Niche

Related terms: adaptation, context, ecology, evolution, sustainability

A ‘niche’ is the subset of a habitat that relates to a specific organism. Rooted in the Darwinian theory of evolution, the concept defines fitness and survival as the appropriateness of an organism's formal and material characteristics to a specific environment. Organisms may share a habitat – their common environment or surroundings – but have very different niches. In contemporary common usage, the term has evolved into business parlance: a specialised segment of the market for a particular kind of product or service. But the notion of the niche is also having a contemporary resurgence in the design disciplines, where reconsiderations of the relationships between an object or a building and its environment have become increasingly urgent. The resurgence of the concept and the clarification of the term are important because the concept of the niche removes the separation between the terms animal and environment. It disallows each one to be considered independently. One foot in the organism, one foot in the place, the niche is neither a thing nor a place: it is a relationship. In a niche-thinking practice, designers can no longer develop objects that sit mutely on their site. They must develop relationships, dialogues, and a mesh of interactions with a subset of the environment. This entry charts the origins and evolution of the term niche in the design disciplines today, amid crises of climate change, extraction, pollution, and material shortages.

The term ‘niche’ first appeared in a 1917 paper titled “The Niche Relationships of the California Thrasher” (Grinnell 1917). For author Joseph Grinnell, a niche was defined by both the habitat in which a species lives and its accompanying behavioural adaptations. It is not only part of the environment, he claims, but also a subset of the organism. The California thrasher’s form – short wings, strong legs – its camouflage, and its feeding behaviour are all inseparable from its chaparral habitat.

This builds on Darwin’s well-known observations on finches in the Galápagos, each having evolved in isolation – via ‘adaptive radiation’ – to fit local conditions. Ground finches have large beaks for seeds; tree finches, more delicate ones for insects or nectar. Morphologies in beaks, feet, and song co-evolved with niche requirements. “Natural selection,” Darwin wrote, “works silently and insensibly… at the improvement of each organic being in relation to its conditions of life” (Darwin 1859, 65).

Grinnell’s work was expanded by Charles Sutherland Elton, who shifted emphasis from morphology to function, redefining the ‘niche’ of an animal as “its place in the biotic environment, its relations to food and enemies” (Elton 2001, 64). In his book, Animal Ecology, Elton drew an analogy between species’ niches and jobs in a human community and emphasised co-evolution and adaptation, recognising the mutual shaping of species and environments.

Zoologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson further refined the concept with his idea of the “n-dimensional hypervolume”: a multi-dimensional space of environmental conditions and resources necessary for a species’ survival. While multiple species might occupy the same habitat, no two can occupy the same niche indefinitely. Hutchinson’s model returns to Grinnell’s emphasis on a species’ specific requirements, both biotic and abiotic (Hutchinson 1967). In 1967, Robert MacArthur and Richard Levins introduced the notion of “resource utilisation” to describe how similar species might coexist by partitioning resources, further extending the ecological precision of the niche concept (MacArthur and Levins 1967).

Psychologist James Gibson translated the concept into perceptual psychology: “Animal and environment make an inseparable pair. Each term implies the other,” he wrote (Gibson 1986, 8). Gibson also recognised that multiple animals could inhabit the same place, each perceiving a different “surrounding.” A related idea appears in Jakob von Uexküll’s notion of Umwelt – the world as it is experienced by a particular organism (Von Uexküll 1934). Rather than passively adapting, animals imbue environments with meaning through need-based perception. His example of a tick illustrates this: it responds only to light (to climb), mammalian smell (to drop), and skin (to burrow). Blind and deaf, the tick’s world consists of only these three triggers. The Umwelt is thus an abstraction, unique to the organism, shaped by action possibilities. Von Uexküll’s illustrations (by Georg Kriszat) attempted to depict these perceived worlds. One image shows the “environment” of a bee as a sensory abstraction from the fuller human-perceived “surroundings.” But these diagrams inevitably fall short of expressing the layered, memory-rich Umwelt of a non-human organism.

