Deep Time

Siegfried Zielinski

At the turn of the last millennium, the Italian Semiologist and writer Umberto Eco had a conversation (planned for publication) with the palaeontologist and biologist Stephen Jay Gould, who was at the time still teaching at Harvard and whose book Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle: Myth and Metaphor in the Discovery of Geological Time (1987) had provided an excellent template for the dialogue. The subject of the conversation is nothing less than time, or more precisely, the end of time. The two universally educated, exceptional thinkers stand for the Christian-Jewish cultural heritage, the essence of which has also characterised Western science and its epistemologies. Gould identifies Christianity as the inventor of an all too narrowly defined time for the age of planet Earth. With the concept of the birth of the incarnate Son of God into the reality of the Earth, Christian theologians saw the need to precisely locate this event in time within a fixed framework. Determining a beginning and an end of the natural world accessible to us is a necessary consequence of the biblical concept. After many attempts at definition before him, the Irish archbishop and Anglican theologian James Ussher (1581-1656) set the age of the Earth in the 17th century at around 6,000 years, which is an arbitrary determination. For each day of creation, he envisaged 1,000 years of life for the planet that had temporarily granted hospitality to humans. (The seventh day is dedicated to rest and contemplation.) Everything that exists and has happened in terms of observed events must fit into this stable time corset. Ussher dates the time of creation as 23 October 4004 BC.[i] This means that Eco and Gould have outlived the prophesied age of the Earth and are already beyond the end of time.

Concepts of mechanics tend towards determinism. Isaac Newton’s mechanical cosmology, as a perfect clockwork, was still based on the narrow limits of the Christian determination of time. It was not until the Enlightenment that the metaphysically determined geophysical edifice of the Occident began to totter. Almost every more scientifically advanced European country had one or more protagonists in this era who, as the French natural scientist Georges Louis Le Clerc de Buffon put it in his grandiose work Les Epoques de la nature (1778), “tampered with the narrow definitions by observing real things.”[ii] Based on his empirical observations and calculations, he already assumed an age of the Earth that must have spanned more than 70,000 years.

