Mapping

Katja Garson

Related terms: cartography, more-than-human, multispecies, navigation, place, representation, situated knowledge

Mapping can be described as a form of sense-making and communication. It is the translation of lived experience, observations, ideas and predictions into a curated and ordered form. Within the often visual representations which we call maps, different elements are connected across a landscape or terrain and certain colours and shapes are given symbolic meaning. The practice of mapping frequently comes about due to the desire to understand or navigate physical places and spaces. Any number of things in the ‘real world’ might be mapped, from transport connections to national parks. However, one might also map out thoughts as a ‘mind-map’ or create a ‘road-map’ of possible future steps in a process.

Maps are sometimes seen as comprehensive and taken-for-granted depictions of a location, phenomenon or area of thought. Within diagrammatic thinking, maps are seen as a cartographic form of diagram-creation in which elements are placed together in connection with one another in an effort to represent structural elements of the real world, to illustrate the overlaps and relations between concepts, or to consider how things might be otherwise (Gerner 2010). Important work has been done by critical cartographers, feminist geographers, and decolonial scholars, among others, to challenge the view of maps as definitive, all-encompassing and apolitical (Nash 1994; McGurk and Caquard 2020). Who does the mapping, how they do it and why is informed by subjective desires and selective ways of seeing the world (Pavlovskaya and St Martin 2007). Mapping, both historically and in the present day, has been a practice of domination and control (Simpson 2021). Swedish (and more generally Scandinavian) expansion into the apparently ‘empty’ lands of Sápmi (De Leeuw 2023; Ojala and Nordin 2019) and British and Dutch tea-plantation cartography (Karlsson 2022) are just a couple of examples.

Forms of mapping which appear to transcend political boundaries are also embedded in unequal power relations. For example, international satellite mapping promotes a ‘God’s eye’ view of the world (Haraway 1988), and is done by government agencies and private actors who hold the data and control its use (Bennett et al. 2022; Lindberg 2019). Furthermore, no phenomenon or place is ever entirely stationary, and many things, for instance, sea ice (Shake et al. 2018) or the spread of an infectious disease (Dawson et al. 2015), are overtly mobile. Trying to map such things is difficult. Even real-time digital approaches and predictive computer models must grapple with technological challenges and gaps, legal barriers, and human error (Kraemer et al. 2016). For instance, the use of cell-phone data may be limited to high-income user groups, meaning that using this data for mapping human mobility and the spread of disease results in a map which applies only to certain demographics and corridors of movement dictated by the use of particular transport links (Wesolowski et al. 2014). Mapping, therefore, only ever captures a small slice of a moment in the story of a place or phenomenon.

New ways of thinking about maps and map-making are emerging within environmental humanities research. These extend pre-existing critiques and also raise new points about lived experiences and research processes within contexts of intertwined social, political, and ecological challenges. Although the issues of representation and ‘unfinishedness’ remain, they are increasingly accepted as part of what it is ‘to map’, just as they are part of what it is to live in a complex multispecies world. Creative approaches to mapping have proliferated in response to challenges such as the coronavirus pandemic and the impacts of climate change. Mapping has been used to express personal spaces, feelings, and local- and intimate-level experiences which offer more nuance than the sanitised or reductive maps produced by official bodies (Pase 2021). Sometimes, mapping has been used as a tool of conscious dissent and protest. Mapping has also moved beyond a purely visual focus to include senses such as sound (Duggan and Gutiérrez-Ujaque 2025) and smell (Perkins and McLean 2020).

It is worth noting the notion of ‘deep mapping’, which has gained traction in the ‘spatial humanities’. Deep mapping suggests that places be analysed with attention to depth, rather than only looking at what is on the surface. It engages with depth not only in terms of literally digging down through floorboards, earth, silt and rocks, but also in terms of cultural history and memory, producing insights into more intangible temporal layers and stories across generations. Deep mapping is performative and allows mappers to “immers[e] themselves in the warp and weft of a lived and fundamentally intersubjective spatiality” (Roberts 2016, 6). Bodenhamer et al. (2013, 5) write that, “framed as a conversation and not a statement, deep maps are inherently unstable, continually unfolding and changing in response to new data.” This kind of mapping does not lead to an easily utilised ‘field map’; rather, the experience of deep mapping and being attentive to place is perhaps more important than the end product (Roberts 2016).

