Heterarchy

Bruno De Meulder and Kelly Shannon

Related terms: anarchism, horizontal city, secondarity, self-organisation, stateless societies, vernacular landscapes

‘Heterarchy’ is most simply defined as an organisation of things – people, groups, ideas – where no single part dominates. It is an organisation where nothing and nobody is in charge or ranked above others. In a heterarchy, the relationships and rankings can change depending on the situation and different parts can lead or follow as needed. Throughout the world, modern history has been over-determined by hierarchical and centralised approaches, which are becoming ever more reinforced through politics, neo-liberal economics and advances in technology, particularly with what historian Yuval Noah Harari would call an “alien intelligence” of unfathomable algorithms (Harari 2024). In the environmental humanities, the reactivation of the concept of ‘heterarchy’ can offer a foil to the biases in the era of the Anthropocene and fundamentally recalibrate nature-culture and environment-humankind relationships. It offers an alternative conceptualisation of how humanity understands, represents, and interacts with the world. In the cascade of contemporary crises – particularly driven by the myriad consequences of global warming (massive biodiversity loss, threats to human health, increase in ‘natural’ disasters and climate refugees), and increasing socioecological injustices – thinking and acting in terms of ‘heterarchy’ seems to indicate a pathway forward.

Etymologically, ‘heterarchy’ consists of the Greek words heteros, meaning ‘the other,’ and archein, meaning ‘to rule.’ It is a fundamental organization principle of complex systems and mediates the dialectic between hierarchy and anarchy. Opposed to the predictability of pyramid-like organisation, heterarchy operates as a web or network, where relations and influence change depending on the context and the concrete situation at hand. ‘Heterarchy’ describes a structure where relationships are not fixed in a single order, but can change, overlap, and adapt, with authority or importance shifting based on the situation or perspective. In this way, it has similarities to “string figures” and their associated metaphors as developed by Donna Haraway (Haraway 2016). It is commonly defined as “an order and set of values that are explicitly local, consensual, without leaders/followers and not hierarchical” (Crumley 2005, 48). The notion of ‘heterarchy’ was first used in neuroscience (in 1945 by Warren McCulloch) in relation to the way the human brain defies both singular, linear ranking and predictability, and it was linked to complexity theory. McCulloch’s paper “A Heterarchy of Values Determined by the Topology of Nervous Nets” described systems that lacked a single, dominant value or endpoint. The concept of ‘heterarchy’ was later conceptually employed in numerous disciplines, particularly from the 1990s onwards, including archaeology, anthropology, the biological sciences, sociology, and politics. In archaeology, Carole Crumley stated that heterarchy is considered both “a structure and a condition” (Crumley 1995, 4) and is a non-linear, flexible and dynamic form of organisation. It is “related to the juxtaposition of cognitive and ecological liminality with flexible power relations” (Crumley 1995, 3). Heterarchies inherently resist static equilibrium, refute dualities, and do not act predictably; they are often linked to the notions of fluidity, emergence, and self-organisation. Again, quoting Crumley, “heterarchical relationships are implicated in the dynamic effect of difference, be it spatial, temporal, or cognitive” (Crumley 2005, 40).

