […] but not in terms of the experience of landscape and cultural meaning […].” (97).

In the history of this same region, the myth of empty land made it possible for the Reverend James Nisbet in 1866 to give the name Prince Albert to a high spot along the river’s south bank in honor of Queen Victoria’s late husband, even though this place had long possessed a name, kistapinânihk, which translates roughly into English as “sitting pretty place” but also “great meeting place” (Boschman 2021, 7 and 40). Terra nullius, in conjunction with the Doctrine of Discovery, gave the expansionist westward colonisation of North America a momentum it would not have possessed had its people, places, regions, and histories been recognised and respected. Deloria (1973) makes this point vitally clear: “American Indians hold their lands – places – as having the highest possible meaning, and all their statements are made with this reference point in mind. Immigrants review the movement of their ancestors across the continent as a steady progression of basically good events and experiences, thereby placing history (time) in the best possible light.” (61) As though there could be no alternative, the idea of an empty continent permitted European explorers, financed by their sovereigns and investors, to name and take the lands and places they encountered in short order. Michele de Cuneo, one of Columbus’s men sailing with him in the Caribbean in 1495, baptised an island with the name La Bella Saonese: “For well it is called beautiful, for in it there are 37 villages with at least 30,000 souls” (61).[2] According to de Cuneo, his Lord Admiral, Columbus, gifted him the island as they approached and “noted [it] down in his book.” Bartolomé de las Casas, himself at one time an encomendero like de Cuneo (Mann 2005, 38-9), later documented the environmental destruction and depopulation of islands such as this throughout the Caribbean.

