Landscape

Bror Axel Dehn and Lila Lee-Morrison

Related terms: background, positionality, extractivism, data, anthropocene, media, aesthetics, nonhuman, scale

This entry on the term “landscape” provides a brief overview of how evolving representational practices in both literature and art are reinvigorating the genre against the backdrop of multiple epistemic shifts in relation to the environment. This includes the naming of a new era of the Anthropocene, climate crises, postcolonial scholarship, indigenous knowledge, networked technology, and shifting scales of temporality and spatiality. Thus, this analysis attends to how landscape operates as a cultural practice not merely in ways that signify or symbolise power relations but also as an agent of power itself: an agent that is both independent of human intention or use and a possible medium of expression of nonhuman intelligences (Mitchell 2002, 2, 5).

–scape / –scope

In Western cultural history, landscape has encompassed a range of meanings across various fields of study. Since the Renaissance, it has primarily referred to the artistic depiction of natural scenery as viewed from the vantage point of a detached observer (Cosgrove 1984, 9). Rooted in the Scientific Revolution, this notion of landscape was enabled by the emergence of modern artistic techniques like linear perspective, which helped consolidate a dualistic worldview: Within this paradigm, which geographer Kenneth Olwig (1996) has termed the scenic landscape, nature is imagined as an object of aesthetic contemplation. As Olwig notes, however, such an idea of landscape rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of its etymological roots. Drawing on the Old Norse usage of the word, where “-scape” implies material reality rather than the purely visual scope associated with the Greek skopein, Olwig formulates the idea of the substantive landscape: a physical environment shaped by natural processes as well as human and nonhuman activity.

The anthropologist Tim Ingold (2011, 126) makes a similar distinction when he points out that the term landscape, in its early medieval provenance, originally referred to the shaping of the land through cultivation and conditions of farming and agricultural practices. As Ingold describes, medieval shapers were farmers, not painters, “whose purpose was not to render the material world in appearance rather than substance, but to wrest a living from the earth.” In this sense, both Olwig and Ingold critique the conflation of -scape with -scope in shaping our contemporary understanding of landscape. This is pertinent in consideration of a nuanced understanding of -scope as incurring an agential role in representation, especially within visual culture and film theory and its conceptual expansion of a scopic regime, recognising the cultural, technical and historically specific aspects which construct and supplant that which is being represented (Metz 1982, 61, Jay 1998). Notwithstanding this, this entry looks at some of the ways representations of landscape in contemporary literature and art reclaim the original notion of -scape in addressing various forces and agencies that are implicated in the active shaping of land. As a more encompassing notion for the following discussion, we adopt Anna Tsing’s (2024, 152) formulation that landscape be understood as “the sedimentation of human and nonhuman activity, which, taken together, creates places. Landscape is a busy intersection of contemporary action entangled with the traces of previous action. Because it offers signs of the past, the landscape is amenable to archival practices. Landscape is not just an archive, but one can do archival readings on a landscape.” Thus, we suggest how landscape representation could be generative of meaning at this crossroads of -scape and -scope, especially in relation to a notion of landscape as a layered and dynamic site shaped by the interaction of human and nonhuman activities over time.

Positionality

An aspect that frames historical traditions of landscape representation and also stands out in contemporary discourse of environmental aesthetics is a shift in attention towards the cultural implications of positionality. As a general expression of the modern attempt to dominate nature, the scenic understanding of landscape as the backdrop to human events has influenced both literary and artistic forms. As Bruno Latour (2016, 19) observes, this perspective places the viewer in “the place of nowhere,” a position removed from the material conditions of the landscape, which is treated as a pure scenography for human drama. In The Great Derangement (2016), Amitav Ghosh argues that the distinction between foreground and background has been central to the development of the modern novel. In particular, he critiques the realist mode of representation, which is typically defined by a set of generic conventions such as a plot that unfolds over a limited time span, a small cast of characters, and an emphasis on their psychological development. According to Ghosh, such a framework is incapable of addressing the narrative demands of the current era, where escalating ecological crises bring into focus the agency of nature within historical processes. Ghosh’s critique draws on Latour’s argument in Facing Gaia (2017), where the ecological crisis is described as a “mutation in our relationship with the world” (Latour 2017, 8): a perspectival shift in which nature should no longer be seen as a stable background but as a dynamic force in reciprocal relation with anthropogenic processes.

