Disaster risk

Gosia Warrink

Related terms: complex emergencies, disaster risk governance, disaster risk reduction (DRR), early warning system, exposure, fragility, hazard, vulnerability, resilience, risk anticipation, social justice, uncertainty, wicked problems

The philosopher Hans Blumenberg, in his theory of non‑conceptuality (Unbegrifflichkeit), explores the unease evoked by terms that fail to grasp what moves or threatens us, or terms that elude us by virtue of their abstraction. Terms, Blumenberg maintains, operate through what he describes as “action at a distance” (actio per distans, Blumenberg 2007, 13): they offer orientation by substituting – symbolically and pragmatically, across space and time – for the physical presence or idea of what they name. In that sense, a term resembles a hunting trap – it stakes out the terrain within which meanings are to be captured. Yet in moments of existential uncertainty – particularly during crises or disasters – abstract terms come under pressure, caught between semantic vagueness and the demand for clarity that becomes crucial in exceptional circumstances. Blumenberg’s thesis is that humans act in anticipation. Thus, terms become tools of projection – means of imagining what lies, or may lie, ahead.

This projective capacity of terms is especially relevant in the case of disaster risk, a key term in international disaster risk reduction. The notion of disaster risk opens a semantic field of technical terms used by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) – including disaster risk, disaster risk assessment, disaster risk governance, disaster risk information, disaster risk management, and disaster risk reduction. Related terms such as disaster, hazard, exposure, vulnerability, and capacity are likewise directly or indirectly linked to disaster risk.

Disaster risk refers less to a concrete event than to the potential occurrence of one. According to the UNDRR, it is defined as “the potential loss of life, injury, or destroyed or damaged assets which could occur to a system, society or a community in a specific period of time, determined probabilistically as a function of hazard, exposure, vulnerability and capacity” (UNDRR 2017).

The term interweaves knowledge and planning with normative expectations, bundling narratives of risk, responsibility, and social vulnerability. It is not a neutral analytical instrument, but a politically and contextually shaped interpretive framework that seeks to render the unpredictable calculable – and in doing so, reveals its own ambiguity. Positioned between calculation and uncertainty, between governance and emotion, disaster risk delineates a field in which both existential threats and questions of power are negotiated.

This text approaches disaster risk from both a terminological and design-oriented perspective.

Catastrophe without event: on the distinction between terms

The UNDRR draws a clear distinction between the event – the disaster – and the conditions under which it may occur. A disaster is defined as “a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society at any scale due to hazardous events interacting with conditions of exposure, vulnerability and capacity, leading to one or more of the following: human, material, economic and environmental losses and impacts” (UNDRR 2017). Disasters are therefore not merely natural occurrences; they emerge from the interplay of structural risks.

Central to this understanding is the differentiation between intensive and extensive disaster risk, as defined by UNDRR. In practice, however, additional crisis contexts such as “complex emergencies” arise, which also challenge conventional risk categories: The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) defines complex emergencies as “multifaceted humanitarian crises” involving conflict-related breakdowns in governance and basic services, requiring a coordinated international response that exceeds the capacity of any single agency; such crises have particularly severe impacts on women and children and demand integrated, multi-sectoral interventions (OCHA 2004, 6). Within UNDRR terminology, such contexts are often addressed through the interrelated terms “affected” and “vulnerability”.

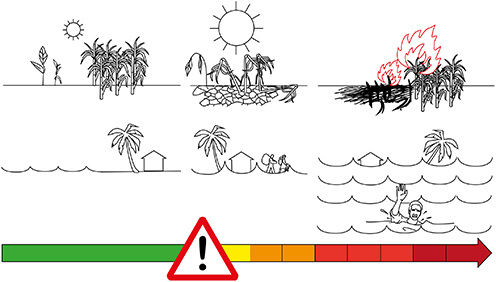

Intensive disaster risk refers to the risk of rare but highly destructive events – such as earthquakes, tsunamis, or large-scale fires – that have severe impacts on densely populated and vulnerable areas. Extensive disaster risk, by contrast, designates frequent, locally confined events such as floods or landslides, whose cumulative effects are often underestimated. This risk is exacerbated by poverty, environmental degradation, and informal settlement patterns.

The Sendai Framework (2015–2030) emphasises a shift in focus: rather than the hazard or the disaster event itself, it places central importance on the enabling conditions – and thus on proactive risk reduction. (UNISDR 2015)

Disasters are crises that are often socially produced: “They are made by people who fail to adequately address the risks,” as communication theorist Jürgen Schulz (2022, 74) puts it. And anthropologist Anthony Oliver‑Smith (1999) emphasises that vulnerability of groups and individuals often matters more than the actual hazard in shaping disaster outcomes. To reduce disaster risk, therefore, is also to pursue social justice.