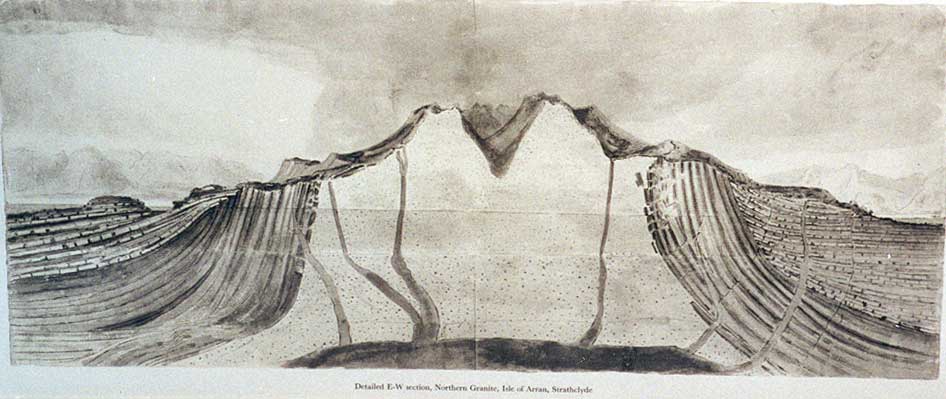

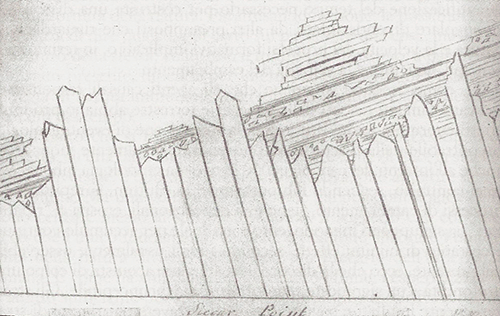

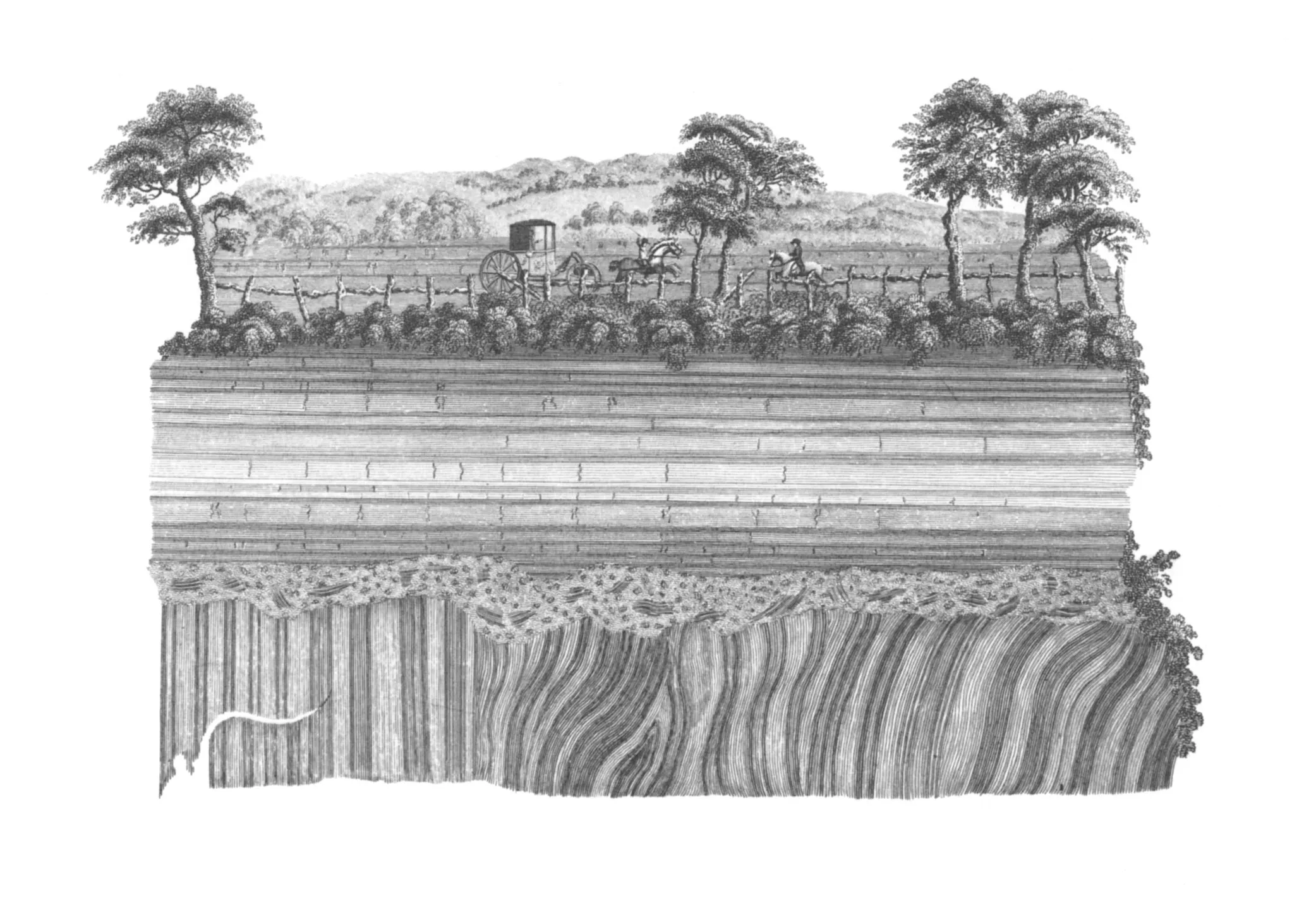

In Great Britain, it is the Scottish mineralogist and chemist by passion, farmer, and philosophical writer James Hutton who radically opens up the perspective for an Earth time that goes far beyond the conventional definitions. During extensive field studies on the coasts of Scotland, above all at Siccar Point, but also in Glen Tilt, on the Isle of Arran or the Isle of Man, he discovers huge strata of black shale and other vertical rock formations between and beneath the extremely hard horizontal basalt layers of the Earth, which had previously been regarded as the final stratification, which must have been hurled upwards over a long period from the hot depths of the Earth by the water masses of the open sea, cooled and solidified in a vertical expansion.

In 1785, Hutton published the theoretical conclusions of his observations on the “System Earth” in a report for the physics section of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, which he had founded (Hutton 1785). Three years later, he expanded his report into an already quite extensive “Theory of the Earth” (Hutton 1788). This Tractatus then essentially constitutes the content of the first chapter of the first two volumes of his Theory of the Earth, published in 1795.[iii] Hutton was unable to complete the third volume, however, as he died two years later. It took another 100 years before it was published in Great Britain (1899). Volume III is of particular importance in that it contains the eminently descriptive and precise engravings by Hutton’s friend, John Clerk of Eldin, some of which have become iconic for geophysical research.[iv] Indeed, I would argue that it is above all the impressive illustrations that have made Hutton’s findings accessible to a somewhat wider readership and given them visual coherence and discursive mobility in the sense of Latour’s “immutable mobiles” (Latour 1990). The natural scientist senses that the new epistemes to which he is trying to create access are not understood by many. At the end of the second volume of his Theory of the Earth, he writes: “... the evidence of those truths is not open to a vulgar view; media are required, or much reasoning.” (Hutton 1795, vol. 2, 539, 549).