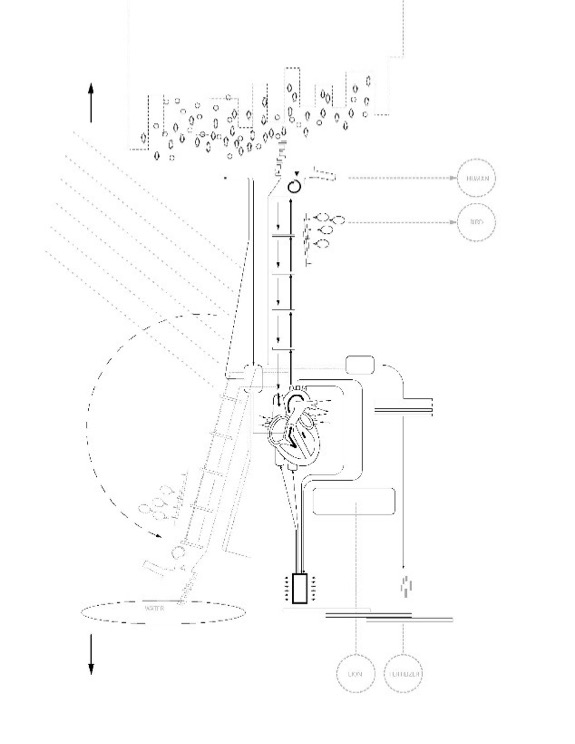

One can imagine the organism drawing in – whether literally including in its bubble of perception or metaphorically representing in its view of the world, the parts of the environment that are relevant to its survival. In this sense, the figure of the organism disappears. It is no longer an object; it is a mesh of systems and materials, both animal and environment.

Figure 2 [click to enlarge]. Giraffe Diagram. CODA, 2012. From Niche Tactics: Generative relationships between Architecture and Site, Routledge, 2015. The diagram rejects the figure of the giraffe in favour of a representation of the niche, which includes the organism and those parts of the environment essential to the animal’s survival

Figure 2 [click to enlarge]. Giraffe Diagram. CODA, 2012. From Niche Tactics: Generative relationships between Architecture and Site, Routledge, 2015. The diagram rejects the figure of the giraffe in favour of a representation of the niche, which includes the organism and those parts of the environment essential to the animal’s survival

This relationship between the organism and its context has clear parallels with developments in the field of architecture. Vernacular forms were adapted to their niches: Mexican adobe construction as a response to heat gain and thermal mass, the jigged entrances of the Scottish stone hut as a response to wind, the steeply pitched roofs of the Malaysian stilt-dwelling as a response to heavy rains and uncertain ground conditions. But for the last century, architecture has become increasingly disconnected from vernacular knowledge in favour of the homogenising aesthetics of Modernism.

In response to the rise of this “International Style,” a wave of “regionalism” surged up. In the 1960s, “Contextualism” arose in opposition to the persistent detachment from place seen in Modern design. Coined by Stuart Cohen and Steven Hurtt in 1965 at Cornell, the term described a design movement that derived from the surroundings of a building. R.E. Somol would later describe the movement as a rejection of the “internationalist utopia of nowhere” in favour of the “contextualist nostalgia for somewhere” (Somol 1992, 94).

At its best, Contextualism sought to harmonise buildings with their physical, cultural, and psychological settings. At its worst, it became a conservative exercise in imitation. As Cohen later lamented, it sometimes meant a “subservient repetition of the building next door,” amounting to renovation disguised as originality (Cohen 1974, 66). Colin Rowe admitted that Contextualism was often “radical middle of the road” (Rowe 1996, 2), while Mark Wigley decried it as “an excuse for mediocrity… for a dumb servility to the familiar” (Wigley and Johnson 1988, 17).

Critical Regionalism emerged as a more nuanced alternative. Coined by Alex Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre in the early 1980s, it rejected mimicry and pastiche while upholding “the individual and local architectonic features against more universal and abstract ones” (Tzonis and Lefaivre 1981, 15). Kenneth Frampton positioned the concept as a middle ground between a “high-tech” and a “compensatory” approach (Frampton 1983, 17) – a way to resist homogenization while avoiding nostalgia.