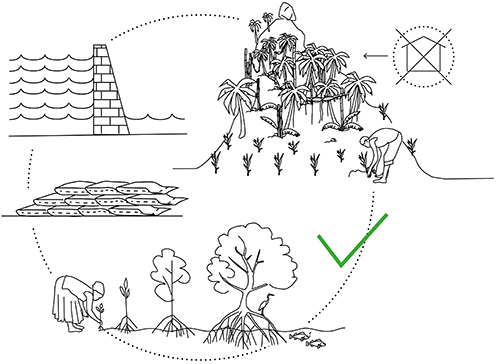

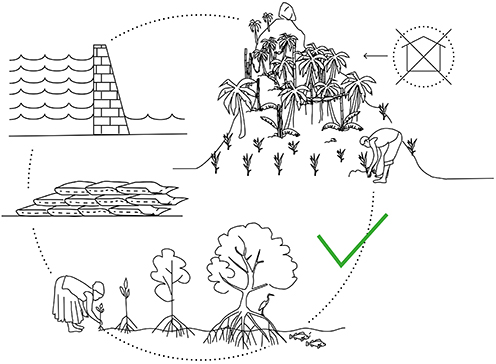

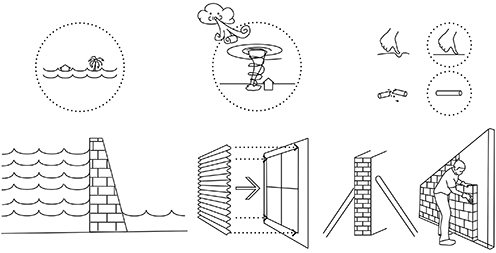

Disaster risk reduction terminology: a project for Sierra Leone

In 2021, I worked as a graphic designer on a social design project for Sierra Leone. In collaboration with NGOs such as the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) Sierra Leone and Bread for the World, local communities, and researchers and translators from the Centre for Translation Studies and Intercultural Crisis Communication at University College London (UCL), the aim was to translate 38 English UNDRR terms and definitions – including vulnerability, capacity, resilience, early warning system, and disaster risk – into five West African languages (Kono, Krio, Limba, Mende, and Themne), as well as into visual symbols, and to compile them in a glossary (UCL 2021). The goal was to make the terms easily accessible to local populations and thereby strengthen disaster literacy and community resilience in the context of disaster risk. For the visualisation of the terms “intensive disaster risk” and “build back better”, the major fire in the Susan’s Bay slum in Freetown in 2021 (Macarthy and Kamara 2021) played a central role: More than a thousand people lost their homes while the fire service was unable to access large areas due to the dense, informal settlement structures. To illustrate this case, the vulnerable, temporary slum environment was contrasted with more stable materials and preferred construction methods, using comparative imagery to highlight the risks of dense informal settlements and the advantages of safer alternatives.

In my understanding, (graphic/artistic) design is also a politically and ethically engaged practice of envisioning (see Banz 2016; von Borries 2017). It is transdisciplinary in nature and cannot be reduced to its aesthetic or formal qualities. The project thus became a profound socio-aesthetic investigation into the meanings and representations of terms and their anchoring within the tensions between multilingualism, cultural diversity, and approaches to decolonising language and thought.

Linguistic diversity, a central element of Sierra Leone’s cultural identity, became a critical risk factor during the Ebola outbreak between 2014 and 2016, where the lack of translations led to misinformation, mistrust, and delayed responses. Since then, multilingual communication has increasingly been understood as a precondition for societal resilience – not least because access to comprehensible and culturally appropriate information can be a matter of life and death (see Federici and O’Brien 2020; Pickering et al. 2023).

The anthropologist Paul Richards analysed the Ebola crisis in West Africa and concluded that it was not solely the medical-technological or logistical apparatus of international actors that helped contain the epidemic, but in fact primarily the local knowledge embedded in everyday practices and cultural routines – a “people’s science” (Richards 2016, 6), rooted in social proximity, trust, and improvisational skill. For example, traditional burial practices were not abandoned but adapted to reduce the risk of infection. Another example was people using raincoats worn backwards or plastic bags as improvised protective clothing.

In engaging with the UNDRR terminology project, it became clear that the understanding of “risk” is neither a scientifically fixed nor a statistically neutral measure – rather, it is contextually coded and subject to communicative negotiation. How, for instance, can one visually distinguish between a natural hazard and a human-induced disaster when, in everyday language, both are subsumed under the same interpretive framework – namely as hazards? And how can exposure or residual risk be meaningfully visualised when there is no clear visual equivalent for systemic risk – yet tangible memories exist of the 2017 mudslide in Freetown (see Musoke et al. 2020), where flash floods swept away hillside homes in areas made more vulnerable by deforestation and informal construction? Mitigation – defined by UNDRR as “the lessening or minimising of the adverse impacts of a hazardous event” – represents one possible response to such localised disaster scenarios. In the illustration developed for this term, a reforested hillside serves as a visual metaphor for proactive risk reduction.