Similarly, in Western European art history and in paintings before the 19th century, landscape primarily acted as a backdrop to the subject of historical events. In contrast, East Asian traditions of landscape painting, dating back to the 14th century and produced within the context of the philosophical tenets of Taoism, positioned nature and environment as existing in the foreground. In this sense, the landscape was both the subject and the object of the artwork. These shifts in the positionality of landscape in art mirror what art historian Rachel Ziady Delue (2007, 11), in describing its role as part and parcel to human activity, has theorised as “apositional”, where landscape is understood as “neither foreground nor background, centre nor periphery.” This lack of a fixed position also suggests a sense of its omnipresence and as such, reflects the relational dynamics of what philosopher Timothy Morton (2013) elaborates on in their theory of hyperobjects, in that issues of scale and the increased development of computational tools for environmental measurement expand our knowledge of phenomena such as climate change and deep time, both of which exceed human perception. As Morton argues, this knowledge is primarily characterised by a positionality where humans no longer find themselves standing outside of the objects of scientific inquiry (as in the stance and site of objectivity) but rather deeply entangled within them. Considering this, landscape and its apositionality acquires a similar dynamic, loosening a fixed position and instead enveloping the observer, simultaneously existing as both “a subject of analysis, as well as the thing we live in” (Morton 2013, 17).

These differences in positionality seem central to thinking with when addressing the genre of landscape as an aesthetic practice in literary and artistic forms. In other words, a reconfigured understanding of nature as a dynamic force implies a departure from the notion of the scenic landscape and instead necessitates aesthetic forms that recognise a reciprocity between humans and their environments. Within this context, Ghosh (2016) argues that the climate crisis is a crisis of the imagination: it reveals a representational failure in traditional artistic forms. In a similar vein, literary scholars Eva Horn and Hannes Bergthaller (2019, 102) have noted of the many challenges in confronting the Anthropocene a major one concerns its aesthetic representation, requiring more than thematic engagement: it demands formal innovation. They point out that the changed ways of being in the Anthropocene arise from a shift in the position of the human in relation to the environment, which specifically involves a need to decenter the human perspective and the ability to aestheticize issues of latency, defined as “the withdrawal from perceptibility and representability,” entanglement, defined as “a new awareness of coexistence and immanence,” and scale, defined as “the clash of incompatible orders of magnitude” (Horn and Bergthaller 2019, 102). In other words, aesthetic forms capable of addressing these dimensions should therefore disrupt conventional modes of representation by offering new narrative strategies. The following sections will consider both contemporary literary and artistic practices that engage with these dimensions through their formal expression.

Contemporary Literature

Contemporary literature provides several instances of narrative strategies that respond to the challenges posed by the ecological crises. While a comprehensive account is beyond the scope of this section, a few illustrative examples are worth mentioning. In Chernobyl Prayer (1997), Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich uses a polyphonic form to present a chorus of voices bearing witness to the aftermath of a nuclear disaster. The structure of the book can be read not only as an expression but also as a formalisation of a landscape in which the human gaze has been radically decentered. The voices do not describe sublime experiences of nature from an elevated or neutral perspective. Rather than transcendental subjects, they appear as beings that are exposed on multiple scales simultaneously: as citizens of a nation, as organisms representing a species, and as vulnerable bodies within natural forces. In this altered perspective, the distinction between foreground and background, human and nonhuman, becomes problematic. This shift in perspective is registered through attention to the behaviour of animals: cows refuse to drink from contaminated water, bees remain inside their hives, and cats avoid the dead mice scattered across the fields. In this sense, the radiated landscape becomes more than a simple backdrop for human events but the very condition that defines both human and nonhuman engagement with the world.

In Rombo (2022), German writer Esther Kinsky similarly recounts the devastation of two earthquakes in northeastern Italy through a polyphonic prose that weaves together the human and the nonhuman in order to give voice not only to the survivors of the catastrophe, but also to the landscape and its various elements. Like Alexievich, Kinsky’s documentary style reflects a formal attempt to transgress the limits of a realist mode of representation in its implicit refusal to isolate human psychological experience from the landscape. Thus, in an interview, Kinsky says that her writing “has more to do with my idea of text and texture than with story. There are no plots and there’s no narrative arc in terms of suspense or closure.” (Foster 2024)

German writer W.G. Sebald presents a different yet equally interesting approach to landscape in The Rings of Saturn (1995). A hybrid of travelogue, memoir, and historical essay, this uncategorizable book of prose offers a melancholic meditation on landscape as a palimpsest of different entangled histories. As the narrator walks along the Suffolk coast, the text meanders across centuries and continents and reveals hidden connections between capitalist extraction, imperialist violence, and ecological decline. Thus, it performs what Peter Sloterdijk has termed an explication: narratives latent in the landscape are brought into the foreground through the literary form (Horn 2020, 106).