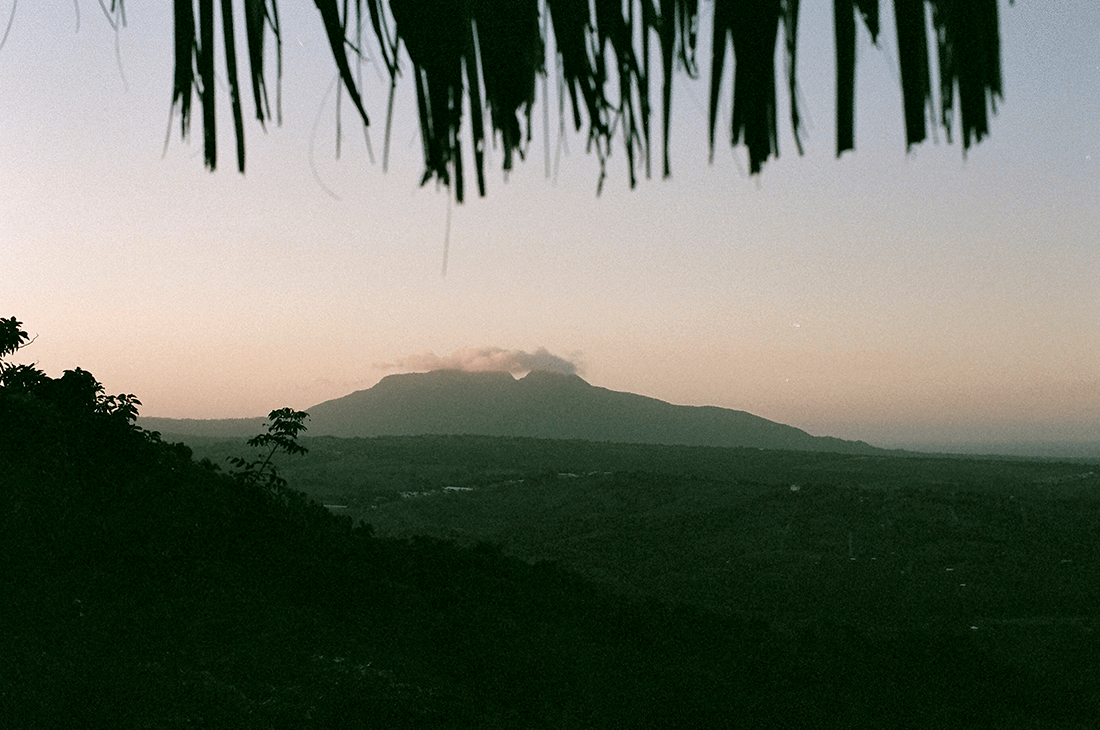

The Taino people Columbus met on the island he named Hispaniola in 1492 no longer exist today [Figure 1]. By the time de las Casas published A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies in 1552, the Taino were decimated and their forests cut down (Mann 2005, 206; Hooghiemstra et al, 2018). Yet the places they created and named during the millennia of their dwelling there gave them their sense of identity and orientation; exuded ancestral and spiritual presences; connected them to time and memory; were encountered experientially and relationally; and integrated inside and outside in their buildings (Oliver 2009, 62, 67, and 144). These are the features of place that I want to outline briefly here as important from an Environmental Humanities perspective.[3] Although, as Tuan and others have written, place can have many meanings (Massey 2005, 130-142; Tuan 1977, 161), the features of place listed above may be found among many peoples and cultures, Indigenous as well as migrant and settler. I would also submit that the concept of place is fraught with both the past and current actions of colonisation, which in our age spawns many non-places (Augé 1995, 77-8). Marc Augé in Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthology of Supermodernity (1995) argues that place has three “characteristics in common […] places of identity, of relations and of history” (52). A non-place “cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity” (77-8). Like the Lord Admiral Columbus noting down the name La Bella Saonese in his book, there is a seeming casualness with which colonising forces carry out place-related practices that erase cultures and damage ecologies. It is this attitude, one of relentless and entitled acquisition and development, which the Canadian anthropologist John A. Livingston called “the northern industrial-growth ideology” (70), that has the Âsowanânihk Council so worried about preserving the 11,000-year-old site it now stewards just a few kilometres from Prince Albert.

