Ecological Design (Architecture)

Related terms: bioclimatics, ecology, hyperobject, niche, sustainability.

‘Oekologie’ was coined by Ernst Haeckel in 1866 to describe the relationship between the animal and its organic and inorganic environment. The word derives from the Greek oikos, meaning household, home, or dwelling. In everyday discourse, the term ‘ecology’ is often used to refer broadly to the environment, natural systems, or sustainability. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ecology refers both to the branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings, and more broadly to “the study of the interaction of people with their environment” (Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “ecology”).

The term ‘ecological design’ was coined by Sim van der Ryn and Stuart Cowan in their 1996 book of the same title, defined as: “any form of design that minimises environmentally destructive impacts by integrating itself with living processes” (Van der Ryn and Cowan 1996, 18). Today, according to ecological design scholar Lydia Kallipoliti, the definition of the term is multifarious. In her Histories of Ecological Design: An Unfinished Cyclopedia, Kallipoliti summarizes the term’s various meanings to include: “the restitution of moral values in design thinking, to revive an archaic humanist discourse; the substitution of ‘performance’ for ‘function,’ in the hope of restoring a lost modernist and positivist ethos; the post-structuralist denunciation of environmental improvement; and the critical recognition of waste and pollution as generative potential for design” (Kallipoliti 2024, 19).

This entry will chart the development of the term and examine its relevance in the architecture and design disciplines, as challenges to the sub-discipline of sustainability lead to a renewed search for the meaning and relevance of ecological design today.

To move from general understandings to the specific stakes of contemporary ecological design, especially as they are engaged within architectural discourse and the environmental humanities, it is necessary to examine how the concept of ecology has evolved. What follows is not simply a genealogy, but a means of tracing how ecological thinking has moved across disciplines, from biology to design, and how this movement shapes current claims about what ecological design is, or ought to be, today.

Ecology

In On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin articulated his theory of evolution, in which small changes in combination with environmental fitness resulted in evolutionary advancement. “Variations,” he wrote, “however slight and from whatever cause proceeding, if they be in any degree profitable to the individuals of a species, in their infinitely complex relations to other organic beings and their physical conditions of life, will tend to the preservation of such individuals, and will generally be inherited by the offspring” (Darwin 1859, 48). These physical conditions (climatic, material, parasites, predators…) are a mesh that is tied into the animal’s specifics and from which the animal cannot be separated.

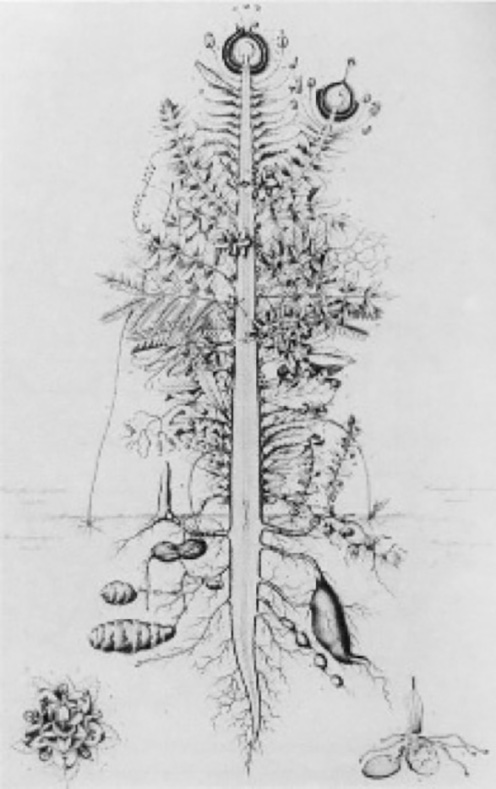

Darwin’s insights emerged from earlier contributions to natural history. Theophrastus had described the traits of various plant species, concerning their surroundings: soil, moisture, and sunlight (Theophrastus, c. 350–287 BCE [1916]). Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had proposed the Urplanze, an ideal plant that morphs in response to climatic shifts (Von Goethe 1790, 6). Crucially, where Goethe’s responsive morphology was Platonic – it had an ideal form – Darwin’s was unmotivated and without an original, only existing as an ongoing series of relationships between things.