In this context, I came to understand that it is often the local chiefs (traditional leaders) who convey risk-relevant information – provided it is understood, accepted, and implemented (see Rogers 1962). Likewise, “town criers” (traditional messengers who publicly announce information by calling it out in communal spaces) play a crucial role in early warning structures across West Africa.

To grasp how differently visual associations function in Sierra Leone, particularly from a Eurocentric perspective, one needs only consider the following: In Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, there were (as of 2021) only two traffic lights. Thus, a colour-coded warning system based on traffic light symbols fails in this context, as the visual code is not rooted in local visual culture.

Such insights shifted the design focus towards the interconnected semantics of rebus-like symbolic compositions that enable visually associative interpretation. For example, the term “retrofitting” was illustrated in the visual material developed for the project through a composite image that combined a flood barrier with rising water levels, corrugated metal shielding windows from hurricanes, and reinforced walls made of strong bricks.

The term “prevention”, as established during the Ebola crisis, was illustrated by hands being washed with boiled water and chlorine tablets placed next to a water bucket – an image deeply embedded in the collective memory from that period. “Disaster risk”, in this sense, had to be translated into a locally grounded visual world, where the lived reality of Sierra Leone provided a context (Blumenberg describes this as “reality as a constitutive context” [Blumenberg 1969, 13]).

Communication as a risk determinant

An often underestimated aspect in the context of disaster risk reduction is the role of communication. Jürgen Schulz even states: “Without communication, there are no crises” (Schulz 2021). This is not merely a matter of media logic, but also one of language politics. Risk communication always operates within the tension between the transmission of information and the construction of meaning (Luhmann 1971; Schulz 2021). The present-day “security society” (Schulz 2022) generates terms such as crisis, danger, or risk – terms that suggest clarity where in fact ambiguity prevails. Schulz refers to a study by Barry Turner and Nick Pidgeon, who analysed 84 disasters in the United Kingdom and concluded that each resulted from human error – specifically from failures to recognise or appropriately assess existing risks and their potential consequences (Turner and Pidgeon 1978).

Risks, therefore, do not only arise from the event itself, but also from its systematic denial, miscalculation, normalisation, or miscommunication.

The World Disasters Report (IFRC 2018) highlights a structural problem in humanitarian response: Despite the linguistic diversity of affected regions, coordination and communication are often conducted in international lingua francas such as English – frequently without regard for local languages or literacy levels. Data on actual language use are lacking, translation resources are scarce, and the responsibility for comprehensibility is often delegated to untrained individuals from the affected communities. The 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic thus also became a “language crisis” (Richards 2016): Public health information was disseminated predominantly in English or French, although more than 90 languages are spoken in the affected areas, and in Sierra Leone, only around 13 % of women understand English (IFRC 2018). Without reliable and multilingual communication, structural exclusion is inevitable.

The principle of “Leaving No One Behind” – first articulated in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN 2015) – has also shaped the humanitarian approach of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC 2018). It can only be effective if communication is designed to be barrier-free, locally intelligible, and culturally appropriate – otherwise, entire population groups remain systematically excluded (cf. Federici et al. 2021; Pickering et al. 2023).

Risk as a space of possibility

Disaster risk is more than a term – it is a space of possibility in which societies negotiate their conceptions of threat, security, and the future. Between hazard and resilience, between governance and design, between language politics and responsibility, the term marks a nexus of societal negotiation: Who bears risk? Who has the authority to name it? And how can the anticipation of catastrophe become a space for just transformation?

In the Environmental Humanities, disaster risk denotes a zone of overlap between knowledge and interpretation: It links technical expertise with cultural understanding, translation with imagination, and design with ethics – thus enabling an interdisciplinary approach. The term aims at governance while simultaneously revealing how any form of planning must coexist with uncertainty. Precisely for this reason, the right to information is increasingly seen as a cornerstone of disaster justice: Those without access to clear and comprehensible language remain excluded from preparedness, protection, and participation (IFRC 2018).

What remains is the tension between the desire for clarity and the reality of the incalculable. Disaster risk points to this in-between space: a condensation of what cannot be fully grasped but can nevertheless be shaped. It is in this sense that the sociologists Bernd Sommer and Harald Welzer outline an understanding of transformation design that conceives of the future not as a reaction to crisis, but as a cultural practice of envisioning. Here, the question is not only how we calculate risk, but how we shape the future – “by design or by disaster?” (Sommer and Welzer 2014, 11)

References

Banz, Claudia. 2016. Social Design. Gestalten für die Transformation der Gesellschaft. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Blumenberg, Hans. 1969. “Wirklichkeitsbegriff und Möglichkeit des Romans.” In Poetik und Hermeneutik I: Nachahmung und Illusion, edited by Hans Robert Jauß, 9-27. Munich: Wilhelm Fink.