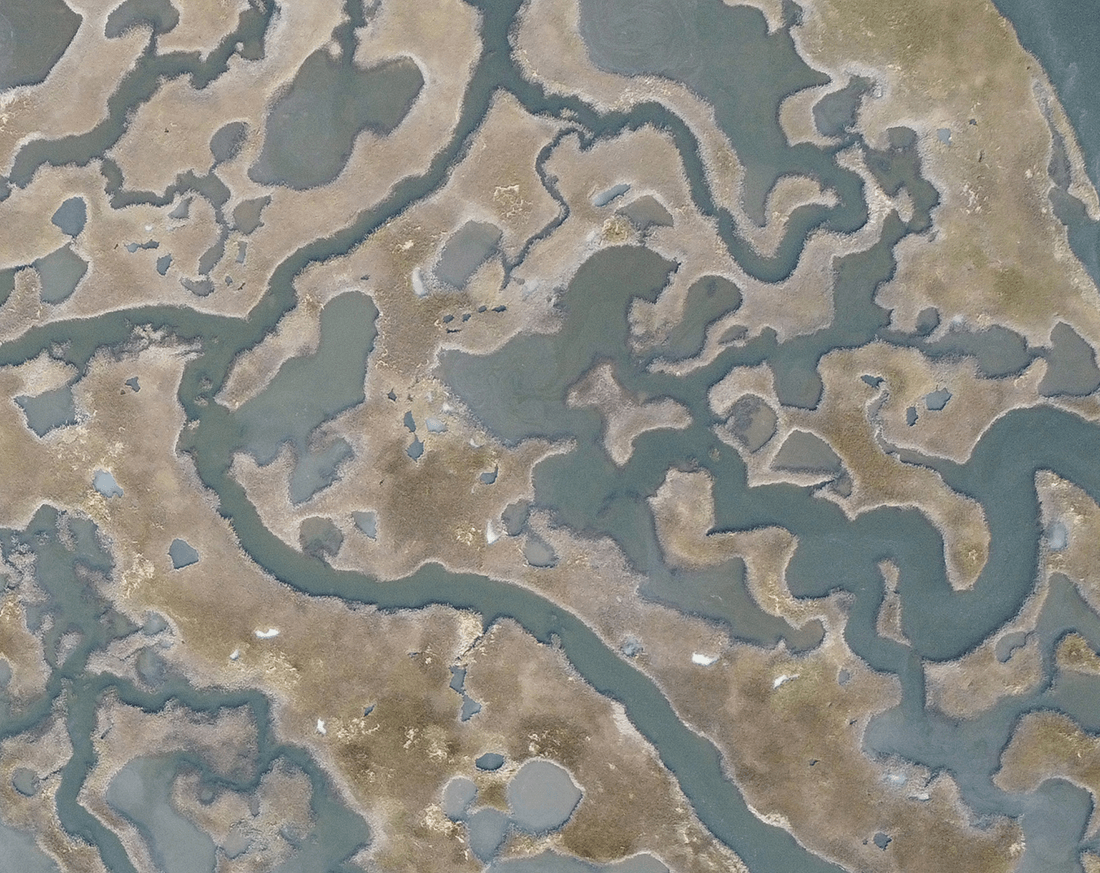

In the physical environment, particularly ecology and urbanism, ‘heterarchy’ is linked to different spatial scales and related to adaptability and interactivity. Alexander von Humboldt’s late 18th century concept of the web of life revolutionized how nature is understood in Western thought, emphasized interconnectedness and interdependence among human and non-human life of/on the Earth – an understanding that has always been self-evident in non-Western (and non-mechanic) worldviews that resonate amongst others in Buddhism, Taoism and emblematically in the embracing of the Mother Earth figure by Indigenous cultures in Latin America. Von Humboldt envisioned nature as a dynamic, intricate tapestry, where every element is interwoven to form a global system of interactions (von Humboldt 1850). Although his work predated the dubbing of ‘heterarchy,’ it laid the foundation for modern ecological thought and environmental science, where ‘heterarchy’ plays a part. It is worthwhile acknowledging that von Humboldt’s concept of interconnectedness of nature (a heterarchical nature) was largely shaped by his observations of Indigenous knowledge systems and the exchanges with Indigenous communities (Eibach & Haller, 2021). Similarly to von Humboldt, the work of Elinor Ostrom’s well-known research on common-pool resources and collaborative governance (Ostrom 1990) aligns with notions of ‘heterarchy,’ without her explicit use of the term. Conversely, the term itself has gained significant traction in the emerging field of historical ecology, which traces complex adaptive relationships over the longue durée.

As a notion mediating between the dialectic between hierarchy and anarchy, ‘heterarchy’ is an open invitation to transcend dichotomies that have been dominant in Western thinking.