The first two volumes of Theory of the Earth run to almost 1,200 pages. The scientific prose that Hutton has written is rather ponderous, sometimes clumsy, often rambling and meandering – one reason why his works on the theory of the Earth, but also his treatises on the theory of rain (Hutton 1788), on general natural philosophy (Hutton 1792), or the philosophy of light, heat and fire (Hutton 1794) have remained little known. However, he concludes the first chapter of The Theory of the Earth with a clear summary, the final formulations of which have revolutionised geophysical research in the long term: “For having, in the natural history of this earth, seen a succession of worlds, we may from this conclude that there is a system in nature ... by which they are intended to continue these revolutions. But if the succession of worlds is established in the system of nature, it is in vain to look for anything higher in the origin of the earth. The result, therefore, of our present enquiry is that we find no vestige of a beginning, – no prospect of an end.” (Hutton 1795, vol. 1, 200; emphases SZ)

With the last sentence, Hutton does not want to confirm the natural philosophical concept of eternity as handed down by Aristotle. Epistemologically, he repeatedly emphasises in his text that he cannot recognise things directly, not really, but only counts what he knows how to formulate as thoughts about things (Hutton 1795, vol. 1, 187); for him, of course, based on the data and facts that are available to him or that he works out for himself. Hutton’s concept of time can be seen as fundamentally ambiguous. The decisive factor for him is the openness of the system, which he analyses using the example of the part of the world inhabitable by humans. He generalises what he specifically observed in 1788 on a rocky outcrop near Siccar Point, which made him a blasphemous thinker for many, and which will make him the protagonist of the enlightened science of a new “Earth Sciences” in the eyes of others: The Earth is not only much older than previously assumed by Christian doctrine. It is so immeasurably old that the tumblings who temporarily inhabit it can hardly imagine its actual temporal extent.

