Geo-Aesthetics

Related terms: geoaesthetics, geopolitics, Arctic image production, artistic research practice, ecological thinking in practice, non-representationality, post- and decolonial discourses, experimental ethnography

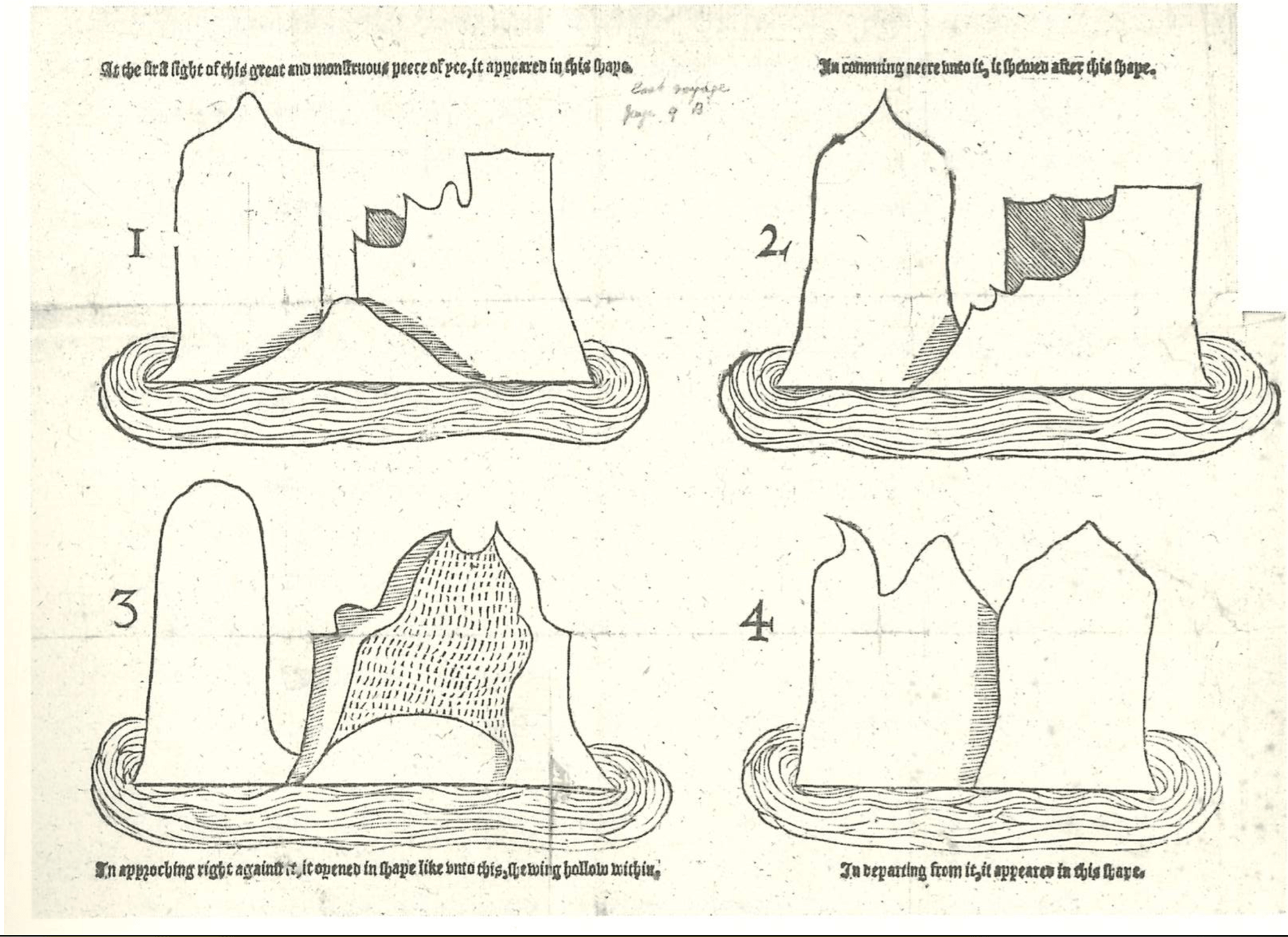

In the late 16th century, a sailor named Thomas Ellis made a woodcut of an iceberg upon a disastrous English expedition headed towards Eastern Greenland. A visual representation of an iceberg made up of four (broken) pieces, appearing as a sort of sequence of a ship’s drift past an iceberg.