The debate continued into the twenty-first century, marked by books like Site Matters: Design Concepts, Histories and Strategies (Kahn and Burns 2004) and its 2021 follow-up (Kahn and Burns 2021) arguing for a physical and conceptual reengagement with site. With increasing focus on sustainability, architects were urged to treat the site as more than a surface or setting. Yet standard site analysis risks being overly generic. While it might capture shared habitat conditions, it rarely abstracts them into the differentiated experiential realities – i.e., niches – that contribute to new and original built form. That is, where the niche drives the form of the building more powerfully than other forces: aesthetic, financial, and so on.

The ecological niche, reintroduced through design, offers a critical framework for reshaping human-built environments as integrally responsive to the systems they inhabit. In both ecological and architectural terms, survival now depends not only on where we build, but how precisely we attune our materials, forms, and behaviours to the demands and limits of place.

In Niche Tactics: Generative Relationships between Architecture and Site (O’Donnell 2015), I argued for a return to an understanding of the architectural terms ‘site’ and ‘context’ not as generic conditions but as intimately tied to the ecological concept of the niche. A niche, I clarified, is not merely a position in space but a complex set of functional relationships – a dynamic between organism and environment defined by material flows, behaviours, and adaptations over time. For architecture, this clarification hoped to reorient how we consider design methodology: not as the imposition of form upon a site, but as the co-evolution of form and environment toward mutual accommodation. The standard site analysis, I argued, often operates at the level of habitat description – topography, climate, regulations – but ecologically speaking, this is akin to drawing up a general map of a biome while ignoring the many different species that live within it. Such analyses tend to produce generic building designs that could land on any similar topography but are deeply insensitive to the finer-grained, lived, and contested environmental conditions that define a true niche. In contrast, a niche-based design methodology would treat the building not as a foreign object but as an agent of its niche construction – an organism evolving in close dialogue with its surroundings, seeking light, water, space, temperature equilibrium, and social and ecological resonance. The resulting morphologies – perhaps awkward in places, even lop-sided or twisted – would signal adaptation, not deviation. These forms would emerge not from abstract formalism, but from the real, site-specific pressures of coexistence.

The niche, in this sense, demands attention to the ecotone – the transitional zone between ecosystems, where tensions, overlaps, and hybrid conditions foster biodiversity and transformation. The concept, first glimpsed in Alfred Russel Wallace’s early observations of species turnover across biogeographic boundaries (Wallace 1859), was later formalised by Frederic Clements (1904–5), who described ecotones as sites of intense ecological interaction and evolutionary pressure. Eugene Odum further advanced the idea by emphasising that ecotones are not just boundaries but zones of increased productivity, complexity, and exchange – ecological “edges” where energy and material flows often peak (Odum 1971).

In design terms, this means working in the messy, negotiated spaces between fixed systems: between building and climate, culture and topography, infrastructure and living systems. It means refusing simple boundaries. This resonates with the contemporary turn in architecture and beyond, toward understanding sites not as discrete containers but as relational fields. As Kent et al. (1997) argue, ecotones are also cultural interfaces, shaped by human activity as much as natural processes. Lloyd et al. (2000) extend this further, exploring anthropogenic ecotones – transitional landscapes generated by human intervention, such as urban-rural fringes or post-industrial edges – spaces that challenge conventional disciplinary boundaries but are increasingly central to design concerns.

This complexification and nuancing of the term is shared by recent works such as Niche Construction: The Neglected Process in Evolution (Odling-Smee, Laland, and Feldman 2003) and Environmental Evolution: Effects of the Origin and Evolution of Life on Planet Earth (Margulis, Matthews, and Haselton 2000). Both highlight how organisms do not merely adapt to environments: they actively reshape them. Beavers redirect rivers; corals build reefs; fungi cycle nutrients into new fertility. This reframing has powerful implications for architecture: buildings, too, alter their contexts materially and energetically, and they should be designed with that feedback loop in mind.