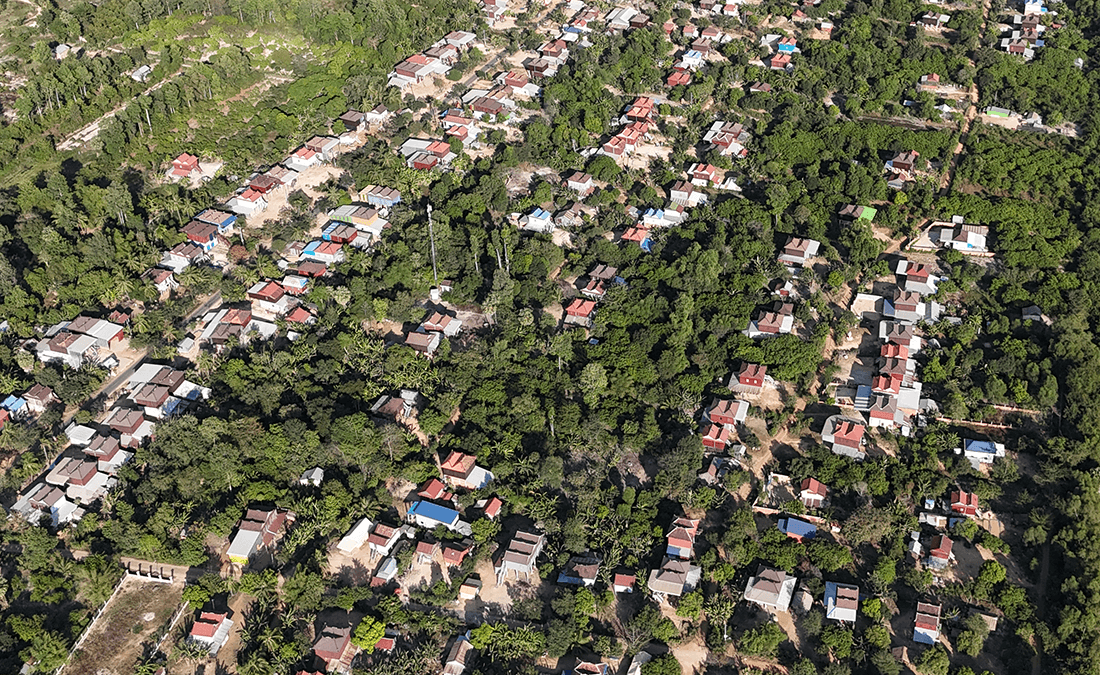

In relation to urbanism, ‘heterarchy’ resonates ‘secondarity’ that the Belgian urban sociologist Jean Remy paired with primacy, breaking open the conventional centre-periphery dichotomy that long dominated thinking in urban studies, urban planning and urbanism (Remy & Voyé 1981, Remy 1998). ‘Secondarity’, or ‘interstitiality,’ is all about the shadow of the centre, escaping strict order and instead adapting, where things are flexible and relatively freer. Secondary spaces are more innovative and allow more experimentation than central ones. Most importantly, interstitial (or secondary) spaces were real physical spaces for Remy. One of his primary interests was the relation between urban spaces and social interactions (which he defined as social transactions). Space for Remy was not a background, but, in line with, while different from Henri Lefebvre (Lefebvre 1991), a socially constructed foreground, ingrained with meaning through collective practices. ‘Secondary spaces’ remind us of what Claude Lévi-Strauss labelled “floating signifiers,” signifiers that are somehow apt to receive any meaning (Lévi-Strauss 1988, 63-4). In other words, they could be understood as the spatial match with systems that lack a single, dominant value or endpoint. Spatially, ‘interstitial spaces,’ as described by Rémy, were mostly old environments that missed the boat of reinvestment – those places out of sight, out of the light, and informally recycled by those in the shadow of society, far away from where new central developments took place (Remy 1998).

John Brinckerhoff Jackson’s conceptualisation of ‘vernacular’ landscapes mirrors Remy’s notion of ‘secondarity.’ For Jackson, an American chronicler of the environment, vernacular landscapes were identified with local custom, pragmatic adaptation to circumstances, a slow and subtle evolution, and an inexhaustible ingenuity in finding short-term solutions. For him, they are a foil to “political landscapes,” established and maintained and governed by law and political institutions, dedicated to permanence and planned evolution (Jackson 1984). Like heterarchy and hierarchy, vernacular and political landscapes coexist. James C. Scott explained in his canonical Seeing Like a State, with case studies on notorious spatial planning exercises such as the Ujamaa villages in postcolonial Tanzania, that there have been disastrous (almost always failed) attempts to radically impose political landscapes by eradicating the vernacular (Scott 1998).

Keeping in mind Rémy’s unravelling of relationships between space and social transactions, foundational texts like Christopher Alexander’s A City is Not a Tree relate to heterarchy. Alexander criticised ‘tree-like’ hierarchies that dominated urban planning models of the ‘high modernist’ (in the words of Scott), rigid and top-down structures, where each part “solely interacts through predefined relationships with higher up elements” (Alexander 1965, 10). He puts forward the concept of a ‘semi-lattice’ as a structure “where elements overlap and interact in multiple ways, and capable of accommodating a wide variety of unpredictable and ever-changing practices” (Alexander 1965, 12). Alexander moved from theory to practice with his book A Pattern Language that unfolded a practical framework for designers to build cities as ‘complex living systems’ by applying patterns that allow for ‘fluid’ (or perhaps ‘floating’ to remain in Lévi-Strauss’ terminology) connections across scales, fostering adaptability and inclusivity (Alexander 1977). Patterns are understood as interdependent and non-linear “elements that interact with larger scale elements in multiple ways” (Alexander 1977, 45). In other words, a semi-lattice structure allows for heterarchical relationships, supporting a variety of human needs and fostering resilience. ‘Heterarchy’ is about flexibility, fluidity, adaptability, and resistance.

In urbanism or, more broadly, settlement, such a non-functionalistic and non-deterministic yet ‘floating’ link between urban space and social transactions makes one understand that ‘heterarchy’ invariably forces a focus on context specificity, particularly regarding (secondary) space and time. If, as Alexander claimed, “the reality of today’s social structure is thick with overlap,” a “thick, layered physical space with a long history, capturing a multitude of practices, might be more capable of acting as a ‘floating signifier’” (Alexander 1965, 10).