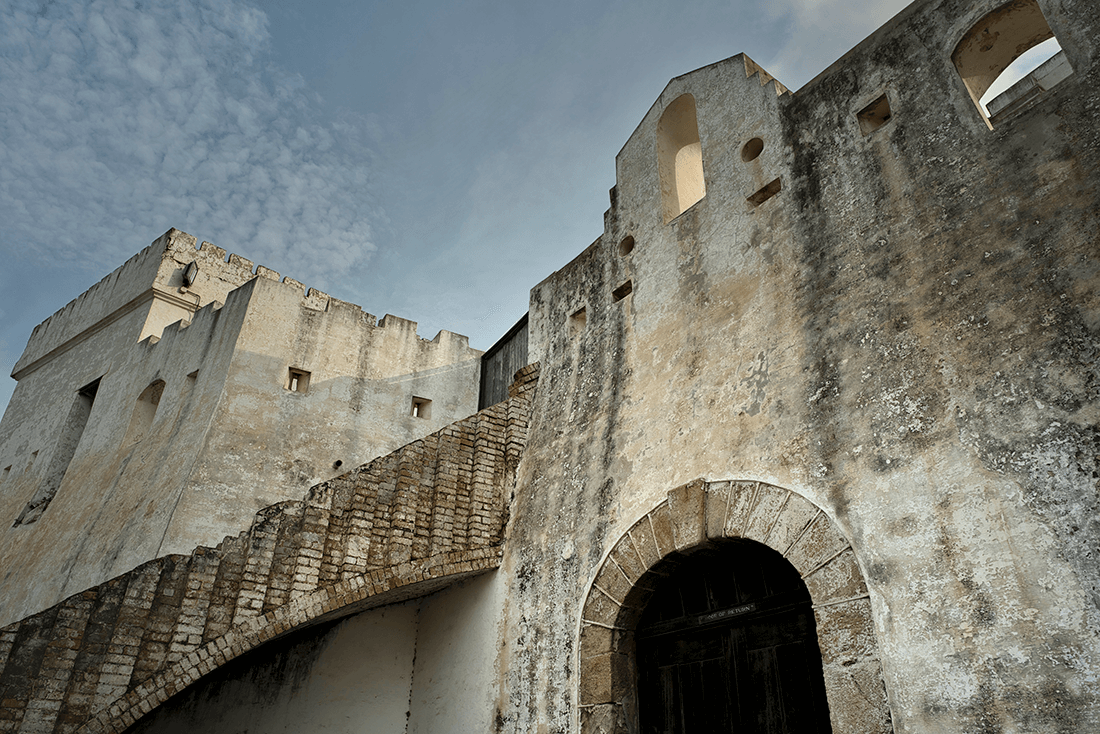

The philosopher Edward S. Casey begins Getting Back into Place: Toward a Renewed Understanding of the Place-World (2009) by asking the reader to imagine being lost at sea, completely disoriented, out of place (3-22). This oceanic narrative tack is also used by storytellers, from Homer to Daniel Defoe and Cormac McCarthy. Casey employs it to examine the historical relationship between longitude and time (and therefore knowing where one is); in doing so, he also argues that place is actually before time and space and, indeed, gives these otherwise pre-eminent concepts their orientative meaning, not the other way around: “place […] is at once the limit and the condition of all that exists” (15).[4] Casey makes place (and being emplaced) central to knowing who and where you are, and getting lost (displaced) at sea helps to demonstrate his case. I would add that anyone reading the memoir of Olaudah Equiano (1785), in which he recounts being kidnapped into slavery at the age of twelve, can never forget the utter terror he describes on boarding a waiting ship off the coast of Nigeria: his inland home among the Igbo becomes so powerful at this point – in other words, his knowing with his very body his own home-place – that he wants to die. Anyone reading Lance Rediker’s The Slave Ship: A Human History (2007), in which an entire chapter, including a telling section called “Home” (110-113), is devoted to Equiano’s experience, will discover an unsettling historical narrative wherein “the slave ship was a strange and potent combination of war machine, mobile prison, and factory” (9). Over the four centuries of its existence, colonial traffic in Africans displaced “an estimated 14 million people,” of whom 1.8 million died en route during the Middle Passage and were thrown overboard (5).[5] Marcus, an African American character in Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (2016), finds himself “terrified” by the ocean, “all that space,” and remembers how “his father told him that black people didn’t like water because they were brought over on slave ships. What did a black man want to swim for? The ocean floor was already littered with black men.” (284) As I saw for myself when I visited Ghana in 2022, the Door of No Return at Cape Coast Castle has been renamed The Door of Return [Figure 2], as descendants of enslaved Africans return to reclaim their ancestral places, like the characters of Marcus and Marjorie do at the end of Gyasi’s Homegoing.

If Casey’s dictum is that “to be is to be in place” and therefore placial (16) – making place quite distinct from space and territory – then we must empathize with the plight of the placeless, who feel severed from the source of their identity and orientation as well from their ancestors, and suffer as a result (Casey 1993, 35). Albrecht (2019) has offered the term solastalgia for the sickness felt by those whose sense of place has been negatively impacted by, for instance, environmental change brought on by industrialisation and a warming climate (38). It takes a lot of cement – a major contributor to carbon emissions (Hawken 2017, 162-3) – to build the non-places that spring up everywhere on the planet: malls, airports, etc. Solastalgia, a neologism derived from nostalgia, solace, and desolation, has become a global phenomenon as non-places proliferate across the Anthropocene landscape (41-44). On the other hand, when I met the legendary Métis writer Maria Campbell at Nistowiak Falls in northern Saskatchewan in the summer of 1990, she used the term power place to describe the landscape in which we stood, our fishing lures travelling rapidly through the currents rushing past the shore [Figure 3]. She said that there are islands in the area where you should not camp; these are ancestral places, and the spirits that dwell in them would take down your tent if you didn’t belong (Boschman 2021, 291). David Abram (1996) writes about the moral power of place in Western Apache culture and thought, wherein place has the power to intervene in human affairs (155-162) and may “stalk” one who is not in “right relations” within the community (157). To be emplaced is to be connected properly by way of ancestral forces, memory, and time (Descola 2013, 34-35; Casey 1993, 318; Deloria 1973, 102).