This network, this set of relations between the animal and the environment, is what Ernst Haeckel, a few years after Darwin’s publication, would call Oekologie: “the comprehensive science of the relationships of the organism to its surrounding environment, where we can include, in the broader sense, all ‘conditions of existence’” (Haeckel 1866, 286). Despite an alternative definition proposed in 1892 by Ellen Swallow Richards which would tie the term to home economics (Clarke and Swallow 1973, 55), the British Medical Journal initially defined ‘oekology’ as a branch of morphology and physiology resting on the “exploitation of the endless phenomena of animal and plant life as they manifest themselves under natural conditions” (British Medical Journal 1873, 384).

In 1917, D’Arcy Thompson’s diagrams, depicting species and genera through continuous and simple geometric transformations, rendered the biological development of physical forms with external forces graphically legible. For example, in his “Evolution of body form” diagram, Thompson overlayed a grid on silhouettes of two pairs of fish (Argyropelecus Olfersi/Sternoptyx diaphana, and Diodon/Orthagoricus) to demonstrate how each might be considered a mathematical transformation of the other.

The grid, which represents the forces of deformation across species, suggested an underlying ordering system in the natural world. ‘Force,’ as understood by Thompson, was: “the appropriate term for our conception of the causes by which these forms and changes of form are brought about” (Thompson 1917, 11). However, while many environmental factors (gravity, energy, motion) were mentioned, and Thompson noted that transformations may depend on various phenomena, “from simple imbibition of water to the complicated results of the chemistry of nutrition,” environmental forces were not specifically mapped in the transformations (Thompson 1917, 10).

Architectural Ecologies

Architecture, as a material transformation of the earth, has long had an affinity with natural systems. In Vitruvius’ Ten Books on Architecture, climatic variation is linked to bodily variation, and by extension, to architectural form. While Vitruvius ultimately prioritised order and symmetry, his treatise opened an early precedent for considering architecture as a response to environmental variation (Vitruvius 1960 [1521], 170).

Taxonomic thinking – classifying forms by type, like Buffon or Linnaeus did with species – also shaped architectural theory. Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand and others proposed systematic methods for deriving architectural form from geometric rules, an abstraction that inevitably erased the environmental context. The 1830s witnessed a deeper entanglement. Inspired by naturalist Georges Cuvier, the “Romantic Pensionnaires”, including Labrouste, LeDuc, Vaudoyer, and Duban, rejected the architecture of the ancients that had been taught to them at the École de Beaux Arts in favour of an architecture derived from functional adaptation via technology. They preferred gothic architecture, which they believed was better aligned with nature. For Vaudoyer, the ribbed vaults of the Gothic cathedral spoke of branching trees in the forest (Vaudoyer 1839, 336). This was more than an analogy – it was an effort to construct buildings in alignment with the laws of nature, an early precedent for ecological design as both philosophical and structural.

Louis Sullivan, in the late nineteenth century, circled back to nature as an analogy for architecture as he argued for function over form:

Whether it be the sweeping eagle in his flight or the open apple-blossom, the toiling work horse. The blithe swan, the branching oak, the winding stream at its base, the drifting clouds, over all the coursing sun, form ever follows function, and this is the law. Where function does not change, form does not change… (Sullivan 1896, 111).

In the mid-twentieth century, theorists and practitioners like Frederick Kiesler, Frank Lloyd Wright, and James Marston Fitch continued this lineage. Kiesler’s correalism proposed a theory of mutual interaction between human and environment (Kiesler 1939, 61). Wright emphasised harmony with materials and site (Lloyd Wright 1939), and Fitch framed architecture as a third environment mediating between body and climate (Fitch 1948).

Beginning in the 1960s, ecological awareness gained broader cultural traction. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring drew awareness to environmental harm caused by pollution (Carson 2002). Arne Naess developed the concept of a “deep ecology,” in which all living beings were considered to be inherently equal in value (Naess 1973). Lydia Kallipoliti has written widely on the emergence of this movement following the publication of photographs of Earth from the 1968 Apollo 8 mission. The view of the planet from space, she wrote, allowed the world to see itself as “a closed and ill-managed planet heading toward evolutionary bankruptcy, while arguing the modern science offered the most faithful account of civilizational values” (Kallipoliti 2024, 109).