Other attempts to move urbanism away from conventional obsessions with hierarchy and centrality appeared in publications like A World of Variation by Mary Otis Stevens and Thomas McNulty (Stevens and McNulty 1970). They expounded conceptually decentralising hierarchies and a radical re-envisioning of social and spatial relationships. Their rich collections of images included many examples from biology and close-ups of objects and species in the non-human world, a world of variation. Fifty years later, the urbanist Paolo Viganò advanced the notion of ‘isotropy’ through her definition of the ‘horizontal metropolis’ (Cavalieri and Viganò 2018). The concept of the ‘horizontal metropolis’ matches seamlessly with the spread-out form of contemporary cities worldwide as well as with the horizontal relationships between agencies within such an urban reality. However, the notion of ‘isotropy’ is at odds with the rich variety that characterises contemporary urban environments. The term loses the complexity and specificity within environments. Conversely, taking note and advantage of the specificities of (magical) spaces was a conscious purpose of the label ‘lieux magique’ (magical place) that the then French president, François Mitterand, developed in the Banlieues ’89 program. The program sought to recognise the heterogeneous qualities within the French banlieues (peripheral housing estates), stereotyped as monotonous and overloaded with social stigma. For Banlieues ’89, every square kilometre contained at least one ‘lieu magique’ to capitalise on, to exploit its locational assets (Ledeboer 1993) and celebrate its uniqueness.

There is no better model than the ‘rhizome’ when locational assets and specificities are on the agenda. The concept was put forward by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari to contrast conventional hierarchical models (Deleuze and Guattari 1980). ‘Rhizomes’ (in botany, the underground root system of mushrooms) are defined as dynamic elements, growing opportunistically and exploiting any locational asset in terms of nutrition (and fluid). A rhizome does not have a centre but embeds itself seamlessly in an ecosystem. As never-ending (or never-beginning) systems, rhizomes are capable of regenerating and re-growing themselves.

Spatially, the rhizome contrasts with the tabula rasa furies of modern times, which have by now, paradoxically, led to a tabula plenum – a world full of structures, constructions, remnants, and traces (Roberts 2016). Unfortunately, this has also led to an array of broken ecologies, wasted lands by extraction, felled forests, and melted glaciers. There is no place without traces of construction or destruction. Humankind is everywhere, builds everywhere, and pollutes everywhere. Rachel Carson remarked already in the 1960s that, while all living species have an impact on their environment, man was without doubt the “most untidy of all species” (Carson 1963). There is no pristine or virgin ‘new world’ to conquer and occupy. In the early 1980s, André Corboz described land as a ‘palimpsest’ (Corboz 1983) and suggested that traces in the territory should be the start for any sensible project. Urbanism, surely in the postindustrial world, is no longer about the new or the extension, but rather about the deepening of the territory, a continuous labour of re-editing, of rearticulation of the landscape that already is full of signs (not necessarily ordered or forming coherent sets) (Marot 2010). In this move towards a cyclic urbanism of some kind, it is evident that locational assets can be re-emphasised and a multitude of agencies can engage with opportunities here and there and a bit everywhere in order to anchor the new on existing artefacts, to reuse and repurpose structures. The continuous transformation of urban territories is by definition heterarchical. There is no central command. Since the advent of the car and, more recently, the development of new technologies that further distribute and decentralise systems, the notion of centrality has fundamentally eroded, as Saskia Sassen (amongst others) has remarked (Sassen 2015). The urban is now everywhere, and it is heterarchical.

Returning to the groundbreaking works of the built environment where the notion of ‘heterarchy’ was developed, French anthropologist Pierre Clastres’ study of pre-Colombian Amazonian communities (the Guayaki, Yanomami, Tupi and Guarani) demonstrated that they were not ‘primitive’ precursors to statehood, but sophisticated systems using heterarchical principles to prioritise autonomy and egalitarianism. The chief, as far as there is one, does not have coercive power as in states. Society itself, and not the chief, is the real locus of power (Clastres 1974). Other anthropologists have since continued the line of inquiry begun by Clastres. William Balée has written extensively about heterarchy in his work on ecological transformation by forest-based Amazonian societies (the Ka’apor, Tembé, Assurini and Araweté), which were, according to him, connected by kinship and decentralised daily practices (Balée 1994; Balée 1998).