The peculiar cartographic writings of Tim Robinson offer yet another instance of landscape aesthetics. In Connemara (2006), Robinson combines meticulous fieldwork with essayistic digression and sensory observation to write his literary maps of the western Irish islands. While walking the rugged landscape, he compiles “story maps,” a term used by Robert Macfarlane (2018), which integrate oral history, natural science, and personal experience. By situating the practice of mapping corporeally, Robinson challenges the abstraction of modern cartography, and, in this sense, his work is suggestive of earlier techniques of mapping, such as Aboriginal songlines or Italian portolan charts, where narrative and knowledge are more intimately linked. This ‘literary cartography’ can also be traced in other parts of Anglo-American literature from the latter half of the 20th century: from William Least Heat-Moon’s PrairyErth: A Deep Map (1991) and Barry Lopez’s Arctic Dreams (1986) to Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain (1977) and Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974), to name just a few illustrative examples. These works share a focus on regional landscapes and an innovative approach to nonfiction that employs literary techniques often associated with fiction and poetry, while insisting on empirical observation. In doing so, they offer a range of aesthetic models for writing about landscapes in the Anthropocene as a period marked by accelerating transformations in the relationship between humans and their environments.

Contemporary Art

Landscape in art has had a central and varied position when it comes to conveying meaning. This is not an exhaustive account of artistic engagement with the genre of landscape, but rather covers a few pertinent and salient themes that arise in recent contemporary artworks. Artistic practices address aforementioned shifts of relation to environment, such as the “apositionality” of landscape through new forms, methods and hybrid mediums of sensory representation which reflect entanglements in relation to the environment. These forms of representation include a recognition of the interactions between natural processes with technology, and situated sociopolitical and cultural histories that frame a relationship to the environment. These themes contribute to a plurality of ways in which we understand landscape, what it does and the ways we may relate to and within it.