Alongside these developments, there is still so much potential in thinking through what mapping could or should involve within an environmental humanities context. What could mapping be when we consider addressing intertwined socio-environmental challenges with methods and approaches from across the humanities and social sciences? In particular and firstly, I suggest that there is space for greater acknowledgement of nonhumans and the material world as collaborators and shapers of maps. To assume that mapping is a purely human affair is to ignore the life-worlds of beings other than human, which shape the world around us and which experience – and map – the same world in many different ways. There are some recent examples in which researchers and artists have opened up to multispecies perspectives and nonhuman map-making collaborators: Krug et al. (2023) explore how gardening with the plant Silphium integrifolium reveals the multiple scales at which a single species has an impact or may be silenced, from local garden-plot scale to wider industrial scales; Mathews (2018) ‘reads’ and walks with ancient trees, their twisted limbs and positions in the landscape providing an understanding of historical multispecies relations within the region.

Secondly, as alluded to within conversations on deep mapping and a turn towards memories and stories within map-making, mapping may be understood as a cross-temporal endeavour: Traditional maps struggle with the problem of capturing a context and freezing it in time, but alternative forms of mapping might play with ephemerality and constant change. Although there is much talk within the environmental humanities on themes of extinction, loss, futures and other change-related terms, few researchers have delved into their intersections with map-making. One exception is the creative project ‘Mapping Extinction’ (Knight 2023). In an article about this project, Knight (2023) describes the ‘inefficiency’ of pulling together recordings and photographs from different time periods and then attempting to map species’ bodily movements and the wider loss of life. However, this difficulty can also be seen as illustrative of the times in which we live, since “the processes of drawing within inefficient mapping facilitate data that is nonrepresentational in that they attend to the excessive and difficult-to-describe conditions of ecological catastrophe and speculative in that the images are visualising possible future scenarios” (Knight 2023, 23).

As an artistic project, ‘Mapping Extinction’ overlaps with a third promising area of work on mapping within the environmental humanities. As mentioned earlier, creative and activist mapping is already well-established within spaces outside of academia and is being studied within disciplines such as anthropology and human geography. ‘Counter-mapping’, in which different artistic styles and mediums are used, contests normalised though often unjust ways of perceiving, organising and representing locations or issues (Duggan and Gutiérrez-Ujaque 2025). Alternative maps may be produced to highlight what is usually hidden, or to suggest how things could be different. I believe that activist or protest mapping holds promise for highlighting desires, concerns and aims within the environmental humanities. To name only one example, imagine a map of a polluted urban waterway co-created by water scientists, ecologists, kayakers, artists, and aquatic flora and fauna. Perhaps such a map would be more effective in convincing policy-makers and city planners that change is needed than a signed letter or statistics alone.