Blumenberg, Hans. 2007. Theorie der Unbegrifflichkeit. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Borries, Friedrich von. 2016. Weltenentwerfen. Eine politische Designtheorie. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Clement, Viviane, Kanta Kumari Rigaud, Alex de Sherbinin, Bryan Jones, Susana Adamo, Jacob Schewe, Nian Sadiq and Elham Shabahat. 2021. Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Coombs, W. Timothy. 2011. Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing, and Responding. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Federici, Federico M., and Sharon O’Brien. 2020. Translation in Cascading Crises. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Federici, Federico M. 2021. Launching the UNDRR Terminology Translations into Kono, Krio, Limba, Mende, Themne. London: University College London.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. London and New York: Fontana Press, 1993.

Hvistendahl, Mara. 2017. “Reiche Welt – Arme Welt.” Spektrum der Wissenschaft 3 (2017). Special issue: Die Zukunft der Menschheit: 78-85.

IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2018. World Disasters Report: Leaving No One Behind. Geneva: IFRC.

Koselleck, Reinhart. 2006. Begriffsgeschichten. Studien zur Semantik und Pragmatik der politischen und sozialen Sprache. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Luhmann, Niklas. 1971. “Sinn als Grundbegriff der Soziologie.” In Theorie der Gesellschaft oder Sozialtechnologie, edited by Jürgen Habermas and Niklas Luhmann, 25-100. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Luhmann, Niklas. 1995. “Was ist Kommunikation?” In Soziologische Aufklärung 6. Die Soziologie und der Mensch, 84-111. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Macarthy, Joseph M., and Mary S. Kamara. 2021. “Fire Disaster Makes More than 1,000 Homeless in Freetown.” International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). Accessed August 22, 2025.

Milev, Yana. 2001. Emergency Design. Berlin: Merve.

Musoke, Robert, Alexander Chimbaru, Amara Jambai, Charles Njuguna, Janet Kayita, James Bunn, Anderson Latt, Michel Yao, Zabulon Yoti, Ali Yahaya, Jane Githuku, Immaculate Nabukenya, Jane Maina, Stanley Ifeanyi, and Ibrahima Socé Fall. 2020. “A Public Health Response to a Mudslide in Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2017: Lessons Learnt.” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 14 (2): 256–264.

OCHA (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs). 2004. Glossary of Humanitarian Terms in Relation to the Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict. Policy Development and Studies Branch. New York: United Nations. First published 2003. Accessed August 30, 2025.

Oliver-Smith, Anthony. 1999. “What Is a Disaster?” In The Angry Earth: Disaster in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Anthony Oliver-Smith and Susanna M. Hoffman, 18-34. New York: Routledge.

Pickering, Shaun, Chloe Franklin, Jonas Knauerhase, Pious Mannah and Federico M. Federici. 2023. “Multilingual Crisis Communication, Language Access, and Linguistic Rights in Sierra Leone.” In The Routledge Handbook of Translation, Interpreting and Crisis, edited by Christophe Declercq and Koen Kerremans, 221-235. London: Routledge.

Richards, Paul. 2016. Ebola: How a People’s Science Helped End an Epidemic. London: Zed Books.

Rogers, Everett M. 1962. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press, 2003.

Sommer, Bernd, and Harald Welzer. 2014. Transformationsdesign. Wege in eine zukunftsfähige Moderne. München: Oekom.

Schulz, Jürgen. 2021. Krisenkommunikation. Berlin: Wissenschaftsverlag.

Schulz, Jürgen. 2021. “Risiko, Krise und der Sinn von Kommunikation.” Transfer – Zeitschrift für Kommunikation und Markenmanagement 67 (1): 20-25.

Schulz, Jürgen. 2022. Glossar der Sicherheitsgesellschaft: Gegen die Verlockung der Eindeutigkeit. Berlin: Edition Ästhetik & Kommunikation.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, 271-313. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

UN (United Nations). 2015. “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” A/RES/70/1. New York: United Nations General Assembly. Accessed August 30, 2025. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

UCL (University College London – Centre for Translation Studies). 2021. Disaster Risk Reduction Terminology. London: UCL. In collaboration with UNDRR – United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Accessed August 22, 2025.

UNDRR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction). 2017. “UNDRR Terminology.” Accessed August 22, 2025. https://undrr.org/terminology.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction – predecessor of UNDRR). 2015. “Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030.” Accessed August 22, 2025.