Such a shift also aligns architecture with the broader cultural and planetary imperative of sustainability, defined here as the capacity to create and build without depleting the ecological, social, or material systems on which life depends. Yet sustainability cannot be achieved by technical fixes alone. It must involve a transformation of worldview – a recognition that architecture participates in webs of interdependence and vulnerability. Niche-thinking offers a conceptual and formal route into such transformations. Designing with the niche means thinking with and like the natural world: specific, situated, responsive, and restrained.

Such methodologies have advanced well in other architecture-adjacent disciplines. McHarg, in Design With Nature (1969), advanced this ecological approach at the scale of the landscape. His “layer-cake” maps prefigured GIS systems by showing how geology, vegetation, hydrology, and human uses are interrelated – an early model of what we might now call niche cartography. McHarg’s brilliance lay in seeing cities and landscapes not as opposed, but as nested ecologies in mutual transformation.

In contemporary discourse, niche design converges with theories such as Science and Technology Studies (STS) and Actor-Network Theory (ANT), both of which reject linear causality and instead model phenomena as complex, dynamic assemblages. These frameworks resonate with the idea that architectural form emerges from entanglements – not just physical or environmental, but also cultural, political, and technological. In ANT terms, a building is not a finished object but a network in becoming, composed of actors both human and non-human: weather, materials, legislation, memory, insects, utilities, rituals, and more. In this expanded sense, the niche becomes a site of negotiation, where competing agencies shape – and are shaped by – form.

Some architectural practices today are beginning to reflect this ethos, embracing flexibility, mobility, and low-impact design not as compromises but as ecological virtues. In extreme or fragile environments, this can mean retreating, building less, or building to disappear. In the Arctic, Lateral Office’s Arctic Adaptations project designs mobile, seasonal infrastructure that responds to permafrost instability and Inuit mobility patterns. In Australia, Glenn Murcutt’s houses tread lightly – single-story, narrow plans with operable louvres and water-harvesting roofs – highly specific to place and climate. Similarly, Shigeru Ban’s Paper Log House, designed for post-disaster contexts, exemplifies low-tech, mobile niche-making: recyclable, rapidly deployable, adapted to local materials and needs. In contrast to heavy, permanent structures, Ban’s work embodies ephemeral specificity – durable enough to last through a crisis, light enough to yield to the next phase of life.

At the frontier of this thinking is Anna Heringer’s METI Handmade School in Bangladesh, built from mud and bamboo, using traditional techniques and community labour. This building does not merely occupy its niche – it strengthens it. The presence of the school supports local craft, sustains cultural identity, and improves environmental resilience through passive cooling and regenerative materials. It is a building that teaches as it shelters.

In my work, Party Wall at MoMA PS1 (CODA 2013) functioned as a prototype for architectural reuse and transformation. Constructed from leftover skateboard manufacturing byproducts, the structure reimagined waste as a design input while also responding climatically: it cast shade, caught breezes, and channelled activity. Other projects, such as Evitim (OMG 2017), (Figure 3), Tripe (CODA 2018), and Goosebumps (CODA 2016) engage in various ways with the use and pre-design of waste in order to provoke thinking around issues of waste and reuse (O’Donnell and Pranger 2019).

More recently, the work began to engage in time-based work that understood architecture as a process of entropy, degeneration, growth, and action. Primitive Hut (OMG! 2016) is a small structure made of woven willow that explores temporal and material ephemerality, allowing the building to decay, adapt, and be reborn seasonally (Figure 4). Zimmer (OMG 2015) is a physically dynamic structure that uses Chebyshev locomotion to relocate itself around a site seasonally (O’Donnell and Ibarra 2022). These works advance niche architecture not only as a theory but as a materially inventive and socially attuned practice, demonstrating how buildings might operate as adaptive agents in ongoing dialogue with their environments and communities.