Today, centuries later, when media technologies promise high-resolution experiences of faraway places in an instant, Elis’s woodcut appears foremost as a visual record of a European-centred historical past. I encountered the woodcut in art historian Christopher P. Heuer’s examination of the Renaissance imagination of the far North (Heuer 2019). Yet, as Heuer examines, Elis's woodcut manifests an experience of the far North as not just “icy and unpopulated, but also visually and temporally ‘abstract’” (ibid., 60). I suggest that Elis's woodcut succeeds better than any 8K or XR technologies in the present in manifesting icebergs as metaphors of contemplative complexity, or what can be considered a geo-aesthetical condition. Put differently, icebergs are always different, always moving, offering critical perspectives on the “frozen” moment of the representational image itself. As photogenic Arctic features in the context of today’s climate collapse, icebergs are also expressions of a future past. In being visually representative of the Arctic, melting icebergs manifest the threat of an irreversible climate collapse and a future when the Arctic will have melted.

The term ‘geo-aesthetics’ indicates that what connects the two words, ‘geo’ and ‘aesthetics’, is a gap that signals an occupation with how natural environments affect human beings and how human beings express this impact aesthetically. This makes mediation a key term when understood as a process or milieu that is never foreclosed. Assuming moreover, that aesthetic qualities attributed to geographical places are fundamentally relational qualities (that also can be read geopolitically), affect, sensibility and even care become intrinsic to such processes or milieus of mediation. In this sense, the term ‘geo-aesthetics’ designates an aesthetics that. Sensorial experience is situated within frameworks of imagination (Silva 2007) and contextually ingrained in social imaginaries and spheres mediated by technical and affective registers as much as global and institutional layers of policy and ‘capitalist logistics’ (Daugaard, Tygstrup, and Ullerup Schmidt 2024; Harney and Morton 2021). Yet, this makes life as such a kind of mediatic space and geo-aesthetics a matter of how sensorial experience alongside trained enskillment and media-technologies play a role in ascribing aesthetic qualities to geographical places (Mitchell 2015). Affection and passion thrive through global infrastructures as situated qualities conducive to mediation, and more fundamentally in constituting and producing time and place. At stake in a geo-aesthetical appraoch then is a shift from representation (and its politics of “nature,” “culture,” “self,” and “other”) to mediation as a matter of aesthetic interest – or a passionate engagement in certain images concerning a place and in context of a proces. Images of the Arctic, for example.

I have worked with and in the context of Arctic image production for many years. Anecdotes, experiences, archival materials and scientific facts constitute the stuff I manoeuvre with and through, while thinking about the potential of a geo-aesthetical critique of the dominant framework for present Arctic image production. Different from their historical colonial perception as dangerous, hostile and life-threatening, Arctic icebergs have become a widespread symbol of the struggle for humanity’s survival in the climate crisis. (Borm and Chartier 2018; Remaud 2022). In a contemporary context, where economic, geopolitical and neocolonial interests are accentuated as an effect of the Arctic’s decreasing cold and retreating ice – e.g., in new opportunities for the extraction of rare earths, shipping routes via the Northeast Passage, and military-strategic territorial claims – scenic wildernesses and desolate icebergs are promoted as visual representations that appeal to our desire for sublime silence, purity and grandeur (Remaud 2022) in cultural productions of and speculative imaginations about the region’s future(s).

Image production in the Arctic, then, is said to have an urgent impact because the region plays a key role in the cultural imagination of the climate future of the planet and its political and ecological systems, but also because of how images are used to prompt future actions (Demos 2023). Activists' use of imagery to create awareness of and response to the accelerating global climate crisis thus tends to overlap with commercial imagery meant to attract tourists. This is particularly the case with decolonializing processes, e.g., in Kalaallit Nunaat, where investing in tourism is a crucial means towards economic self-reliance and independence.

But scenic and desolate icebergs are also geo-aesthetic clichés that can be traced back to the 19th century romanticization of the Arctic, its imperial narratives and portrayals of the region as a wilderness beyond (European) civilization, where visiting and heroic explorers announced and named Arctic features and thus made them representative and ‘meaningful’ (in a European or Western notion of meaning) (Ryall, Schimanski, and Wærp 2010).

Against this backdrop, however, and in a contemporary context of the Arctic as a hotspot for climate change (Goldberg 2011) as well as for decolonializing processes confronting Western ideologies of knowledge production (Dias and Bak Herrie 2024), the term geo-aesthetics, I suggest, invites us to abandon self-righteous climate crisis rhetoric in favor of more incongruent, situated, and sensitive rhetorics.

So, what does the term imply exactly?