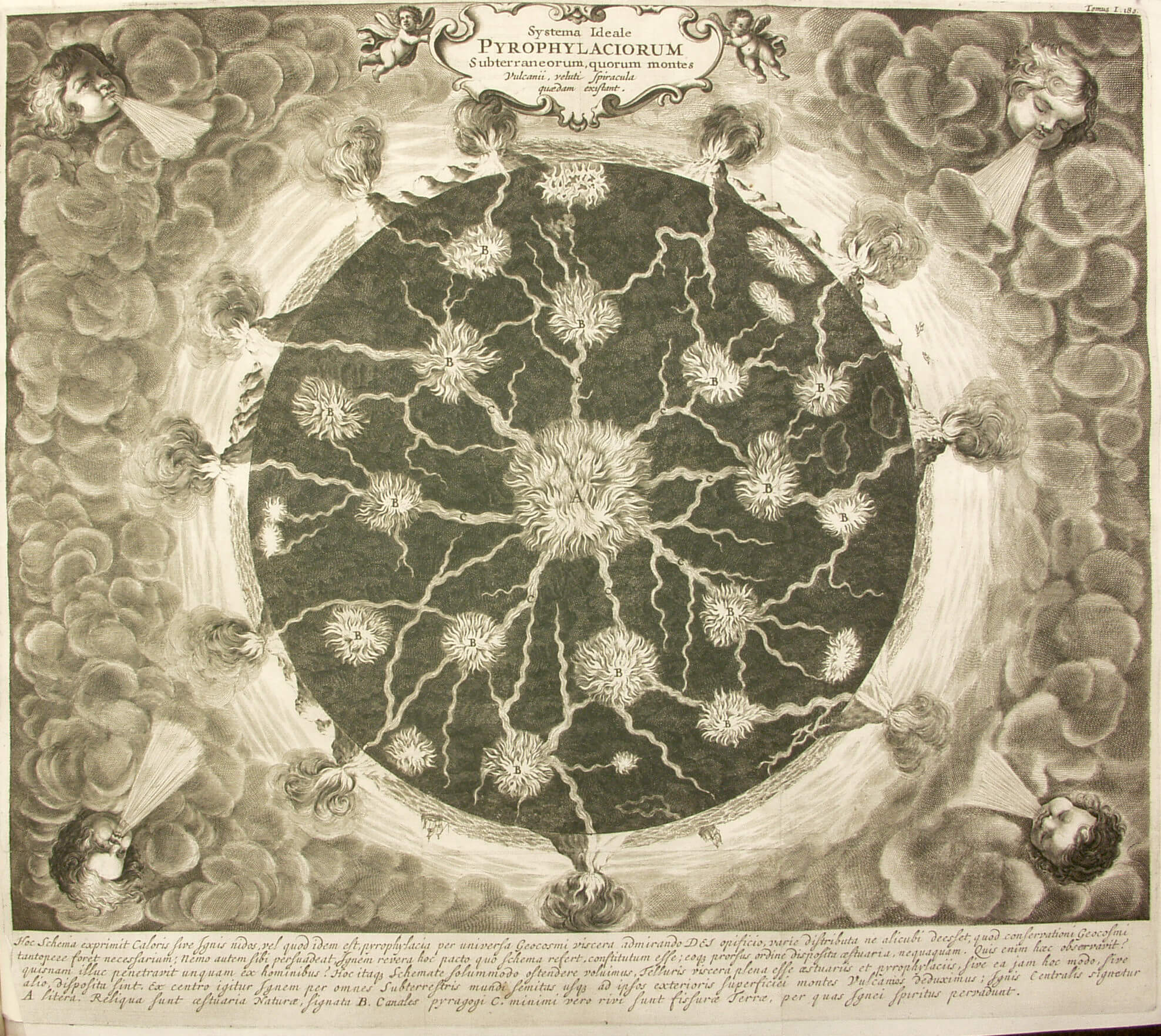

For Hutton, the system that he aims at as a hermeneutic explanation for the human habitat is dynamic in principle. The Earth is constantly changing in its material form. Fuelled by the immense heat deep inside the Earth, rock masses liquefy, erupt onto the surface of the oceans, solidify into hard masses, disintegrate again and become the starting material for the next formations. The evolutionary model that Hutton follows has a cyclical character. In it, movement becomes the basic condition of everything that exists. (Spatial) Structures such as mountains or rocky coasts are therefore only “slowed down time captured by an attractor”, as the biologist, chaos theorist, and time researcher Friedrich Cramer writes in his essay “Duration and Kairos” (Hensel, Reck and Zielinski 2002, 20). Hutton summarises: “Now we have shown that subterraneous fire and heat had been employed in the consolidation of our earth, and in the erection of that consolidated body into the place of land.” And a few paragraphs earlier: “This earth, which is now dry land, was underwater, and was formed in the sea.” (Hutton 1795, vol. 2, 555, 549)

On the one hand, we are familiar with such ideas from ancient European natural philosophy. Anaximander from Miletus was probably the first to develop a decidedly cyclical concept of the history of the Earth in the 6th century BC. Cramer freely translates a fragment of Anaximander’s surviving text (from the perspective of chaos theory): “Beginning and end belong together, the thing cannot forget its origin and returns to it in a cyclical movement, in other words: everything revolves, is coupled back, is reversible.” (Cramer 1996, 17) Aristotle argues in his Metaphysics II: “There are as many kinds of movement and change as there are kinds of being. But since everything in every species is divided according to potentiality and actuality, I call the actuality of the potential, insofar as it is such, movement... Thus, movement is nothing other than the actuality of the potentially existing....” German philosopher Ernst Bloch thus quotes the great Greek philosopher, who was concerned with the fluid boundaries between the Occident and the Orient. For Bloch, Aristotle forms the bridge to the Persian physician, natural scientist, and polymath Ibn Sina (known in Latin as Avicenna, ca. 980–1037), whom he celebrates in an impressive study as an early materiological thinker (Bloch 1952, cited 81). He also originated the idea of a fiery matter in the Earth’s interior that powerfully energises everything that exists on the surface of the planet.[v] Ibn Sina’s book Kitab Al-Shifa (The Book of Healing) is not only the work of a dedicated physician but also a comprehensive encyclopaedia of natural philosophical knowledge. For him, two sets of causes are decisive for the formation of large masses of rock that we classify as mountains or mountain ranges: “The formation of stones in abundance is either at once due to intense heat (probably referring to arid climate) over vast mud area, or little by little through a sequence of days. ...most probably from agglutinative clay which slowly dried and petrified during ages of which we have no record. It seems likely that this habitable world was, in former days, uninhabitable and, indeed, submerged beneath the sea. Then, becoming exposed little by little, it petrified in the course of ages the limits of which history has not preserved; or it may have petrified beneath the waters because of intense heat confined under the sea.”[vi] Important assumptions of Hutton, such as the continuous transformation of the Earth’s body and the paradigm of uniformity, the principle of actuality[vii] in geology, are already present in Ibn Sina’s work, but above all the hypothesis of very long periods that have produced the Earth in its current structure. Empirically, the Persian polymath carried out his geological investigations in the mountains on the border between Uzbekistan and Afghanistan.