As Media, or Letting Nature Speak

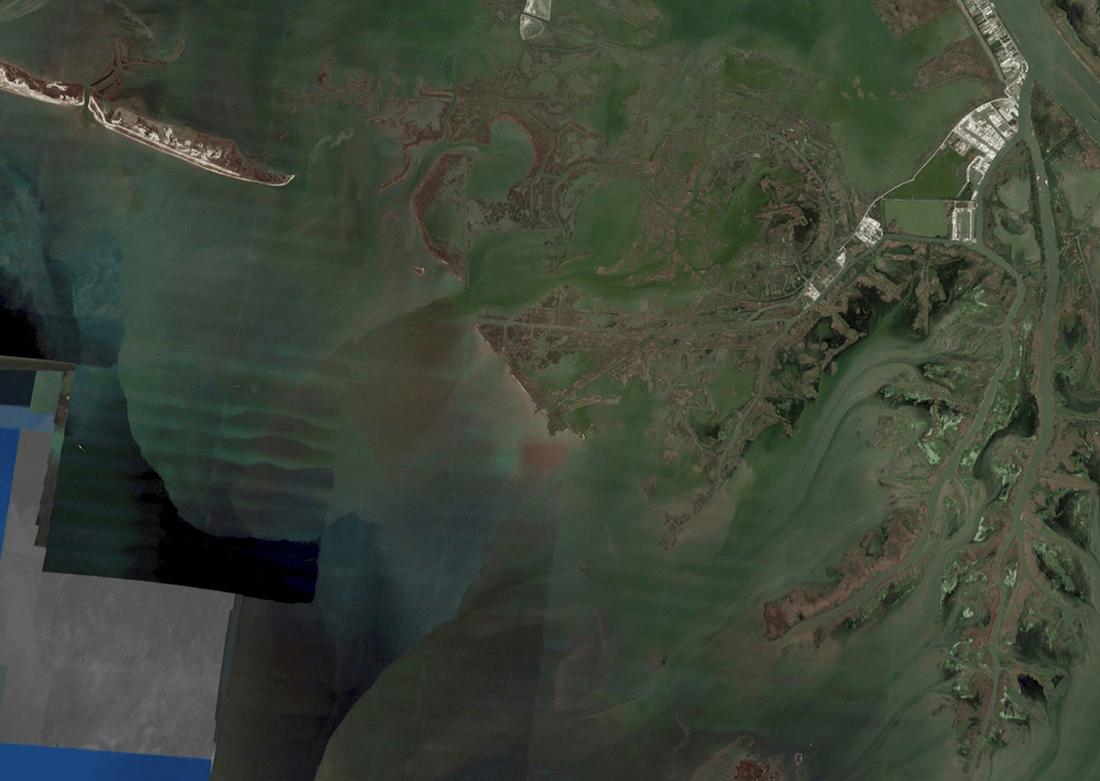

New forays of contemporary artists working in the genre of landscape reflect and engage with this changed positionality through the representational capacity of non-human agencies. One of the inroads towards this approach is an understanding of natural elements in the environment as media, that is that they have an inherent communicative capacity, whether or not commensurable with. Returning to Mitchell, he describes landscape as a medium that is, a means through which values and meaning are communicated, and which “mediates the cultural and the natural” (Mitchell 2002, 15). This attention to landscape as media, as a bridge between binaries of nature and culture, is further elaborated on and then crossed by John Durham Peters in his philosophy of elemental media, in which he references a 19th century understanding of media as nature, or rather the elements of nature that is, water, earth, fire and air (Peters 2015, 2). He describes a fundamental understanding of media as “the means by which meaning is communicated, [it] sit[s] atop layers of even more fundamental media that have meaning but do not speak” (Peters 2015, 2). Peters asks for an expanded understanding of media that crosses binaries of the “natural” and “cultural,” inevitably describing a contemporary condition of our technological environment. These perspectives frame what I consider to be a prevalent thread in contemporary artistic practice that involves artistic works which focus on letting nature speak, so to say, through mediated expressions of both elements and processes in nature. Through videoworks, artist and researcher Susan Schuppli, who discusses the term “material witness,” addresses how physical matter and processes in nature, such as oceanic waves, atmospheric circulation, or the composition of ice core samples, speak” to evidence of events in the contexts of war, climate change and environmental disaster (Schuppli 2020). Schuppli’s work engages with how environments can act as evidential records of human-induced crises, for example, the sensing of radioactive contamination in Canada’s coastal waters five years after the Fukushima nuclear accident and the traces found in water from the Deep Water Horizon drilling rig oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. In this approach, Schuppli’s own visual record through video and photographic documentation of the physical attributes of these materialities found in nature, “gives voice,” one could say, to the expressive and communicative aspect of environmental processes reacting to these events. This makes it possible for the utility of the documentation of these attributes to act as circumstantial evidence within the highly intensified register of jurisdiction. In her artistic video works, these events are made visible through a formal register, for example, through the patterns of oil that lie on the surface of the ocean, constituting images of abstraction. In its record, both audible and visual, Schuppli lets nature as media speak for itself. The events that have happened in and against nature are represented through form, offering their own expression, as Schuppli describes, as a witness to the events which have taken place. (Schuppli 2023)

Other artists, such as Nanna Debois Buhl and Amitai Romm, approach elements in nature as a medium in other contexts. For example, Buhl, in her series of works titled Helios (2024) and Lunar (2024), addresses how planetary forms such as the sun and the moon are translated into and through technical mediums. This includes weavings constructed from solar dyed thread and other intermedial works that visually translate the code of the first images of the far side of the moon transmitted to Earth, line by line, by a USSR space probe in 1959, into a woven medium. These woven works relate technical mediums with a history of craft and create images of cosmic landscapes not only in their formal representation but also through multiple layers of material expression. Other artists are working with sonic registers of natural elements and, in turn, create auditory and sensory landscapes. For example, Romm in his series titled Hum (2024) works with an environmental survey system in Sorø, Denmark that transmits data on carbon sequestration, that is, the process by which carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere and stored in solid or liquid form, from a beech forest there and recodes this data into sound waves sensed through a viewer’s body. These artists are representative of contemporary artistic practices that draw on an approach towards nature and environment as a medium that encompasses processes of mediation, experimenting with how these can “speak” and, in turn, construct aesthetic forms. This focus on the mediated aspects of environmental processes and elements in nature in artistic practice connects to foreground and expand the recognition of wider ecologies of non-human intelligence.