In Canada, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Summary of the Final Report (2015) makes it clear from the first page that land – and therefore place – is central to both truth and reconciliation in a nation state built on the Doctrine of Discovery and the concept of terra nullius. The commissioners name Canada as a nation state with a recent history in which

Land is seized, and populations are forcibly transferred, and their movement is restricted. Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. And, most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next. (1)

Survivors of Canada’s Residential Schools System, such as Archie Hyacinthe, consistently testify to the rupture caused by forced displacement: “That’s when the trauma started for me, being separated from my sister, from my parents, and from our, our home. We were no longer free. It was like being, you know, taken to a strange land, even though it was our, our land, as I understood later.” (39) In the TRC’s Calls to Action (2015), Canada is called upon to “Repudiate concepts used to justify European sovereignty over Indigenous lands and peoples such as the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius” (5). Canada is also asked to amend its policies concerning historic sites and monuments in order “to integrate Indigenous history, heritage values, and memory practices into [its] national heritage and history” (9). As Jay Winter comprehensively argues in “Sites of Memory,” commemorative places “in the epoch of the nation-state” (312) instantiate and sustain historical remembrance, political power, economy, art, and ritual (313-324).

Winter also argues that such sites are unsustainable (324) and often vanish, only sometimes to reappear again. They are created by cultures, and cultures are in constant flux. Place is unstable (Massey 141) and phenomenological – experienced and known by the subject – as well as relational – linked to others, both living and dead, human and nonhuman. In his post-apocalyptic novel The Road (2006), Cormac McCarthy evokes the precarity of place throughout the text, but nowhere more tellingly than the mid-point scene in which the father and son discover an undisturbed bunker filled with the consumer goods of a lost age. While the father remembers this former time, he’s acutely aware that his son knows nothing of “The richness of a vanished world. Why is this here? The boy said. Is it real? Oh yes. It’s real” (117). In this temporary – because unsustainable – underworld oasis, the two are replenished and restored to continue their quest for a place to call home in the company of others who are like-minded. The father and son cut their hair and shave in front of a mirror and play checkers; they say thank you for what they’ve been blessed to find, and the father is “visited in a dream by creatures of a kind he’d never seen before” (129). At the precise mid-point of the novel, the pair set out again with their hair and bodies ritually washed and pushing a new grocery cart (130). Many of the characteristics of place that I have outlined here are present in this scene, with its rich intertextual echoes of human storytelling. The father and son regain their sense of identity and orientation, though this is extremely painful for the older man; the bunker contains ancestral and spiritual presences; the pair are temporarily reconnected to time and memory; and, especially powerful, the bunker, as a wellspring of sustenance, is encountered experientially and relationally. The father is aware that without this place, he could not go on (121). What the bunker lacks, however, is integration, and the father urgently knows this also.

When I teach The Road, I invite students to discuss the father’s decision that they cannot stay in this place of such plenitude. Together we wrestle with the question, Why do they leave? And what would I do? Leave or stay? These are potent questions – and I know that I ask the same questions again each time I reread McCarthy’s novel. But surely from the father’s perspective, leaving is necessary because this dream-like underworld, replete with canned peaches and blankets and toilet paper, is not integrated with the wasteland outside. When an environmental catastrophe of global dimensions takes place, it has the power to render place null and void; in a very real sense, then, McCarthy’s novel depicts the revenge of terra nullius on Livingston’s “northern-industrial growth ideology.” Inside and outside no longer talk to one another – they are severed. The father’s quest for cultural and spiritual meaning, therefore, does not and cannot involve hunkering down in a heretofore undiscovered survivalist bunker but rather means delivering his son to an intact human community, if one can be found, or else die trying.