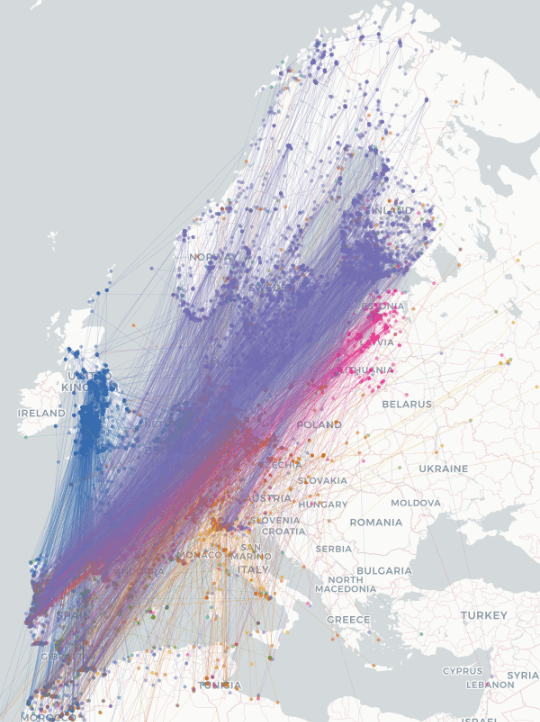

As I write this piece in June 2025, I have been following the daily activities of two pairs of European pied flycatchers. Watching them dart in and out of their nest-boxes intrigued me. Where did they come from, I wondered, and where will they be when winter comes? An online ‘migration atlas’ map (EURING/CMS, n.d.) of the migratory routes taken by flycatchers across North Africa, Europe, and the Middle-East shows a dense cross-hatch: continents and countries are dissected by coloured lines representing the movements of 7031 individual birds (fig. 1). Each line connects two or more points which correspond to locations in which the same individual bird was found or captured. Generally, European pied flycatchers spend the summer in northern and central Europe, and fly to the Mediterranean and North Africa for the winter. The records contributing to the map span a century from 1918 to 2018, though some years do not feature in the map. The map contains only artificially straight lines; what happens between the two ‘contact points’ is not truly covered.