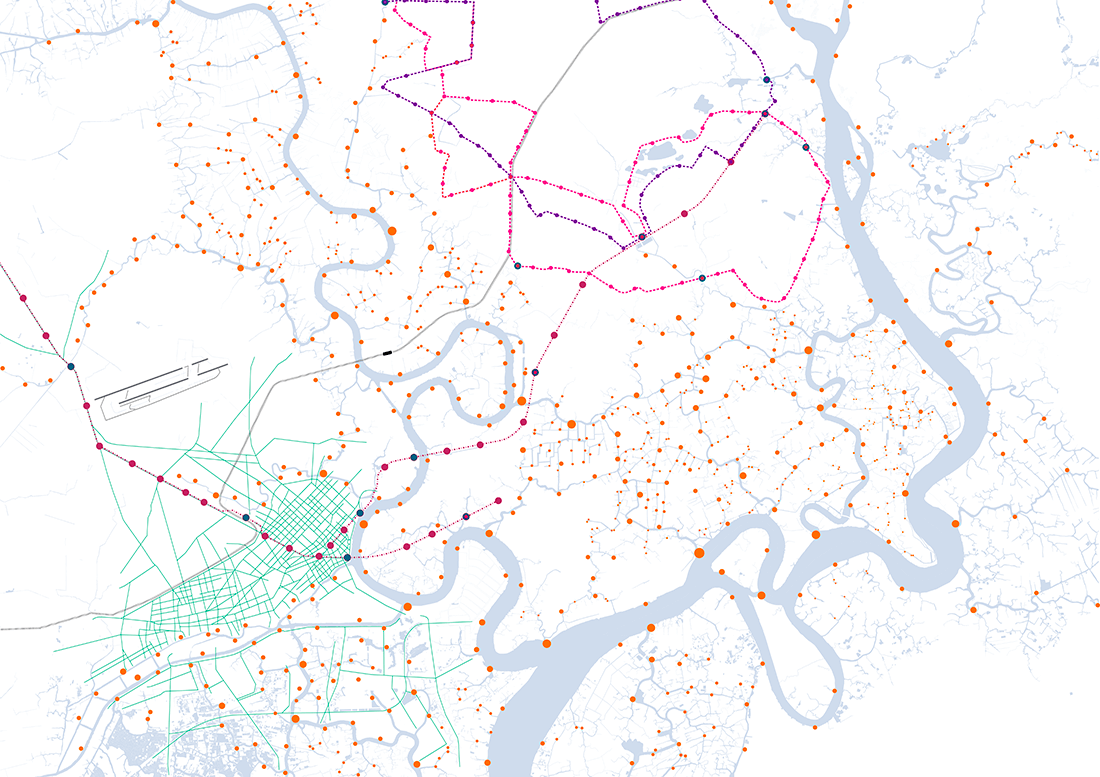

The work of anthropologists in Amazonia was mirrored in research on pre-colonial contexts where collaboration, distributed power, inclusivity, and knowledge from various groups contributed to spatial formations and their adaptation. Roderick McIntosh’s work in the dispersed clustered city landscape (Dia and Jenne-Jeno, in present day Mali) of the Ancient Middle Niger reveals that “heterarchies are preeminently those complex systems that can evolve out of simpler forms because their constituent agents share a few simple rules about how to learn from and provide information to their neighbors.” In heterarchies, McIntosh explains, “individuals are acutely attuned to the states of surrounding elements and surrounding environmental inputs (bio-physical and social), rather than passively awaiting directions from the pacemaker” (McIntosh 2005, 43). For him, such a heterarchical logic of highly complex societies is organised horizontally, drawing upon multiple overlapping and competing agencies of sustained resistance to centralisation. The self-organised societies and their landscapes and settlement systems had neither kings nor a state (McIntosh 2005, 187-89). McIntosh ends his work with a critical comparative analysis, referencing scholarship of alternative cityscapes of Mesopotamia (Mashkan-shapir) and the Upper Nile (This, Naqada and Hierakonpolis), as well as the work of Kwang‐chih Chang on Shang Dynasty northern Chinese cities (Anyand and Zhengzhou) where there was a persistent nesting of clustered specialist locales.

In Western Europe, the emergence of cities in the Middle Ages was linked to an interrelation of kingdoms, monasteries, universities, military outposts, or civic strongholds. Settlements had a multiplicity of irregular and spontaneous forms and responded to specific geographical conditions. The ring wall, built as a military defence system, merely encircled and contained urban development; it did not order it. Medieval cities in Western Europe were organically filled with houses, convents, ‘beguinages’ (in the Low Countries), churches, taverns, inns, alehouses, workshops, metalsmiths, breweries, bakeries, and sometimes shipyards. Medieval cities have been described as heterarchical due to the multi-functionality of spaces and the forever evolving alliances and interactions of hierarchical institutions (Crumley 1979; Boone and Howell 2013; Bania-Dobyns 2008). Cities obtained their autonomy (rights of self-governance) from kings or other nobles (implying rights for their citizens/ burgers/ bourgeois) and functioned in non-hierarchical networks (with the Hanseatic League being one of the most emblematic examples) (Schulte Beerbühl 2012). Many medieval cities – as spaces of living apart together (stretching Roland Barthes’ ‘living together’) (Barthes 1977) – were as much ordered by convents, monasteries and churches/parishes as by markets/ market halls, guild houses and early banks, or by proud city authorities and palaces of the nobility. The medieval city in Western Europe can be read as a constellation of markets (fish markets, egg markets, grain markets, butter markets, horse markets, etc.) and halls (for general purposes and as well specialised, such as the cloth halls); they can alternatively be understood as a system of churches or convents. ‘Spontaneously’ or organically growing around monasteries and strongholds, medieval cities in Western Europe were both institutional and spatial patchworks, with churches, city authorities, and merchant guilds competing and cooperating, structured as archetypal heterarchies (Piron 2008). It is not surprising that ‘heterarchy’ has become a key concept during the last decades for medievalists also.