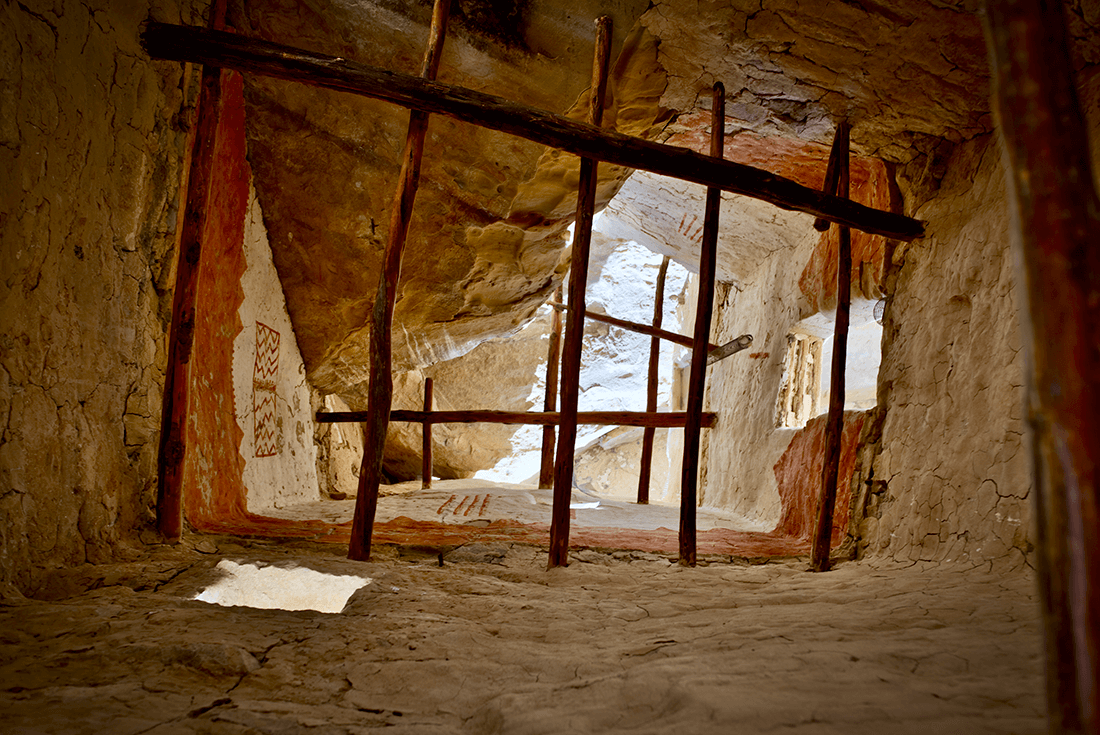

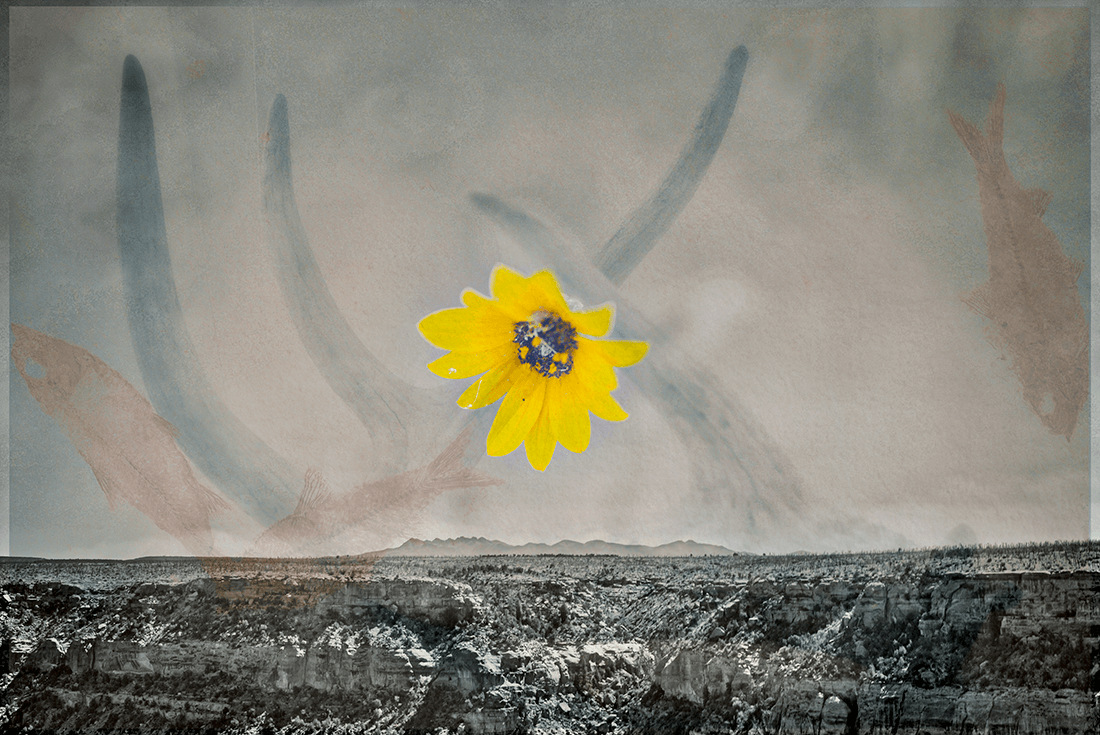

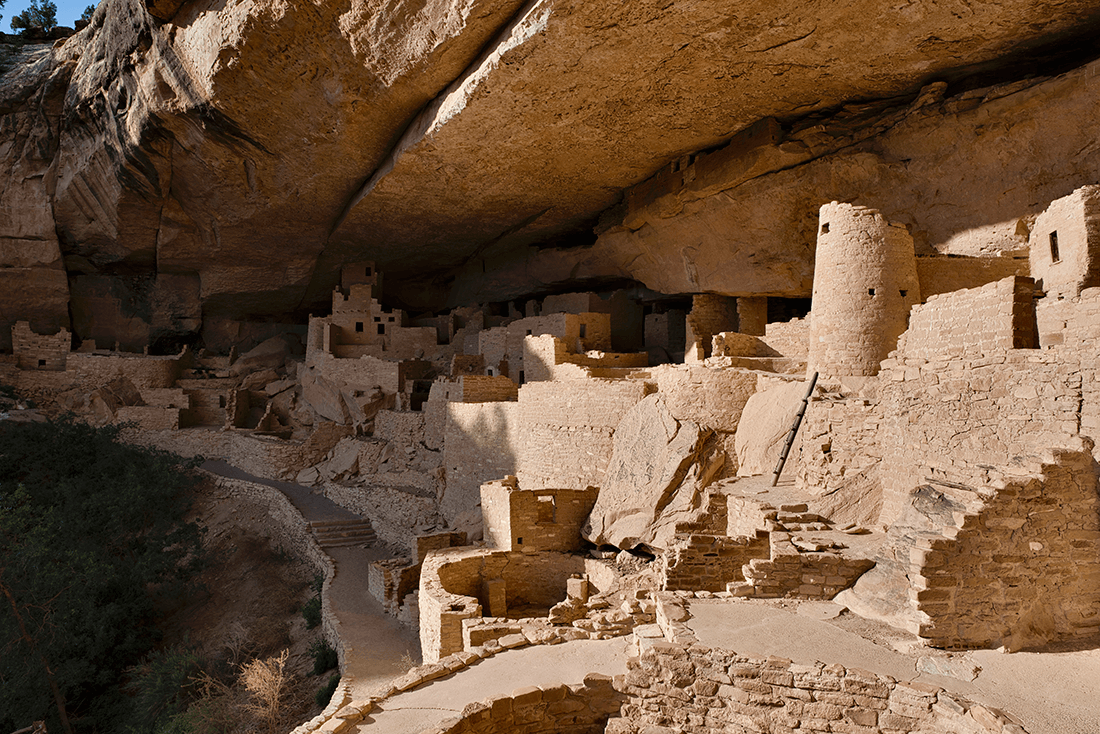

Buildings, ideally, exist in relational harmony with their surroundings. I saw this for myself when I visited Cliff Palace, in the Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, in 2018 and was permitted to lie on my back and insert my head and shoulders through an opening into the interior of an ancestral Pueblo dwelling. What I saw there – and managed to gather with a pretty good camera – demonstrated for me the integration of inside and outside in a preserved place from the distant past [Figure 4]. Inside, I saw an ochre painting of mountains ringing the walls and intersecting with a window that looked out on the canyon and beyond; outside, above the lip of the canyon, stands the line of mountains, visible far off in the distance [Figure 5], from which I later composed a layered photograph, a visual palimpsest. Outside the interior scene, the visitor encounters roofless kivas with their ever-present and underworldly sipapus that in ancient Pueblo cultures connect inhabitants with the earth from which they and all living beings are thought to emerge (Fraser 1986, 19; Abram 1996, 218) [Figure 6]. South of Mesa Verde, at Chaco Canyon’s Pueblo Bonito, visitors can see the remains of kivas on a larger scale [Figure 7]; here the human population may have peaked at approximately 2,000 inhabitants (Fraser 1986, 158), in a community designed and built in cosmic harmony with the sun, moon, and stars (Fraser 1986, 259-73). As a visitor to Acoma Pueblo, also known as Sky City, in New Mexico, I learned that kivas continue to play an everyday role in Indigenous communities of the American Southwest.