Artists are increasingly experimenting with the aesthetics of technical platforms, especially in the ways visualisations of environment are generated on planetary scales and the treatment of land as a source of data, producing landscape visualisations, shaped by and known through analyses of data. Artists such as Daniel Lefcourt, Mishka Henner, Quayola, and Emmanuel Van der Auwera, in different ways, address the visibility of multiscalar layers of data, logics and material infrastructures (Lee-Morrison 2023). Their artworks address the ways data production can shape landscape through both visualisations as well as its physical actuality, through mining and practices of extractivism for minerals used in the development of digital technologies. Van der Auwera’s video work titled “VideoSculpture XXX (The Gospel)” (2024) includes AI-generated images of the Bayan Obo mines in Mongolia that are known for being the largest site of rare earth mineral deposits, which are mined to produce smartphones, digital cameras and flat screens. There are multiple levels of representation in this work that merge data and the physical materiality of landscape framed through logics of extraction. The work addresses two forms of mining that are interrelated: firstly, that of images on the internet to produce aggregated AI-generated images of this landscape, and secondly, the mining of minerals that shapes the physical landscape itself to produce the material resources that, in part, constitute the medium of the screen upon which AI images are displayed. It addresses how modern technologies are bound with environmental processes, foregrounding the materiality of the digital while at the same time addressing the challenge of representing these relations as ephemeral and difficult to trace. The mining of these minerals causes mass pollution in the surrounding environment in the form of acidic wastewater, radioactive sludge and contaminated soil (Bicker 2025). Images and visibility of the area are highly restricted, with the Chinese government sensitive to criticism. Against the hypervisibility that is achieved through contemporary digital technologies, Van der Auwera’s work traces the invisibility.

Coloniality

The approach towards landscape as a backdrop to human action and events is, in part, described by visual culture scholar Nicholas Mirzeoff as a central power relation. In his study of decolonising the gaze, he traces histories of both colonial expansion and military prowess through the figure of the “overseer” (Mirzeoff 2011, 35). This refers to an institutional dominance gained through a visual perspective, which occurs through a situated perspective that can see over the entirety of environments, for example, colonised land and its resources, or the environments of battlefields. Mirzeoff argues that it is through this perspective that both colonial dominance and military advantage have transpired (Mirzeoff 2011, 35). This perspective is directly countered by contemporary artists in approaches towards visualising the environment through alternative framings, such as the lens of indigenous knowledge and haptic forms of seeing the landscape. These approaches also include regional focuses on areas considered to lie at the periphery of metropoles. The work of artists such as Pia Arke, Imani Jacqueline Brown, Liu Chuang and Sarker Protick can be considered within this context, providing new perspectives on landscape through subjective relationships to land and in countering views of landscape as ahistorical. Arke, whose photographs of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland) merge the image genres of self-portraiture and landscape, foregrounding a subjective relationship with and to environments within a historical context of Danish colonisation and its institutional processes of subjectification. Brown, in her work titled The Remote Sensation of Disintegration (2020), appropriates the aerial gaze from a military and institutional context and instead frames it through the lens of a haptic gaze (Lee-Morrison 2025). In this, her work presents a view of the region occupied by the fossil fuel corporations in New Orleans called Cancer Alley through an embodied sense perception and contextualised within histories of African slavery that have characterised the landscape. In the work titled “Lithium Lake and Island of Polyphony,” the video artist Chuang traces a historical relationship between the transfer routes of mined precious metals from silver to lithium. As part of the work, aerial views of the world’s largest salt lake, the Uyuni Salt Flat, located in Bolivia, are displayed. Here, the transformative process of salt turning into lithium ore is visualised as connecting remote parts of the world through mineral trade and producing a planetary-scale landscape image, constituted by sites of extraction and distribution. Protick, in his photographic series titled Awngar (2024), documents histories of British colonisation of the Indian subcontinent and its apparatus of environmental survey for both mining and the establishment of a train network. His images aestheticise the traces that these operations of colonial domination and extraction leave in the landscape of Bengal and present-day India.

Conclusion

In sum, this entry has traced the evolving notion of landscape from a neutral backdrop to human activity toward a dynamic, agentic medium, both shaped by and shaping human and nonhuman relations. Across contemporary literature and art, we have seen how conventional aesthetic modes of representation, rooted in perspectival frameworks, have been challenged by artistic practices that reconfigure positionality, scale, and the relationship between human and nonhuman perception. In literature, representations of landscape respond to the demands of the current era by inventing forms that unsettle the boundary between subject and environment. Likewise, contemporary artistic practices are developing new modes of sensing and witnessing that document landscape as a communicative medium, whether through planetary-scale data or haptic visualisations that resist the colonising gaze. Taken together, these examples illustrate how landscape today is imagined as a site of aesthetic, political, and ecological negotiation.