The fact that the Scottish naturalist and farmer uses the concept of the machine to characterise what he has observed is nothing unusual for the late Age of Enlightenment. Isaac Newton conceptualised the entire cosmos as a gigantic, moving mechanical universe and thus declared the world inhabited by humans to be a reversible globe. Throughout the 18th century, the construction of self-moving automata that simulated human activities, for example, flourished in Europe. However, the machinic model, which primarily fascinates Hutton and which he references, is that of the steam engine. Thomas Newcomen (1712), Jacob Leupold (1720), James Watt (1769), and John Wilkinson (1777), among others,[viii] developed milestones of the hydraulic-pneumatic energy transformer and all-mover in the 18th century – at the same time as the new scientific concepts of planet Earth were being revolutionised, so to speak. Hutton was very familiar with these developments and adapted them for his research.

However, the idea of the globe as a machine is not enough for the Scottish natural philosopher, especially when it comes to the deep time perspective. Machines are finite because their parts cannot function forever. In the first chapter of his Theory of the Earth (1795), he asks right at the beginning: “But is this world to be considered thus merely as a machine, to last no longer than its parts retain their present position, their proper forms and qualities? Or may it not also be considered as an organised body? … such as has a constitution in which the necessary decay of the machine is naturally repaired, in the exertion of those productive powers by which it had been formed.” (Hutton 1795, vol. 1, 16; emphasis SZ) Hutton stresses that he sets down his investigations in writing in this spirit. He needs the machine as a concept to be able to explain the Earth system (Hutton likes to use the word “globe”), and he needs the “reproductive operation” of the organism because he sees it as ensuring the permanent repair of the machine. If this strong “reproductive power” does not exist, we must assume “that the system of this earth has either been intentionally made imperfect or has not been the work of infinite power and wisdom” (Hutton 1795, vol. I, 17) – as Christianity ascribes it to the almighty Creator, we may imaginarily add. Hutton does not make this idea explicit, but it constantly resonates in his deistic geo-theory (Rudwick 2005, 159). If he were religious at all, then his complex structure of thought follows the basic assumption that only reasonable statements can serve to substantiate theological truths, not speculation.

With his dual understanding of the Earth as a machine and as an organism, he gives the habitable part of the planet the dynamic openness into the future that Newton’s concept of time lacks. A world that is conceived as reversible in the sense of permanent self-preservation wears itself out, becomes emaciated and is available to man as an object of exploitation. The living organism harbours the qualities of surprise, of the not exclusively predictable, of leaping, of renewal. As a researcher, one must be very careful with such historicizations, but James Hutton sensed early on that the habitat should not be left to the machine alone. As a professional farmer, for whom living nature is essential rather than incidental, it is of vital interest to him that nature can always change, possibly to its advantage.

Due to his groundbreaking discoveries in the geophysical world and his radical conclusions, James Hutton is often referred to as the father of modern Earth Science. “The Man Who Found Time” is the equally personalising title of a scientific biography by Jack Repcheck (2003), whereas its subtitle sums up the importance of the Scottish natural scientist well: “James Hutton and the Discovery of the Earth’s Antiquity.” As a result of this discovery, not only has the age of the Earth increased immensely, but also our temporal conception of non-human pluriversal realities, within which human existence is of negligible importance.

Following Hutton later in the 20th century, scientific authors such as John Angus McPhee, palaeontologists and geologists such as Stephen Jay Gould and James Rudwick have valued and further developed the notion of deep time, especially as a geophysical concept. The idea of “Big History” (exemplary: Christian 2004), which attempts to think of human and non-human developments together as an integrated concept, is inconceivable without the idea of a deep time of the Earth and the pluriverse. Historians and philosophers of science have long since discovered the usefulness of the concept for their complex subject areas (also exemplary: Currie 2019). Within media research, its transgressive power has considerably expanded the media archaeology that has been developing for several decades.[ix]

However, the setting of the deep time of the Earth also contains significant ethical and, therefore, geopolitical dimensions. This is what makes the concept so strong and fruitful in the current discussion about possible futures for planet Earth. Deep time means not thinking about history or genealogies (Foucault) deterministically, but conceptualising them as a space of possibility for unfolding processes. The more generously we can grasp the extent of Earth’s existence, the more our responsibility for the planet grows. The less we can concretely imagine, experience, or even precisely measure the consequences of our actions in their spatiotemporal dimensions, the more modest our interventions in the potential equilibrium of heterogeneous natural subjects should be.