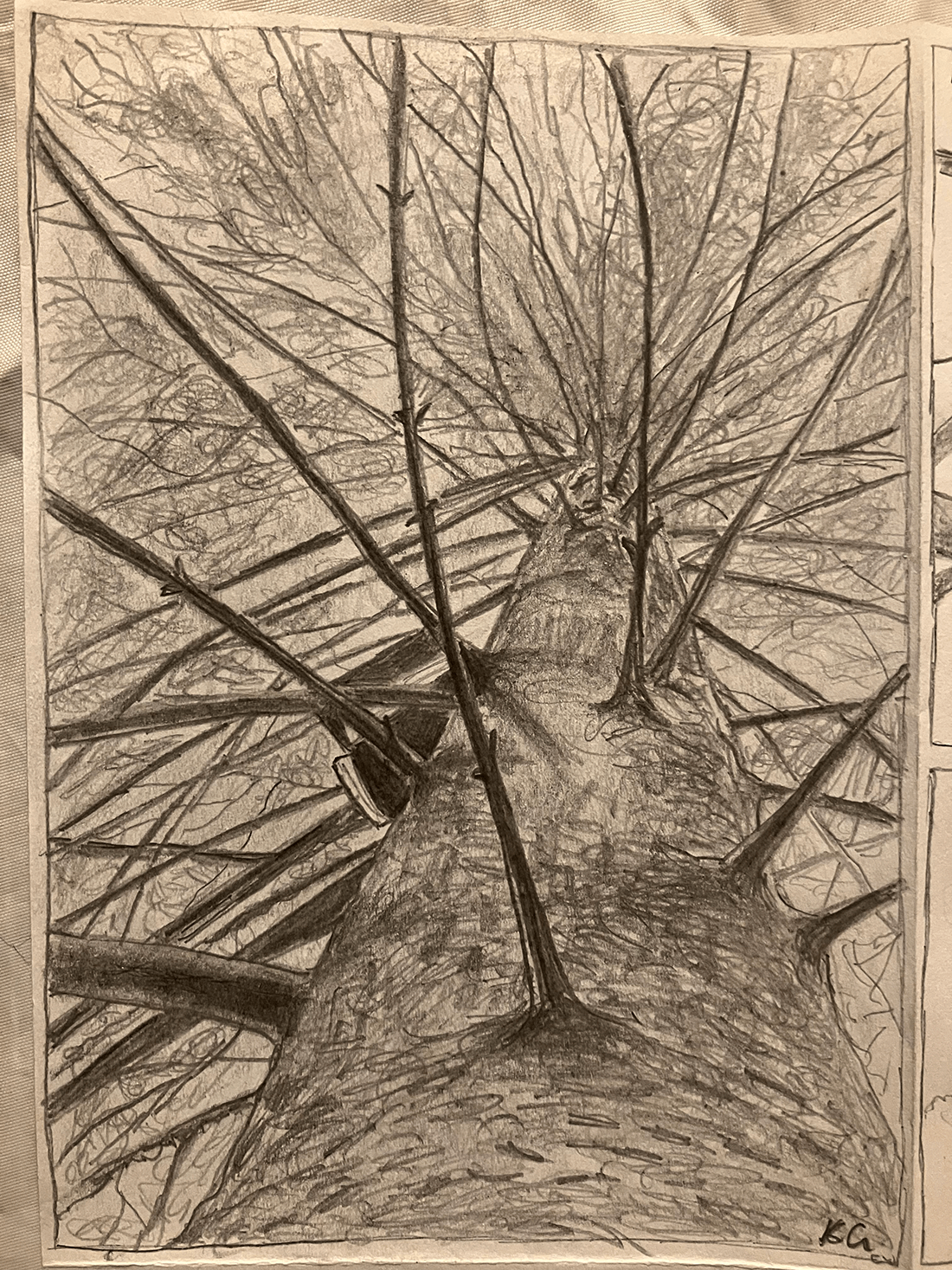

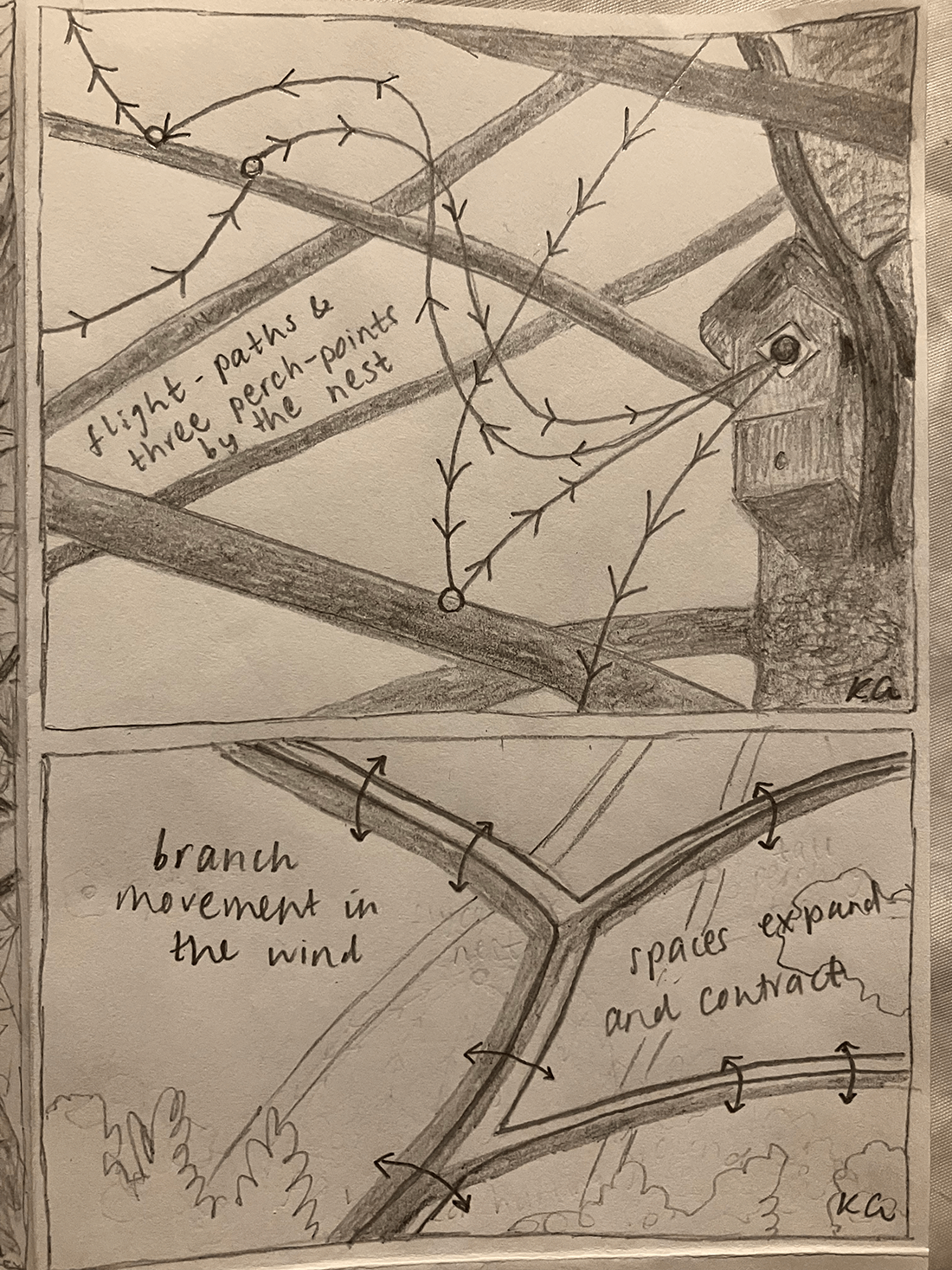

Following the flycatchers at a local scale has allowed me to become acquainted with individual families of birds, and their daily flightpaths between their hunting grounds and their nest boxes have gradually become apparent. By paying attention to the flycatchers’ activities, I have developed a new understanding of the landscape around me. My awareness of the trees and terrain now incorporates trying to sense like a flycatcher. Mapping this place with flycatchers means building up a knowledge of the locations of comfortable perching branches, of fly- and caterpillar-hideaways, of the movements needed to hop from branch to branch and into the nest-box, and of patches of air of many different shapes, volumes and velocities. I took some time to draw the spruce holding the nest-box, as well as observing the birds’ movements nearby (figs. 2-3). Attempting to represent this new situated knowledge was tricky: branches move, birds vary their behaviours based on conditions and time of day, and above all else, trying to draw ‘as a bird sees’ is almost impossible when observing only through the human eye.

I wonder, then, about the mapping being done by flycatchers and other species. Researchers have shown that many migratory birds follow man-made infrastructures such as major roads, and that birds and mammals alike rely on memory as well as on in-the-moment perception to find their way (Bracis and Mueller 2017; Gu et al. 2021). How, then, do flycatchers and other species make sense, spatially and temporally, of the world around them? Is their world an ever-unfolding map, never represented in a way that we could imagine, but held in their minds and collective memory? How does their mapping respond to changes in climate and the environment, and to things which shift suddenly or slowly? What senses might be dominant? And how can being attentive to other senses, lifeworlds, and ways of organising information help to find solutions in contexts of socio-environmental controversy or tension? Answers to these questions may be given, to an extent, by scholars working in ecology and biology. Others may remain a mystery, since “nonhuman perspectives appear unreachable for humans – we cannot adopt the perspective of, for example, a microbe” (Lopez et al. 2025, 11). Still, asking such questions contributes to ongoing efforts to engage differently – with more care and attentiveness (Krzywoszynska 2019) – with places, spaces and phenomena.