These examples suggest that designing with the ecological niche does more than shift aesthetic or performative criteria: it restructures our very understanding of what buildings are, how they endure, and whom or what they serve. Niche architecture is not a metaphor. It is a rigorous, generative framework for engaging environmental, cultural, and temporal specificity toward a mode of dwelling that aligns with forms of life, rather than displacing them.

Contemporary theoretical biology offers a fertile ground for extending the ecological conception of architectural niche beyond the contemporary built examples and into the future of the role of the niche for architecture. The work of Brian Goodwin and P.T. Saunders in Theoretical Biology: Epigenetic and Evolutionary Order from Complex Systems (Goodwin and Saunders, 1992) provides a framework for understanding how form and function emerge from self-organising systems. Rather than viewing organisms as passive responders to static environments, Goodwin and Saunders show that morphogenesis – the development of form – is an active, generative process shaped by both genetic and environmental dynamics. This resonates deeply with an architectural approach that treats form not as imposed but emergent, where buildings unfold in dialogue with complex site-specific factors. Similarly, in Francisco Varela’s Principles of Biological Autonomy (Varela 1979), the notion of autopoiesis – or self-organisation – suggests a way of thinking about architecture not as a fixed object, but as a dynamically regulated system, always engaged in processes of material exchange, regulation, and adaptation.

Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb’s Evolution in Four Dimensions (Jablonka and Lamb 2014) further expands the field by incorporating epigenetic, behavioural, and symbolic inheritance into our understanding of evolution. Their model suggests that evolutionary trajectories are shaped not only by genes but by the learned behaviours and material-cultural scaffolds that organisms engage with. In architectural terms, this opens a pathway to thinking about how buildings ‘inherit’ design logics, material affordances, and situated behaviours – how they become cultural actors in a broader evolutionary ecology. Horst Hendriks-Jansen’s Catching Ourselves in the Act (Hendriks-Jansen 1996) similarly bridges the cognitive and the ecological. His account of interactive emergence and situated activity supports a design logic where buildings are not seen as discrete artefacts but as part of assemblages that include human actions, social routines, environmental processes, and technological systems. This resonates strongly with the relational ontologies of Science and Technology Studies (STS) and Actor-Network Theory (ANT), where entities – including buildings – gain form and function through their positions in dynamic networks.

In this view, niche architecture might be considered not just responsive to ecological conditions but participating in the ongoing constitution of those conditions, helping shape the very networks of activity, exchange, and meaning in which it is embedded.

Taken together, these works help articulate a vision of architecture not as a fixed intervention but as an evolving participant in co-constructed environments. Buildings conceived within this framework are not designed for a static context but with a living, changing one. This conceptual shift has profound implications for sustainability, considered not merely as the minimisation of environmental impact, but as the capacity to maintain and regenerate life-sustaining relationships across time. A niche-based architecture, drawing from these theoretical insights, emphasises fit, adaptability, responsiveness, and transience. It advocates for structures that may move, adapt, or decay; that engage in feedback loops with their surroundings; and that learn or evolve as part of larger systems (Figure 6). This is not a call for architecture to recede from interconnectedness, but for it to engage more deeply – and yet with more focus – with the shifting, networked, and emergent nature of life itself.

References

Burns, Carol J., and Andrea Kahn, eds. 2004. Site Matters: Design Concepts, Histories and Strategies. London: Routledge.

Clements, Frederic E. Research Methods in Ecology. Lincoln: University Publishing Company, 1905.

Cohen, Stuart. 1974. “Physical Context/Cultural Context: Including It All.” In Oppositions Reader, edited by K. Michael Hays, 66. Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press.

Darwin, Charles. 1859. On the Origin of Species, 6th ed. Stilwell, KS: Digireads Publishing, 2010.

Dussault, A. C. 2022. “Functionalism without Selectionism: Charles Elton's ‘Functional’ Niche and the Concept of Ecological Function.” Biological Theory 17: 52–67.

Elton, Charles S. 2001. Animal Ecology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Frampton, Kenneth. 1983. “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance.” In Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, 16–30. San Francisco: Bay Press.