Gould, who was also a biologist and historian of science, had already developed this in his writings. When he explains what deep time means from a human perspective, he likes to use a parable borrowed from McPhee’s Basin and Range:[x] “Consider the earth’s history as the old Measure of the English yard, the distance from the king’s nose to the tip of his outstretched hand. One stroke of a nail file on his middle finger erases human history.” What crumbles down, this tiny amount of white dust, would correspond to our meaning within the whole concept of the natural world.

Deep time operates like a seismograph; its activity takes place vertically. Doubts about the linear progress of what we call civilisation are not only justified. It is compellingly confirmed by the daily news of the breathtaking speed at which animal and plant species are disappearing from the Earth and at which the globe is heating up more and more. As a result, the part of the Earth that can be inhabited by humans is not only losing its heterogeneous attractiveness but is simply shrinking as an area worth living in. From James Hutton’s perspective, the current efforts to increase natural diversity, to allow animal and plant species to flourish again or even anew and to at least protect the planet from burning up too quickly through greed and exploitation can also be interpreted as work on the reutilization of the cyclical concept of Earth’s history.

The idea of a deep time of earthly existence can be excellently combined with aesthetic experiences. In recent decades, the Swiss architect and sculptor Peter Zumthor and the Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto are just two of the protagonists who have already made art history in this regard. “From the Depths of Time” is the title of Zumthor’s decidedly tactile book, which is dedicated to inconspicuous everyday objects that were made and shaped with great care a long time ago: an antique door handle, a centuries-old disc pin, a fragment of a bannister, beautifully carved wooden statues... Like no other contemporary architect, Zumthor integrates the very old and the new into a common space of possibility. The Kolumba Diocesan Museum in Cologne is a masterpiece in this respect. He has incorporated archaeological material into the new museum building, including the floor plan of a Gothic church ruin and fragments of an ancient excavation, as can still be found in subterranean Cologne from Roman times.

For me, Sugimoto is the philosopher of time among contemporary artists. Most of his works tell of encounters that take place in the depths of time – outstandingly his “Seascapes” from the 1980s and 1990s, in which open seas and horizons seem to be lost in immeasurable time. He inserted one of these artefacts into an antique Buddha reliquary that looks like a monstrance; the work is called “Time’s Arrow. Seascape” (1987). Or his precise photographs of fossils, in which two preservations of time take place within one another: the one preserved in the prehistoric rock, and the one that becomes visible in the photograph. He calls this artistic storage practice “Pre-Photography Time-Recording Device”.[xi]