As the Middle Ages faded and embryonic nation-states emerged, modern town planning established pretences of order, rationality, and foresight. Cities have become more complex, accumulating, containing and hosting ever more elements. In the meantime, it has become commonplace to mention the multiplicity of the city and to highlight the systemic value contained within its constellations of elements. Perhaps most striking in the many analyses of multiplicity is the emphasis on efficiency and flexibility. Nothing in the city is fixed forever; everything is in eternal flux. Early town planning treatises, such as that from the Flemish humanist Simon Stevin (mathematician, engineer, and physicist), could as well have been read as mathematical treatises (Van den Heuvel 2005). Mathematics for Stevin was ‘wis-kunde’ (wis: certain – kunde: knowledge): the knowledge of what is certain. Stevens’ town plans order a limited number of categorised elements in an orthogonal grid. There is no place for difference, doubt, surprise, or misalignment in this mathematical world. There is only one place for predictability and logical formulas, regularity and efficiency. The beauty of geometry, allegedly. A merchant’s house has specified dimensions and adjacencies. Grids bring order into the chaotic world of nature. The use of geometry, measuring, and assigning dimensions was assumed to be a way to master disorder, to discipline the unruliness of the world. Nature was replaced by culture (civilisation). Ever since the Renaissance town planning of Simon Stevin and all those of his time and in the generations that followed, whether labelled ‘stedebouw’, town planning, ‘urbanisme’, ‘urbanistica’ or ‘städtebau’, there has been an obsession concerning order, regularity, and predictability. Methods were determined (and supposedly perfected) to assign fixed, ‘rationally determined’ places to things, people, functions, all with regularity and ‘measure.’ Would it be possible to maintain a State without regular tax systems? Would commerce flourish when products were not calibrated? Are not the needs of the universal human, whose (male) measures were captured in the Modulor of Le Corbusier, the alpha and omega of modernist planning?

The development (and the current implosion) of urbanism and urban planning are remarkably intertwined with the advent of the nation-state and the gradual construction of its apparatuses. During the high days of modernist urban planning after the Second World War (with many nations still in a war state of mind and with an intact commando style of power that resonated the Cold War climate), archival material shows the urban planner alongside the prime minister, the technician and politician as the duo-center of an enormous state machinery, organizing and integrating society and space, typically in a fixed, orderly, hierarchical system. Risk and unpredictability were minimised as everything was prescribed through a reductionist and functionalist approach that was programmed in 5- or 10-year plans. For a long time, (modernist) urbanism and planning were compulsively seen as a public or State responsibility. The socio-economic perspective of urban planning was infected with ideas of hierarchy and centrality (reflected in evermore strict zoning and land-use legal instruments). Walter Christaller’s central place theory has been (and remains until today) a key reference in regional and urban planning (Christaller 1933). The high days of (modern) urban planning in the West are long gone, along with the illusion of its power. More than a decade ago, Neil Brenner, Peter Marcuse, and Margit Mayer lamented the marginalisation of public-interest planning in the era of neoliberalism (Brenner et al. 2011). Vanessa Watson shares this view (Watson 2009), without distinguishing between North and South contexts, while emphasising the loss of the agency of planners, as they have become only one among the many actors in contemporary urban governance systems. In other parts of the world, nation states with highly centralised systems are struggling to keep up the appearances of efficiency, adequacy and legitimacy of power.