Although the utility of traditional maps as instruments for reaching a destination cannot be denied, there is a need to consider creative, experimental, sensed, cross-temporal, and multispecies mappings. This comes from an overall movement within the environmental humanities to highlight and counter extractive, colonial, imperialist, reductive, and dualistic thinking. Navigating a city based on the locations of certain plants or making note primarily of sounds or textures can also quite simply be enjoyable and provides a sense of going against the grain. Given today’s ecological and social challenges, mapping can and arguably should be a tool for increased care and the expression of diverse stories and accounts. This imperfect and complicated world invites mapping outside the box; mapping as a dance across multiple temporalities with multispecies collaborators.

References

Bennett, Mia M., Janice K. Chen, Luis F. Alvarez Leon and Colin J. Gleason. 2022. “The politics of pixels: A review and agenda for critical remote sensing.” Progress in Human Geography 46 (3): 729-752.

Bodenhamer, David J., Trevor M. Harris and John Corrigan. 2013. “Deep mapping and the spatial humanities.” International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 7 (1-2): 170-175.

Bracis, Chloe and Thomas Mueller. 2017. “Memory, not just perception, plays an important role in terrestrial mammalian migration.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284 (1855): 20170449.

Dawson, Peter M., Marleen Werkman, Ellen Brooks-Pollock and Michael J. Tildesley. 2015. “Epidemic predictions in an imperfect world: modelling disease spread with partial data.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282 (1808): 20150205.

De Leeuw, Georgia. 2023. “The virtue of extraction and decolonial recollection in Gállok, Sápmi.” In Coloniality and Decolonisation in the Nordic Region, edited by Adrián Groglopo and Julia Suárez-Krabbe, 68-88. Routledge: London.

Duggan, Mike and Daniel Gutiérrez-Ujaque. 2025. “Counter-mapping as praxis: Participation, pedagogy, and creativity.” Progress in Human Geography: 03091325251348610.

EURING/CMS. n.d. The Eurasian African Bird Migration Atlas: “European pied flycatcher: Ficedula hypoleuca”. Available at: https://migrationatlas.org/node/1804. Accessed 28.06.2025.