Place can be experiential, creative, relational, connected to memory and ancestral presence, and integrate inside and outside; place is also powerfully and integrally linked to time and space. I am reminded of these features when I visit a legacy uranium community abandoned by the extractive industrial entities that created it in the first place. On the north shore of Lake Athabasca stand the remains of Uranium City, once a community of some 4,000 people before its reason for existence ceased suddenly in December 1982 when Eldorado Inc., a crown corporation of Canada, abruptly stopped its mining and milling activities (Boschman and Bunn, 2018). In short order, most people left, forced to abandon their mortgaged homes, their businesses, schools, churches, hockey and curling rinks, their cottages and their cemeteries. They couldn’t drive away because there are no roads connecting Uranium City to the south, so they abandoned their vehicles as well. This sudden dislocation caused trauma and grief that continue to this day among the surviving former inhabitants as well as those few who remained. To visit this place is to enter a kind of laboratory in which one can witness nature-culture extremes in real time; as a tree springs up through a kitchen floor in a former human home, the visitor encounters an uncanny arboretum, an interior that is no more but speaks still of its former interiority. Seeing the life force of a poplar tree next to the intimacy of interior paints curated by decades of near-Arctic weather produces strange emotions. One feels schooled by a fierce teacher. To enter such a place – with steel-toed boots, hard hat, cameras, and bear spray – is to experience an arresting stage in what Bachelard (1964, 211) calls “the dialectics of outside and inside”. Cairns and Jacobs touch on this in a discussion of Latour and Yaneva:

In an explicit statement on building technologies, Latour, working with Yaneva (2008), conceives of a building as a “moving project.” For them, architecture is not only designed relationally but, once built, continuously re-forms in relation to the passage of time, as well as the planned and unplanned renovations wrought by the human and nonhuman agents it coexists with. Seen in this way, a building is flow, not form; it is creative, not merely a creation. (66-7)

The thing about visiting a place like Uranium City, where abandonment and the uncanny reign, is that inside and outside break down, become almost hallucinatory: everything seems outside, with significant vestiges of inside everywhere you look; but then suddenly everything shifts, as in a dream, and one realizes, with Aït-Touati and Latour, that now – in this time of accelerating environmental changes – there really is no outside (Latour 2018; Aït-Touati and Latour 2022). We are all insiders, and our planet is a place, our only home (Figure 8).

References

Abram, David. 1996. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Vintage Books.

Aït-Touati, Frédérique, and Bruno Latour. (2022). Trilogie Terrestre: Inside, Moving Earths, Viral. Montreuil: Éditions B42.

Augé, Marc. 1995. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthology of Supermodernity. Trans. John Howe. London: Verso Books.

Bachelard, Gaston. 1969 [1964]. The Poetics of Space. Trans. Maria Jolas. Boston: Beacon Press.

Bird Rose, Deborah. 2004. Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics for Decolonisation. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, Inc.

Boschman, Robert. 2021. White Coal City: A Memoir of Place and Family. Regina: University of Regina Press.

Boschman, Robert, and Bill Bunn. 2018. “Nuclear Avenue: ‘Cyclonic Development’, Abandonment, and Relations in Uranium City, Canada.” Humanities 7 (1: 5). https://doi.org/10.3390/h7010005. Accessed June 20, 2025.

Cairns, Stephen, and Jane M. Jacobs. 2014. Buildings Must Die: A Perverse View of Architecture. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Carman, John. 2006. “Digging the Dirt: Excavation as a Social Practice.” Ethnographies of Archeological Practice: Cultural Encounters, Material Transformations, edited by Matt Edgeworth, 95-102. New York: Altamira Press.

Casas, Bartolomé de las. 1992 [1552]. A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Trans. Nigel Griffin. London: Penguin.