Despite the dominance of mono-use zoning to create homogenised developments globally, there have been (and continue to be) ideas and projects that focus on heterogeneity. In the mid-1980s, there was the notion of ‘urban assemblage’ introduced by Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter in Collage City. They suggested that the city should be conceived as a collage which is assembled from diverse set of entities from past, present and future, an aggregate of discontinuous fragments re-situated in new contexts “objects and episodes are obtrusively imported and, while they retain the overtones of their source and origin, they gain also a wholly new impact from their changed context” (Rowe and Koetter 1984, 140). A decade later, Bernard Tschumi took the notion of assemblage one step further with the concept of ‘event montages,’ where the relationship between space and its use was to be understood sequentially. Such a sequence was a heterogeneous “composite succession of frames that confronts spaces, movements and events, each with its own combinatory structure and inherent set of rules” (Tschumi 1994, 10). Around the same time, social scientist Manuel Castells wrote extensively of the ‘network society’ where decentralised relationships and structures overlap across levels, creating dynamic, flexible, and adaptable societies. For him, both the ‘space of flows’ (new forms of networks) and ‘space of places’ (local and historically rooted spaces) align with principles of heterarchy (Castells 1996). Castells, however, also observed new forms of centralisation within decentralised networks. Indeed, heterarchical and hierarchical systems are both omnipresent. After a century and a half of emphasis in urbanism on hierarchy and centrality, it seems timely to recognise heterarchy as an inevitable reality on which contemporary urbanism should anchor itself, while trying harder to understand it. In its iterations, worthwhile urbanism oscillates between understanding the urban condition and intervening in it based on such an understanding. Heterarchical systems should be recognised as key stakes in these iterations, besides the eroding hierarchies that still somehow stay upright.

The reactivation and foregrounding of ‘heterarchy’ as a conceptual frame to re-read and re-formulate nature and culture relations is fundamental in contemporary environmental humanities. ‘Heterarchy’ is a subversive and transformative lens from which to address the limitations of hierarchical and binary models. Nature and culture are co-constitutive (not oppositional) and deeply entangled. Heterarchical structures accommodate dynamic, lateral connections (often alongside hierarchies) and are necessary to tackle socio-ecological challenges. ‘Heterarchy’ also embraces a multitude of knowledge systems, including scientific ecological knowledge (SEK), traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and Indigenous knowledge systems and practices (IKSP). The concept is an essential element in the critique of extractive and exploitative colonial legacies. Heterarchical systems can (re) centre the marginalised (both human and non-human species) and be integral to advancing socio-ecological justice. In this quest for socio-ecological justice, the potential of heterarchical systems ally themselves with the pluriverse as advocated by anthropologists like Arturo Escobar, who base their insights on decades of work with Indigenous and marginalised groups (Escobar 2008; Escobar 2020). Neither in heterarchy nor in the pluriverse is reality reduced to a simple perspective, nor is an organisational hierarchy implied. As in heterarchies, the pluriverse understands reality as constituted by a multiplicity of relationships and structures. The concepts of ‘heterarchy’ and ‘pluriverse’ both seek to make space for difference, plurality, and the possibility of alternative forms of organisation (in the case of the pluriverse, often inspired by Indigenous worldviews and their traditional ecological knowledge).

In spatial terms, heterarchies are important as foils to the reductionist paradigms of modernism, land-use zoning, and quantitative-based urban planning. They are invariably more messy and more complex systems, but clearly ones that lend themselves to a dramatic reconceptualisation of humankind’s occupation on the earth – reweaving the most prevalent land coverage of forestry, agriculture, and settlement – into new hybrids that simultaneously heal disturbed ecologies and initiate new relationships with non-human species. The ‘pluriverse’ and ‘heterarchy’ are not only theoretical concepts of description but also keys for the (iterative) construction of ‘other possible worlds’ (Escobar 2018). In this respect, the hints of Escobar for a renewed alliance between design and anthropology are refreshing after decades of humankind’s deaf conversations between disciplines. For Escobar, ‘design/ing,’ as acting-knowing, is emerging as a fundamental domain for thinking about life itself and the making of worlds. Escobar defines ‘design’ as “a praxis for the healing of the web of life, an important praxis against what some Indigenous women activists in South America call terracide” (Escobar 2021, 171).

References

Alexander, Christopher. 1966. “A City Is Not a Tree.” Design 206: 1–17. London: Council of Industrial Design.

Alexander, Christopher, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein. 1977. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Balée, William, ed. 1998. Advances in Historical Ecology. New York: Columbia University Press.

Balée, William. 1994. Footprints of the Forest: Ka’apor Ethnobotany—The Historical Ecology of Plant Utilization by an Amazonian People. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bani-Dobyns, Sarah. 2008. “Hierarchy or Heterarchy? Actors of Medieval International Society at the Council of Constance and the Peace of Augsburg.” International Studies: Faculty Scholarship.

Barthes, Roland. 1977 (2013). How to Live Together: Novelistic Simulations of Some Everyday Spaces. Translated by Kate Briggs. New York: Columbia University Press.

Boone, Marc, and Martha Howell. 2013. The Power of Space in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers.

Brenner, Neil, Peter Marcuse, and Margit Mayer, eds. 2011. Cities for People, Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City. London: Routledge.

Carson, Rachel. 1963. “The Pollution of Our Environment.” Reprinted in Woods, The Discovered Writings by Rachel Carson, edited by Linda Lear, 227–45. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998.