The notion of design with the environment mushroomed under various titles: green, sustainable, bioclimatic, and environmental. In 1963, Victor Olgyay published Design with Climate: Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism (Olgyay 1963), which linked architecture with technology, biology, and climatology and described methodologies for climate-responsive design. Figures like Ian McHarg, John McHale, Reyner Banham, and Buckminster Fuller promoted design that replicated nature and understood ecological design broadly: as planetary design as much as the design of an object or space. Ian McHarg’s Design with Nature (1969) presented a pioneering approach to landscape architecture and planning based on ecological principles, advocating for the integration of natural systems-geology, hydrology, and vegetation – into the design process to create more sustainable and resilient environments. Also in 1969, Reyner Banham published The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment (Banham 1969), which argued for the inclusion of environmental systems into architecture proper and set the stage for a more technological modus operandi. John McHale’s The Future of the Future suggested that “humans had enlarged their ecological niche to include the whole planet” (McHale 1969, 17). McHale drew sectional diagrams from the Earth’s core to the sun to include the affected ecology in any object. From the inner earth to outer space, these “Superscale Survey” drawings zoomed out to consider how any act could affect multiple layers of the planet and beyond.

McHale’s next book, Ecological Context (McHale 1970), was a manifesto for ecological design understood more holistically and politically. McHale argued for adopting design as the solution for the complex problems of the planet. The implication for architecture and environmental humanities alike is profound: design is never isolated but remains part of a vast, interrelated mesh of social, political, and ecological structures.

The 1990s brought critiques of environmental architecture, which was accused of being nothing more than ‘greenwashing’: the image of sustainability without the performance. Certifications like LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) came under attack for maintaining a status quo and corporate values, rewarding gestures over meaningful impact. Critics, including myself, saw sustainable hi-tech systems applied only after fundamental yet unsustainable moves had been made, as a “remedy” to the problems created by aesthetic choices (O’Donnell 2016, 590). Glass towers like Foster and Associates’ 30 St. Mary Axe – commonly known as The Gherkin – garnered criticism for labelling themselves ‘sustainable’ while many of the systems were countering aesthetic design choices: e.g. fritted glass limiting heat gain in windows when the choice of glass was fundamentally unsustainable in many ways. Jonathan Massey pointed out that if the operable windows of the building were not used, “30 St. Mary Axe is not a green tower but an energy hog.” He continued: “It is striking, then, that the building has been a critical and financial success despite its failure to realise one of the headline claims made about its design” (Massey 2014, 17). Similarly, Michelle Addington criticised the tautological logic of ‘smart facades,’ claiming that they solved problems created by design choices themselves (Addington 2015, 60). In the 1990s, it seemed to many that, despite the best intentions, ecological design had been co-opted by capitalist systems and aesthetic tropes.

At the same time – and independently, since the branches of theory and sustainability had become disconnected – digital architecture was embracing evolutionary processes. Greg Lynn’s “Embryological Houses” used terms like ‘broods’ and ‘species’ (Lynn 2003) to describe adaptive and responsive architectural form. Lynn argued for an architecture that, in its design process, was less understood as an isolated object and more considered as being in dialogue with forces that shape it from the exterior. He proposed that “the spatial organism” was no longer understood as static and independent of external forces, but rather as a sensibility continuously transforming through its internalisation of outside events” (Lynn 2003, 39). Invoking D’Arcy Thompson’s transformative diagrams, however, Lynn propagated the same omission that had befallen Thompson, and that was to suppress the role of context in the representation of iterative design. While both mentioned external forces and cited examples, neither the forces nor their causations appeared as a component of the representations, and they remained, for the most part, an abstraction. As a result, while digital design exploded at the turn of the twenty-first century, the ideas of evolutionary thinking that went alongside it were rather one-sided: the ‘organism’ (the design object) evolved, but the forces motivating that evolution remained unrepresented and neglected, entirely separate from the organism affected.

As the new millennium approached, theory engaged questions of nature, agency, and structure. The term ‘Anthropocene’ came to define an epoch of human transformation of the planet. Deleuze and Guattari's book A Thousand Plateaus introduced the concept of the “rhizome” to describe non-hierarchical, interconnected networks: “connections between semiotic chains, organisations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences and social struggles” (Deleuze and Guattari 1980, 7). More recently, Timothy Morton defined the term ‘hyperobject’ as “objects (that) entangle one another in a crisscrossing mesh of spacetime fluctuations” (Morton 2013, 28).