Geo-aesthetics is a neologism combining the terms ‘geography’ and ‘aesthetics.’ The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘geography’ as the study of the earth’s physical features and the interactions of human activity with those features; etymologically, the Greek origin of the word ‘aesthetics’

The concept of geo-aesthetics thus connects postcolonial studies of representation in art (Jensen 2016) with cultural geographers’ preoccupation with how questions of environment, place and geology are brought together in visual artistic practice (Hawkins and Straughan 2015). Think of post-colonial biases towards ‘conventional forms of representation in art’ and how, subsequently, the scope of much practice-based artistic research has been to develop a more integrated critique of colonial and neo-colonial presences in the Arctic. A core concern has been how artworks 'about the Arctic’ can push the boundaries of geopolitical, geohistorical and geoaesthetic approaches through transgressive forms (Jensen 2016). Here I am specifically thinking, together with Jensen (2016), of the Danish-Greenlandic artist Pia Arke’s work in challenging how the Arctic has become accessible and relevant to contemporary art in recent decades. That is, while the Arctic has been ‘opened’ to both neoliberal aesthetic spectacle and social creativity (Heuer 2019, 23), Arctic material, so to speak, has also become a focal point for historical critiques of (early modern) theories of representation and concerning the colonial legacy of information technologies. As effects of Arke’s heterogeneous image-driven practice, her artworks explore the historical and colonial relationship between Kalaallit Nunaat and Denmark as much as its embeddedness in image practices. This, I suggest, speaks to the matter of images in studies of a relationship between art and ecology in a broader sense.

The signals emphasise how knowledge is woven together with cultural imagination and as a result of material thinking operations – operational processes that are embodied, situated and materially structured (Brun 2024). Geo-aesthetical representations of the Arctic are freed of any full meaning.

‘Geo-aesthetics,’ then, actualises media geological methods and STS studies within art and cultural theory (Parikka 2015; Kember and Zylinska 2012), but also so-called geophilosophy (Shapiro 2004). Thus, based on the assumption that there is an overlap between geopolitics, historical colonialism and colonial image practice, a geo-aesthetic approach does not simply indicate geo-political problems through representation. Nor is it delimited to disclosing colonial legacies of geographical representation.At stake in a geo-aesthetical approach, then, is a shift from representation (and its politics of “nature,” “culture,” “self,” and “other”) to mediation as a matter of geopolitical aesthetic interest – or a passionate engagement in certain images in relation to a place and in context of a process.

This, then, has methodological implications: The starting point for analysis must be the embodiment and experience of the representational discourse’s discontent(la Cour 2022). At stake is how to work not with instantiations of predefined categories (Ballestero and Winthereik 2021) – such as say icebergs, ‘the Arctic’ or even ‘nature’ – but to embrace and work from within the gap, so to speak, by developing more relational and temporal forms of the image and of image practices. In my practice, I explore the possibility of such forms and expressions through a process-oriented feminist approach to film practice as archival research. I more explicitly use video-live editing as a method through which representation is negotiated through remediation, to exhibit the site of production as one of both observation and presentation. The urge is to refrain from self-righteous climate crisis rhetoric in favour of more incongruent, situated and sensitive rhetorics where different registers working on each other are exposed and allowed; e.g. conversational processes as forms and expressions anchored in anecdotes, scholarly conversations and personal memories alike. In that sense, live editing expresses an occupation with the axis of time as a gap of potentiality, through an occupation with means of production and distribution in the presentation of an image.

While my practice is far from that of Elis, my interest in his woodcut of an Arctic iceberg in 1578 stems from my search to navigate and theorise a relationship, namely that between the production of an artistic practice and. Understanding the Arctic to be constantly (re)-produced through personal imaginaries alongside industries, institutions and individuals that act to circulate its representations (even if they do not share the same meaning), I consider the effect of artistic practice to be tangles of trajectories, contradictions and disjunctures (Little 2016) that alongside material frameworks of memory (languages, rituals, myths, songs, monuments, institutions) configure collective memory (Halbwachs 1992) and are co-constitutive of the imaginaries through which they – images and imaginations – make collective sense of the past, present and the future (Davoudi and Machen 2022). Images affectively ‘arrest’ us, as anthropologist Kathleen Stewart has it (2003), as they splice with the imaginary capacity of our wider political collective. Hence, the bearing of visual materials about the Arctic on human behaviour, and the anthropogenic effect on the climate.