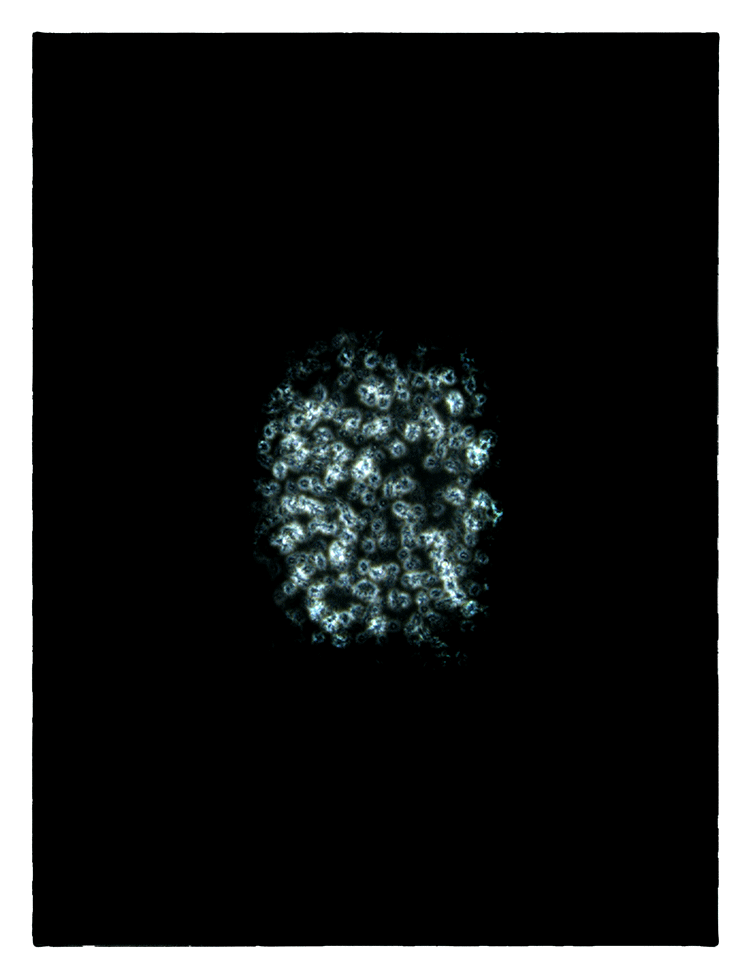

In 2009, Yuan Gong from Shanghai was an artist in residence at the archaeological department of Peking University and became involved in the archaeological excavation of the Zhou temple in Shaanxi Province. In his work complex, the “Duke of Zhou Soil Collection Plan” he presented some of the excavated thousands of years old material as extremely valuable, as objects for the art market. “Forgotten Memories” (2024) is an animation by Wang Yuyang, a creation with copper-red curved limbs and many glowing eyes that could have originated from the depths of the sea, a kind of Vampyroteuthis infernalis[xii]. To allow the sensation-hungry museum visitor to experience through the installation ancient past presences, the artist consumes an extremely valuable natural material that has evolved over hundreds of thousands of years and is currently disappearing from our planet at an insane rate: glacier ice. The machine proves itself to be anti-nature and grounded in nature. On the other hand, the delicate techno-structure with pistons, funnels, and an animalistic appearance makes palaeontological time tangible. Humanoids of the 21st century can breathe in the oxygen released by the ancient ice as the machine at the heart of the installation heats it and turns it back into water. Humans can actively participate in the rapid disappearance of natural resources in the Anthropocene.

In contemporary visual art, artistic activism, and performance, the reactivation of distant cultural, technological, or political experiences using aesthetic and poetic means has almost become a genre in its own right, one that has been heavily explored by women in recent years. With her large-format painting “Inner Life” from 2009, Rosalie Lang seems to want to celebrate Clerk’s drawings for Hutton’s Theory of the Earth in downright opulent colour. Her painting is an important part of the 2014 exhibition “Imagining Deep Time” at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC. Fifteen different artists are presenting their aesthetic ideas here. “Weaving the Inner Bark” is an ambitious project developed by the international curatorial ensemble Leila Bencharnia, Chiara Figone, Miriam Gatt, Samira Ghoualmia, Paz Guevara, Beya Othmani, Savanna Morgan and Salma Kossemtini for ARCHIVE Berlin 2023. The project focuses on the textile weaving practices of women whose knowledge and skills date back many centuries. In “Khipu: Pre-Hispanic Electrotextile Computer” (2024), Constanza Piña Pardo takes a quantum physics perspective on the ancient computing system from the pre-Columbian Andean cultures, which has already been reconstructed in several artistic research projects (including by the Spaniard Lorenzo Sandoval and the Colombian Gabriel Vanegas). In this calculation system, discrete numerical information is knotted together using strings and thus coded. The young Indonesian media artist Natasha Tontey is passionate about the knowledge and technical practices of her ancestors. In the project “Makatana” (2022/23), she uses artistic means to examine ancient technologies, healing practices and the machine philosophy of Minahasa cosmology in her homeland in the north of the Indonesian region of Sulawesi.

Finally, I would like to focus on an artist who works explicitly and offensively with the concept of deep time (Fecht 2019).[xiii] In his series of works titled “Incertitudes” (2016), the artist Tom Fecht seems to want to give us a glimpse into the infinity of the macrocosm with its countless points of light in lost blackness. In material terms, however, we are dealing with a microcosmic techno-aesthetic sensation. For many hours, the artist has exposed a large-format photographic negative to sheets of old silver gelatine film. What we can see on the technical artefacts, which are over two metres wide, are the silver crystals of various sizes, numbering up to a million, which appear to have been catapulted out of a deep black background. To play once again with Gould’s/McPhee’s parable: the photon dust of the stars falling from the cosmos, the immeasurable number of light particles that have inscribed themselves on the negative of the photographs after hours of labour, come from a time in the past that we can at best calculate only in aspects and think with our imagination. This also applies to Fecht’s more recent series of works, “Studies of Ancient Light” (2021). In its true depth, the chronological time that we can experience always points beyond itself and us. It tends towards a duration that far exceeds our earthly existence, which we therefore cannot experience.

We find such thoughts already impressively formulated in the ancient natural philosophy of China, more precisely in the seventh opening of the founding scripture of Daoism, the Dao de Jing, which was probably written by Lǎo Zǐ (Lao Tzu) in the sixth century BC: “Heaven exists permanently, / the earth is unchanging. / That heaven and earth exist permanently and unchangingly / follows from the fact that they are not created for their own sake; / therefore their creation is eternal. / For this reason, he who is in harmony puts his self aside....”[xiv] Modesty, the luxury of being able to experience the depth of time with our senses, in a way brings us to our knees in front of that which is far greater in its temporal vastness and which we can therefore never really comprehend, even if we would learn to calculate it. Particularly since the machines we use in the 21st century to process data in artificial extelligences consume so much energy that the lifespan of the habitable parts of planet Earth is simultaneously shortened by its increasing digitalisation.