In an evolution from the critiqued glass towers of the 1990s, contemporary architecture has shifted away from the language of ‘sustainability,’ which favors the technical aspect of the approach, towards the term ‘ecological,’ which aims to shift away from pragmatic problem-solving toward the consideration of the building as an agent within a broader ecosystem, including not just environmental but also social, cultural, and temporal dimensions.

Some recent architectural practices are shifting toward this definition, but they still have a way to go in developing a new language of ecological design. Contemporary projects have moved beyond attempts to mitigate harm, aiming instead to create benefit: they promote energy production, material circularity, and social sustainability. The Powerhouse Brattørkaia in Norway (architects: Snøhetta, 2019), for example, is one of the world’s northernmost energy-positive buildings. Generating more energy than it consumes over its lifetime, the building prioritises solar exposure, local materials, and long-term adaptability. Yet, even here, questions persist about carbon embedded in construction and whether ‘energy-positive’ metrics adequately account for broader ecological entanglements. The Forest School in India (architects: Sameep Padora & Associates, 2021) is built using local stone, lime mortar, and traditional construction techniques. The design prioritises ventilation, thermal mass, and shading, allowing the functioning of the space without mechanical cooling. What makes it significant is its deeply contextual and low-tech response to climate and culture, offering a model of ecological architecture where social and pedagogical functions are inseparable from environmental stewardship. The Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design in the USA (Miller Hull Partnership 2020) generates all its energy on-site, captures and treats water, and is constructed with reclaimed and non-toxic materials. It embeds social equity goals – such as local workforce training and inclusive educational programming – underscoring that ecological design must also engage with environmental justice. It exemplifies the environmental humanities principle that ‘sustainability’ is not just technical and material but cultural and ethical.

These examples reveal a spectrum – from symbolically rich, culturally embedded forms to high-tech sustainability models – and underscore that ecological design cannot be reduced to a checklist. Its meanings shift with context, intention, and scale. Such projects are not endpoints but starting points for reflection on what it means to build ethically and imaginatively in a destabilised world. At the same time, contemporary ecological architecture has yet to fully embrace its identity as a language, a vessel for communication of theoretical ideas that promote thinking about interconnectedness beyond the pragmatic. That is to say, beyond being ecological, how can a building communicate its ecological-ness in a way that launches a new architectural genre? In other words, what does a world that truly prioritises ecological design look like?

French critic Frédéric Migayrou has argued that “ecology as a science is based on the negation of all things natural” (Migayrou 2003, 22). In other words, ecological design signals a fundamental paradox: ecology, as a science, presupposes the disappearance of ‘nature’ as an untouched or stable referent. In this view, ecological design must operate within a world where ‘nature’ is already technologically and culturally constructed, raising critical questions about whether ecological design can ever be fully pragmatic or sustainable, and whether it remains trapped in ideological abstraction. Yet for Lydia Kallipoliti, ecology within the discipline of architecture marks not an end, but a turn. Ecological design, she posits, is “not a case of burdensome maintenance, but one of care; a means of apprehending the world via the raw, visceral nature of beings entangled in planetary climates” (Kallipoliti 2024, 21). Drawing from feminist thinkers like Maria Puig De la Bellacasa, Kallipoliti frames the idea that care, as an ethical framework, may “challenge dominant systems and ideologies through the dimensions of affection, sensitivity and physical work,” so that architects and designers could operate “within the built world as if it were an ecosystem” (Puig De la Bellacasa 2017, 3). In this view, ecological design is not simply the application of scientific knowledge to material practice but a way of dwelling critically, carefully, and responsibly in the world. As Kallipoliti concludes, ecological design begins with “a reconceptualisation of the world as a complex system of flows rather than a discrete compilation of objects” (Kallipoliti 2024, 23).

The ecological design project is unfinished. Its historical entanglement with science, aesthetics, and philosophy reveals a broader cultural shift toward understanding built environments as embedded, situated, and systemic. For the environmental humanities, ecological design becomes a site for exploring how we live and design with interconnectedness.

The implications are urgent. Ecological design asks not just how to mitigate harm but how to reconceive relations among humans, materials, climates, and economies. Its difficulty lies in its interdisciplinarity: it crosses science, ethics, art, and politics. But therein lies its strength. We must stay with its trouble, acknowledge its failures, and push for forms of practice that embrace both performance and care. The future of ecological design is not only a technical problem, but a cultural and ethical one.