As biophysical phenomena whose representations are conditioned by human perception, Arctic icebergs, then, exhibit the limited ability of visual representation to match sensory experience in a process of change. Again, I am not talking about a need for 4K, 5K, 8K resolution video and XR as a means to that end. Rather, I am pointing out the capability of recognising a gap, or a lack, a discontent, in the representational discourse. An in-between space free of any full meaning. As a cultural-historical reference in the mediation of ‘Arcticness’ (Kelman 2017), icebergs rather exhibit a limited modernist understanding of aesthetic experience as a neutral and universal sensation, and thus challenge Arctic fantasies of authenticity and universal validity. This includes ideals of the neutrality of icebergs as biophysical phenomena and any general cultural-historical significance of ‘nature’. In other words, to present something to other people is also, simultaneously, to produce it and to live it. Authenticity! The notion of geo-aesthetics has ultimately shaped my idea of live editing as a mode of collapsing the tensions between production and presentation by emphasising the process of living and the Arctic, as Christopher P. Heuer (Heuer and Zorach 2018) has it, as less a finite place than a condition.

References

Ballestero, Andrea, and Brit Ross Winthereik, eds. 2021. Experimenting with Ethnography: A Companion to Analysis. Experimental Futures. Durham: Duke University Press.

Borm, Jan, and Daniel Chartier, eds. 2018. Le froid: adaptation, production, effets, représentations. Collection Droit au pôle. Québec (Québec): Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Brun, Elisabeth. 2024. “Reconfiguring the Mountain: A Topographical Approach to Aesthetics in an Age of Time- and Place-Illiteracy.” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 33 (67).

Cour, Eva la. 2022. Geo-Aesthetical Discontent: Svalbard, the Guide and Post-Future Essayism. 90. Gothenburg: ArtMonitor.

Daugaard, Solveig, Frederik Tygstrup, and Cecilie Ullerup Schmidt, eds. 2024. Infrastructure Aesthetics. Concepts for the Study of Culture (CSC) 9. Berlin Boston: De Gruyter.

Davoudi, Simin, and Ruth Machen. 2022. “Climate Imaginaries and the Mattering of the Medium.” Geoforum 137 (December):203–12.

Demos, T. J. 2023. Radical Futurisms: Ecologies of Collapse, Chronopolitics and Justice-to-Come. London: Sternberg Press.

Dias, Tobias, and Maja Bak Herrie. 2024. “Questionnaire on Aesthetics in the Age of Unreason.” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 33 (67).

Goldberg, Mark Leon. 2011. “A Chilling Warning from a ‘Hot Spot’ in Climate Change.” UN Dispatch (blog). June 29, 2011.

Halbwachs, Maurice. 1992. On Collective Memory. Translated by Lewis A. Coser. The Heritage of Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Morton. 2021. “All Incomplete.” Minor Compositions (blog). 2021.

Hawkins, Harriet, and Elizabeth Straughan, eds. 2015. Geographical Aesthetics: Imagining Space, Staging Encounters. Farnham, Surrey, UK; Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Heuer, Christopher P. 2019. Into the White: The Renaissance Arctic and the End of the Image. Brooklyn, New York: Zone Books.

Heuer, Christopher P., and Rebecca Zorach, eds. 2018. Ecologies, Agents, Terrains. Clark Studies in the Visual Arts. Williamstown, Massachusetts: Clark Art Institute.

Jensen, Lars. 2016. “Approaching a Postcolonial Arctic.” KULT - Postkolonial Temaserie 14 (November): 49–65.

Kelman, Ilan, ed. 2017. Arcticness. UCL Press.

Kember, Sarah, and Joanna Zylinska. 2012. Life After New Media: Mediation as a Vital Process. MIT Press.

Little, Kenneth. 2016. “Belize Ephemera, Affect, and Emergent Imaginaries.” In Tourism Imaginaries: Anthropological Approaches, edited by Noel B. Salazar and Nelson H. H. Graburn, First paperback edition. New York: Berghahn Books.

Malpas, Jeff. 2018. Place and Experience: A Philosophical Topography. Second edition. New York: Routledge.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 2015. Image Science: Iconology, Visual Culture, and Media Aesthetics. Chicago: The Univ. of Chicago Press.

Parikka, Jussi. 2015. A Geology of Media. Electronic Mediations, volume 46. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press.

Remaud, Olivier. 2022. Thinking like an Iceberg. Translated by Stephen Muecke. English edition. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Ryall, Anka, Johan Schimanski, and Henning Howlid Wærp, eds. 2010. Arctic Discourses. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Shapiro, Gary. 2004. “Territory, Landscape, Garden: Toward Geoaesthetics.” Angelaki 9 (2): 103–15.

Silva, Denise Ferreira da. 2007. Toward a Global Idea of Race. Borderlines 27. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Stewart, Kathleen. 2003. “Arresting Images.” In Aesthetic Subjects: Pleasures, Ideologies, and Ethics, edited by Pamela Matthews and David McWhirter, 431–48. University of Minnesota Press.