Castells, Manuel. 1996. The Rise of Network Society. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Cavalieri, Chiara, and Paola Viganò, eds. 2018. HM: The Horizontal Metropolis, a Radical Project. Zurich: Park Books.

Clastres, Pierre. 1974 (1987). Society Against the State: Essays in Political Anthropology. Translated by Robert Hurley and Abe Stein. Cambridge, MA: Zone Books.

Christaller, Walter. 1933. Die zentralen Orte in Süddeutschland. Jena: Gustav Fischer. Translated in part by Charlisle W. Baskin as Central Places in Southern Germany. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1966.

Corboz, André. 2001. Le territoire comme palimpseste et autres essais. Presented by Sébastien Marot. Besançon: Éditions de l’Imprimeur.

Crumley, Carole. 1979. “Three Locational Models: An Epistemological Assessment for Anthropology and Archaeology.” In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 2: 141–73.

Crumley, Carole. 2005. “Remember How to Organize: Heterarchy Across Disciplines.” In Nonlinear Models for Archaeology and Anthropology: Continuing the Revolution, edited by William W. Baden and Christopher S. Beekman, 35–50. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1980 (1987). A Thousand Plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Escobar, Arturo. 2008. Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes. Durham: Duke University Press.

Escobar, Arturo. 2018. Un autre monde est possible. Des chemins pour les transitions depuis Abya Yala/Afro/Amérique Latine. Translated from Spanish by Claude Rougier. Durham: Duke University Press.

Escobar, Arturo. 2021. “Anthropology, Designing and World-Making.” In Designs and Anthropologies: Frictions and Affinities, edited by Keith M. Murphy and Eitan Y. Wilf, 169–89. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Harari, Yuval Noah. 2024. Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI. London: Fern Press.

Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Jackson, J. B. 1984. Discovering the Vernacular Landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ledeboer, Daaf. 1993. “L’application de la méthode de Banlieues 89 au niveau de la ville entière.” In Taking Sides. Antwerp’s 19th-Century Belt: Elements for a Culture of the City / En marge des rives. La ceinture du XIXe siècle à Anvers: éléments pour une culture de la ville, edited by Pieter Uyttenhove, 282–89. Antwerp: Open Stad.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1950 (1987). Introduction to Marcel Mauss. Translated by Felicity Baker. London: Routledge.

Marot, Sébastien. 2010. L’art de la mémoire. Le territoire et l’architecture. Paris: La Villette.

McCulloch, Warren. 1945. “A Heterarchy of Values Determined by the Topology of Nervous Nets.” Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 7: 89–93.

McIntosh, Roderick J. 2005. Ancient Middle Niger: Urbanism and the Self-Organizing Landscape. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Piron, Sylvain. 2008. L’occupation du monde. Bruxelles: Zones Sensibles.

Ray, Celeste, and Manuel Fernández-Götz, eds. 2019. Historical Ecologies, Heterarchies and Transtemporal Landscapes. London and New York: Routledge.

Remy, Jean, and Liliane Voyé. 1981. Ville, ordre et violence. Formes spatiales et transactions sociales. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Remy, Jean. 1998. Sociologie urbaine et rurale. L’espace et l’agir. Interviews and texts collected by Etienne Leclercq. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Remy, Jean. 2007. Louvain-la-Neuve, une manière de concevoir la ville. Genèse et développement. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

Roberts, Bryony. 2016. Tabula Plena. Forms of Urban Conservation. Zürich: Lars Müller.

Rowe, Colin, and Fred Koetter. 1984. Collage City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sassen, Saskia. 2015. “Centralité. Polarité, nodalité.” In Notions de l’urbanisme par l’usage, edited by Francis Beaucire and Xavier Desjardins, 25–27. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne.

Schulte Beerbühl, Magrit. 2012. “Networks of the Hanseatic League.” In EGO: European History Online. https://www.ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/european-networks/economic-networks/margrit-schulte-beerbuehl-networks-of-the-hanseatic-league.

Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Stevens, Mary Otis, and Thomas McNulty. 1970. World of Variation. Boston: I Press; New York: George Braziller.

Tschumi, Bernard. 1994. The Manhattan Transcripts. London: Academy Editions.

Van den Heuvel, Charles. 2005. De Huysbou: A Reconstruction of an Unfinished Treatise on Architecture, Town Planning and Civil Engineering by Simon Stevin. Amsterdam: Koninklijke Nederlandse Academie van Wetenschappen.

von Humboldt, Alexander. 1850. Views on Nature: or Contemplations on the Sublime Phenomena of Creation with Scientific Illustrations. Translated by E. C. Otté and Henry G. Bohn. London: Harrison and Sons.

Watson, Vanessa. 2009. “‘The Planned City Sweeps the Poor Away…’: Urban Planning and the 21st Century Urbanization.” Progress in Planning 72: 151–93.