Gerner, Alexander. 2010. “Diagrammatic Thinking.” In Atlas of Transformation, edited by Zbynek Baladran and Vit Havranek (Prague: Tranzit, 2010), 173-184; available online: http://monumenttotransformation.org/atlas-of-transformation/html/d/diagrammatic-thinking/diagrammatic-thinking-alexander-gerner.html.

Gu, Zhongru, Shengkai Pan, Zhenzhen Lin, Li Hu, Xiaoyang Dai, Jiang Chang, Yuanchao Xue et al. 2021. “Climate-driven flyway changes and memory-based long-distance migration.” Nature 591 (7849): 259-264.

Haraway, Donna. 1988. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599.

Karlsson, Bengt G. 2022. “The imperial weight of tea: On the politics of plants, plantations and science.” Geoforum 130: 105-114.

Knight, Linda. 2023. “Inefficiently mapping extinction: A research-creation, practice-led approach to visualising biodiversity loss.” Research in Education 117 (1): 11-25.

Kraemer, M.U., S.I. Hay, D.M. Pigott, D.L. Smith, G.W. Wint, and N. Golding. 2016. “Progress and challenges in infectious disease cartography.” Trends in parasitology 32 (1): 19-29.

Krug, Aubrey Streit, Ellie Irons and Anna Andersson. 2023. “Sensing scale in experimental gardens: un-lawning with Silphium civic science.” Ecozon@: European Journal of Literature, Culture and Environment 14 (1): 99-118.

Krzywoszynska, Anna. 2019. “Caring for Soil Life in the Anthropocene: The Role of Attentiveness in More-Than-Human Ethics.” Trans Inst Br Geogr 44: 661–675.

Lindberg, Helena G. 2019. “The constitutive power of maps in the Arctic.” Doctoral dissertation. Lund University, Sweden.

Lopez, Paula Palanco, Anna Krzywoszynska and Agnese Bankovska. 2025. “Towards More-Than-Human Negotiation: Constructing Contact Zones with Nonhuman Beings.” Suomen Antropologi: Journal of the Finnish Anthropological Society 49 (2): 5-18.

Mathews, Andrew S., 2018. “Landscapes and throughscapes in Italian forest worlds: thinking dramatically about the Anthropocene.” Cultural Anthropology 33 (3): 386-414.

McGurk, Thomas J., and Sébastien Caquard. 2020. "To what extent can online mapping be decolonial? A journey throughout Indigenous cartography in Canada." The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 64 (1): 49-64.

Nash, Catherine. 1994. Remapping the body/land: new cartographies of identity, gender, and landscape in Ireland, Chapter 10. In: Writing women and space: colonial and postcolonial geographies. Edited by Alison Blunt and Gillian Rose. 227–250. New York: Guilford Press.

Ojala, Carl-Gösta and Jonas Monié Nordin. 2019. “Mapping land and people in the north: Early modern colonial expansion, exploitation, and knowledge.” Scandinavian Studies 91 (1-2): 98-133.

Pase, Andrea, Laura Lo Presti, Tania Rossetto and Giada Peterle. 2021. “Pandemic cartographies: a conversation on mappings, imaginings and emotions.” Mobilities 16 (1): 134-153.

Pavlovskaya, Marianna, and Kevin St Martin. 2007. "Feminism and geographic information systems: From a missing object to a mapping subject." Geography compass 1 (3): 583-606.

Perkins, Chris, and Kate McLean. 2020. “Smell walking and mapping.” In Mundane methods, edited by S. M. Hall and H. Holmes, 156-173. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Roberts, Les. 2016. “Deep mapping and spatial anthropology.” Humanities 5 (1): 5.

Shake, Kristen L., Karen E. Frey, Deborah G. Martin and Philip E. Steinberg. 2018. “(Un)frozen spaces: Exploring the role of sea ice in the marine socio-legal spaces of the Bering and Beaufort Seas.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 33 (2): 239-253.

Simpson, Thomas. “Cartography and empire from early modernity to postmodernity.” In The Routledge Handbook of Science and Empire, edited by Andrew Goss, 21-34. Milton Park: Routledge, 2021.

Wesolowski, Amy, Caroline O. Buckee, Linus Bengtsson, Erik Wetter, Xin Lu and Andrew J. Tatem. 2014. “Commentary: Containing the Ebola outbreak-the potential and challenge of mobile network data.” PLoS currents 6 (September 29): ecurrents-outbreaks.