As ecological crises deepen on a planetary scale, the need for representational forms capable of registering the complex temporal and spatial scales of human and nonhuman histories becomes ever more urgent. Reconfiguring landscape as a site of relation rather than human mastery offers not just a critique of inherited visual and literary conventions, but a way of imagining more reciprocal modes of inhabiting our shared environment. In this sense, landscape aesthetics remain crucial to reorienting ourselves both ethically and imaginatively, in response to epistemic shifts in relation to the environment.

References

Alexievich, Svetlana. 2016. Chernobyl Prayer: A Chronicle of the Future. London: Penguin Modern Classics.

Bicker, Laura. 2025. “Poisoned water and scarred hills: The price of the rare earth metals the world buys from China.” BBC News, July 8, 2025. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-66cdf862-5e96-4e6e-90b8-a407b597c8d9.

Brown, Imani Jacqueline. 2020. “Remote Sensation of Disintegration,” videowork, 6 min. https://imanijacquelinebrown.net/The-Remote-Sensation-of-Disintegration.

Cosgrove, Denis E. 1998. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

DeLue, Rachael Z. 2007. “Elusive landscapes and shifting grounds.” In Landscape theory, edited by Rachel DeLue and James Elkins, 3-14. Milton Park: Routledge.

Dillard, Annie. 1974. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. New York: Harper’s Magazine Press.

Foster, Tristan. 2024. “‘The Past Survives In The Telling’: Eight Questions For Esther Kinsky.” publicbooks.org. https://www.publicbooks.org/the-past-survives-in-the-telling-eight-questions-for-esther-kinsky/.

Ghosh, Amitav. 2016. The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Heat-Moon, William-Least. 1991. PrairyErth: A Deep Map. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Horn, Eva, and Hannes Bergthaller. 2019. The Anthropocene: Key Issues for the Humanities. Milton Park: Routledge.

Ingold, Tim, 2021. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. Milton Park: Routledge.

Jay, Martin. 1988. “Scopic Regimes of Modernity.” In Vision and Visuality: Discussions in Contemporary Culture, edited by Hal Foster, 3-23. Seattle: Bay Press.

Kinsky, Esther. 2022. Rombo. London: Fitzcarraldo Editions.

Latour, Bruno. 2016. “Let’s touch base.” In Reset Modernity!, edited by Bruno Latour, 11-23. Cambridge, MA and London: The MIT Press.

Latour, Bruno. 2017. Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Lee-Morrison, Lila. 2023. “Machinic Landscapes: Aesthetics of the non-human.” Media+Environment 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.1525/001c.88423.

Lee-Morrison, Lila. 2025. “The Environmental Gaze: Visual perspectives on monitoring landscapes of ecological devastation,” In Media Matters in Landscape Architecture, edited by Karen M’Closkey and Keith VanDerSys, 208-219. Novato: ORO Press.

Lopez, Barry. 1986. Arctic Dreams: Imagination and Desire in a Northern Landscape. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Macfarlane, Robert. 2018. “Wizards, Moomins and pirates: the magic and mystery of literary maps.” The Guardian, September 22, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/sep/22/wizards-moomins-and-gold-the-magic-and-mysteries-of-maps.

Metz, Christian, 1982. The imaginary signifier: Psychoanalysis and the cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Mirzeoff, Nicholas. 2011. The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mitchell, W.J.T. (ed.). 2002. Landscape and Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Morton, Timothy, 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Olwig, Kenneth. 1996. “Recovering the Substantive Nature of Landscape.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 86 (4): 630-53.

Peters, John Durham. 2015. The Marvellous Clouds: Towards a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Robinson, Tim. 2006. Connemara: Listening to the Wind. Dublin: Penguin Ireland.

Schuppli, Susan, 2020. Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schuppli, Susan. 2023. “Denaturalizing the Image: An Interview with Susan Schuppli.” Interview by Lila Lee-Morrison. Media+Environment 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.1525/001c.87976.

Sebald, W.G. 1998. The Rings of Saturn. London: New Directions Books.

Shepherd, Nan. 1977. The Living Mountain. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, Jennifer Deger, Alder Keleman Saxena, and Feifei Zhou. 2024. Field Guide to the Patchy Anthropocene: The New Nature. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.