References

Addington, Michelle. 2015. “Smart Architecture, Dumb Buildings.” In Building Dynamics: Exploring Architecture of Change, edited by Branko Kolarevic and Vera Parlac, 111–22. New York: Routledge.

Andrewartha, Herbert G., and Louis C. Birch. 1954. The Distribution and Abundance of Animals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Banham, Reyner. 1969. The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Barber, Daniel. 2014. “The Thermoheliodon.” ARPAPress Journal 1 (May 15).

British Medical Journal. 1873. “Science and Practice.” BMJ 1 (665).

Carson, Rachel. (1962) 2002. Silent Spring. London: Penguin.

Clarke, Robert, and Ellen Swallow. 1973. The Woman Who Founded Ecology: The Story of Ellen Swallow Richards. Chicago: Follett Publishing Company.

Darwin, Charles. (1859) 2010. On the Origin of Species. 6th ed. Stilwell, KS: Digireads Publishing.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. (1980) 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Fitch, James M. 1948. American Building: The Forces That Shape It. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Geddes, Patrick. 1915. Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and to the Study of Civics. London: Williams and Norgate.

Haeckel, Ernst. 1866. Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Vol. II. Berlin: Georg Reimer.

Kallipoliti, Lydia. 2024. Histories of Ecological Design: An Unfinished Cyclopedia. New York: Actar.

Kiesler, Frederick. 1939. “On Correalism and Biotechnique: A Definition and Test of a New Approach to Building Design.” Architectural Record 86 (September): 58–63.

Lloyd Wright, Frank. 1939. An Organic Architecture: The Architecture of Democracy. London: RIBA.

Lynn, Greg. 1998. “Multiplicitous and In-organic Bodies.” In Folds, Bodies and Blobs: Collected Essays, 87–106. Brussels: La Lettre Volée.

Macarthur, John. 2007. The Picturesque: Architecture, Disgust and Other Irregularities. New York: Routledge.

Massey, Jonathan. 2014. “Risk Design.” Grey Room 54 (Winter): 6-33.

McHale, John. 1969. The Future of the Future. New York: George Braziller.

McHale, John. 1970. The Ecological Context. New York: George Braziller.

McHarg, Ian. 1969. Design with Nature. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Migayrou, Frédéric. 2003. “Extensions of the Oikos.” In Archilab’s Earth Buildings: Radical Experiments in the Architecture of the Land, edited by Marie-Ange Brayer and Béatrice Simonot, 16–27. London: Thames and Hudson.

Morton, Timothy. 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Naess, Arne. 1973. “The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement: A Summary.” Inquiry 16 (1–4): 95–100.

O’Donnell, Caroline. 2015. Niche Tactics: Generative Relationships Between Architecture and Site. New York: Routledge.

O’Donnell, Caroline. 2016. “The Order of Order: Towards an Environmental Functionalism.” In 103rd ACSA Annual Meeting Proceedings, The Expanding Periphery and the Migrating Center, edited by Lola Sheppard and David Ruy, 423–27. Washington: ACSA Press.

Olgyay, Victor. 1963. Design with Climate: Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Oxford English Dictionary Online. s.v. “ecology.” Oxford University Press. Accessed April 30, 2025.

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Sullivan, Louis H. (1896) 1988. “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered.” In Sullivan: The Public Papers, edited by Richard Twombly, 103-112. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sullivan, Louis H. (1979) 1988. “Function and Form.” In Kindergarten Chats and Other Writings, 13–22. New York: Dover. Reprint of Interstate Architect and Builder.

Theophrastus. (ca. 350–287 BCE) 1916. Historia Plantarum. Translated by Arthur Hort. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Thompson, D’Arcy Wentworth. (1917) 1961. On Growth and Form. Edited by John Tyler. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vaudoyer, Léon. 1839. “Études d’architecture en France.” Magasin Pittoresque 7: 336.

Van der Ryn, Sim and Stuart Cowan. 1996. Ecological Design. Washington D.C.: Island Press.

Von Goethe, Johann Wolfgang. (1790) 2009. The Metamorphosis of Plants. Edited and translated by Gordon L. Miller. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vitruvius Pollio, Marcus. (1521) 1960. The Ten Books on Architecture. Translated by Morris Hicky Morgan. New York: Dover.