Gibson, James J. 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Goodwin, Brian C., and P. T. Saunders. 1992. Theoretical Biology: Epigenetic and Evolutionary Order from Complex Systems. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Grinnell, Joseph. 1917. “The Niche-Relationships of the California Thrasher.” The Auk 34 (4): 427–433.

Hadley, E. A. 1997. “Evolutionary and Ecological Response of Pocket Gophers (Thomomys talpoides) to Late-Holocene Climatic Change.” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 60.

Hendriks-Jansen, Horst. 1996. Catching Ourselves in the Act: Situated Activity, Interactive Emergence, Evolution, and Human Thought. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hutchinson, G. E. 1957. “Concluding Remarks.” Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology 22: 415–427.

Jablonka, Eva, Marion J. Lamb, and Anna Zeligowski. 2014. Evolution in Four Dimensions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kent, M., P. Coker, and A. Field. Vegetation Description and Analysis: A Practical Approach. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1997.

Lefaivre, Liane, and Alexander Tzonis. 1981. “The Grid and the Pathway: An Introduction to the Work of Dimitris and Susana Antonakakis.” Architecture in Greece 5: 15.

Lefaivre, Liane, and Alexander Tzonis. 2003. “Critical Regionalism: A Facet of Modern Architecture since 1945.” In Critical Regionalism: Architecture and Identity in a Globalized World. New York: Prestel.

Lloyd, A. M., P. E. Gadd, and J. A. van den Bergh. “Anthropogenic Ecotones: Human-Influenced Transitions and Their Implications for Conservation.” Landscape and Urban Planning 48, 3–4 (2000): 215–233.

Lomolino, Mark V., Brett R. Riddle, and James H. Brown. 2006. “Single Species Patterns.” In Biogeography, 2nd ed., 111–142. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

MacArthur, R., and R. Levins. 1967. “The Limiting Similarity, Convergence, and Divergence of Coexisting Species.” American Naturalist 101 (921): 377–385.

Margulis, Lynn, Clifford N. Matthews, and Aaron Haselton. 2000. Environmental Evolution: Effects of the Origin and Evolution of Life on Planet Earth, 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mumford, Lewis. 1947. “Skyline.” New Yorker, October 1947.

O’Donnell, Caroline. 2015. Niche Tactics: Generative Relationships Between Architecture and Site. New York: Routledge.

O’Donnell, Caroline and Ibarra, José, eds. 2022. Werewolf: The Architecture of Lunacy, Shapeshifting, and Material Metamorphosis. San Francisco: AR+D/ORO Publications.

O’Donnell, Caroline and Pranger, Dillon, eds. 2019. The Architecture of Waste: Design for a Circular Economy. New York: Routledge.

Odum, Eugene P. Fundamentals of Ecology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 1971.

Oë, Alva. 2004. Action in Perception. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Odling-Smee, F. John, Kevin N. Laland, and Marcus W. Feldman. 2003. Niche Construction: The Neglected Process in Evolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rowe, Colin. 1996. As I Was Saying: Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays. Vol. 3, edited by A. Carragone. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schluter, Dolph. 2000. The Ecology of Adaptive Radiation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, M. F., and J. L. Patton. 1988. “Subspecies of Pocket Gophers: Causal Bases for Geographic Differentiation in Thomomys bottae.” Systematic Zoology 37: 163–178.

Somol, R. E. 1992. “Speciating Sites.” In Anywhere, edited by Cynthia Davidson, 92-97. New York: Rizzoli.

Varela, Francisco J. 1979. Principles of Biological Autonomy. New York: North Holland.

von Uexküll, Jakob. 1934. “A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men: A Picture Book of Invisible Worlds.” In Instinctive Behavior: The Development of a Modern Concept, edited and translated by Claire H. Schiller, 5–80. New York: International Universities Press.

Wallace, Alfred Russel. On the Law Which Has Regulated the Introduction of New Species. London: John Van Voorst, 1855.

Wigley, Mark, and Philip Johnson. 1988. Deconstructivist Architecture: The Museum of Modern Art. New York: Little Brown.