Casey, Edward S. 2009 [1993]. Getting Back into Place: Toward a Renewed Understanding of the Place-World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Cuneo, Michele de. 2022 [1495]. “letter [Concerning Columbus’s Second Voyage].” The Broadview Anthology of American Literature, Volume A, Beginnings to 1820, edited by Derrick R. Spires et al., 60-62. Trans. Samuel Eliot Morrison. Peterborough, ON.: Broadview Press. This letter’s source is as follows: Journals and Other Documents on the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, edited and translated by S. E. Morrison. New York: Heritage Press, 1963.

Defoe, Daniel. 1985 [1719]. The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. Intro: Angus Ross. London: Penguin Books.

Deloria, Vine, Jr. 2003 [1973]. God is Red: A Native View of Religion. Golden, CO.: Fulcrum Publishing.

Descola, Philippe. 2013. Beyond Nature and Culture. Trans. Janet Lloyd. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Equiano, Olaudah. 1789. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. Project Gutenberg Ebook 15399. Accessed June 12, 2025.

Fraser, Kendrick. 2005 [1986]. People of Chaco: A Canyon and its Culture, updated and expanded. New York: W.W. Norton.

Gyasi, Yaa. 2016. Homegoing. Canada: Bond Street Books.

Harding, Wendy. 2014. The Myth of Emptiness and the New American Literature of Place. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Hawken, Paul (ed.). 2017. Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming. New York: Penguin Books.

Hooghiemstra, Henry et al. 2018. “Columbus’ Environmental Impact in the New World: Land Use Change in the Yaque River Valley, Dominican Republic” The Holocene 28 (11), 1818-1835. Accessed June 18, 2025.

Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on livelihood, dwelling, and skill. New York: Routledge. eBook.

Latour, Bruno. (October 22, 2018). “The Politics of Gaia.” Feverish World Symposium. Ira Allen Chapel, University of Vermont. Keynote Address.

Livingston, John A. 1994. Rogue Primate: An Exploration of Human Domestication. Toronto: Key Porter Books.

Mann, Charles. 2011 [2005]. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus.

Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: Sage Publications. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

McCarthy, Cormac. 2006. The Road. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Oliver, José R. 2009. Caciques and Cemi Idols: The Web Spun by Taino Rulers Between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, University of Alabama Press, 2009. ProQuest Ebook Central. Accessed June 13, 2025.

Rediker, Marcus. 2008 [2007]. The Slave Ship: A Human History. London: Penguin Books.

Relph, E. 2008 [1976]. Place and Placelessness. London: Pion Limited.

Sturgeon Lake First Nation Press Release. 2025. “11,000-year-old Indigenous village uncovered near Sturgeon Lake”, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Saskatchewan. Accessed June 14, 2025.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Ottawa, Ontario. Retrieved on 14 Jun 2025.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Accessed June 14, 2025.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. 2014 [1977]. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Figure 7. Interior of Great Kiva, Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Culture National Historic Park, New Mexico. Photograph (digital) by author, standing inside Great Kiva, June 2018.

Notes

[1] On the differences between place and site in archaeological practice, John Carman writes, “The sense of the place where the excavation is located is never part of the discourse of archaeology. The conventions are to locate sites in terms of plans, maps, and aerial photography […] but not in terms of the experience of landscape and cultural meaning […].” (97).

[2] Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Summary of the Final Report (2015) clarifies how terra nullius was not made void by the presence of people already in place “since the Indigenous people simply occupied, rather than owned, the land. True ownership […] could only come with European-style agriculture” (46).

[3] See Augé 1995, 77-8; Ingold 2000, 1652-1695; Casey 1993, 30, 297, 339-40; Deloria 1973, 66; Bird Rose 2004, 198; Relph 1976, 29-43; Tuan 1977, 8-18.

[4] He goes on to argue that Western civilisation has erroneously prioritised time in particular over place: “The gigantomachia between Time and Space – a contest of giants orchestrated by Newton and Leibniz, Descartes and Kant, Galileo and Gassendi – is a struggle that overlooks Place. Place undoes the presumed primordiality of Time over Space as well as the equiprimordiality that both Newton and Reid ascribed to them.” (10)

[5] Slavery has (of course) existed before, and many argue that it still does in other forms.