In this sense, deep time is something that I would like to call a dialectical thought thing, following Walter Benjamin’s Denkbilder (thought images), as a tool and a provocation for our idea of habitable nature. It helps us to recognise that the world is much more than we, as tumblings in it, can depict.

References

Al-Rawi, Munim. 2002. “Contribution of Ibn Sina to the development of Earth Sciences.” https://muslimheritage.com/ibn-sina-development-earth-sciences.

Belting, Hans. 2009. Looking through Duchamp’s Door. Art and Perspective in the Work of Duchamp. Sugimoto. Jeff Wall. Cologne: Walther König Publishers.

Bloch, Ernst. 1952. Avicenna und die aristotelische Linke. Berlin: Rütten & Loening.

Buffon, LeClerc de, Georges Louis. 1781. Epochen der Natur, vol. 1. St. Petersburg: Logan.

Christian, David. 2004. Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Craig, Gordon Y., Donald B. McIntyre and Charles D. Waterson. 1978. James Hutton’s Theory of the Earth: The Lost Drawings. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press.

Cramer, Friedrich. 1996. Der Zeitbaum: Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Zeittheorie. Leipzig: Insel.

Currie, Adrian. 2019. Scientific Knowledge and the Deep Past. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eco, Umberto, Stephen Jay Gould, Jean-Claude Carrière and Jean Delumeau. 1999. Conversations about the End of Time. London: Penguin.

Fecht, Tom and Anna Le Moine Gray. 2024. Incertitudes. Pont-Croix: Le Marquisat.

Fecht, Tom. 2019. TiefenZeit/Deep Time. Duisburg: Museum DKM.

Flusser, Vilém and Louis Bec. 2012. Vampyroteuthis Infernalis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gould, Stephen J. 1987. Time’s Arrow and Time’s Cycle: Myth and Metaphor in the Discovery of Geological Time. 3rd ed. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Hensel, Thomas, Hans Ulrich Reck and Siegfried Zielinski (eds.). 2002. Goodbye, Dear Pigeons – Lab: Jahrbuch 2001/02 für Künste und Apparate, for the Academy of Media Arts, Cologne. Cologne: Walther König.

Hutton, James. 1785. Abstract of a Dissertation read in the Royal Society of Edinburgh, upon the seventh of March, and fourth of April, MDCCLXXXXV, concerning the System of the Earth, its Duration, and Stability.

Hutton, James. 1788. The theory of rain. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, vol. 1.

Hutton, James. 1792. Dissertations on different subjects in natural philosophy. London: Strahan & Cadell.

Hutton, James. 1794. A dissertation upon the philosophy of light, heat, and fire. London: Cadell, Jr. and Davies.

Hutton, James. 1795. Theory of the earth with proofs and Illustrations, 3 vols. London: Messrs Cadell, Jr. and Davies; William Creech.

Hutton, James. 1959. Theory of the earth, with proofs and illustrations: In four parts. Reprint. Weinheim/Bergstr.: Engelmann.

Lǎo Zǐ. 2019. Dao de Jing. Transl. Michael Hammers. Munich: Manesse, London: Penguin.

Latour, Bruno. 1990. “Drawing things together.” In: Representation in Scientific Practice, edited by Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Mattschoss, Conrad. 1908. Die Entwicklung der Dampfmaschine: Eine Geschichte der ortsfesten Dampfmaschine und der Lokomobile, der Schiffsmaschine und Lokomotive. Berlin: Julius Springer.

McPhee, John. 1980/1981. Basin and Range. New York: The Noonday Press.

Parrika, Jussi. 2015. A Geology of Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Repcheck, Jack. 2003. The Man Who Found Time: James Hutton and the Discovery of the Earth’s Antiquity. New York: Perseus Publishing.

Rudwick, James. 2005. Bursting the Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zielinski, Siegfried. 2006. Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Zielinski, Siegfried. 2020. “The World as Organism and Machine: Jesuit Geophysics in the Early Modern Era.” In Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth, edited by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, Karlsruhe: ZKM Karlsruhe.

Notes

[i] In the first part of the conversation, Gould talks about the complicated calendar calculations that various representatives of Christianity have made in detail (see Eco et al. 1999, ca. 4–18).

[ii] Quoted here from the German translation (Buffon 1781, 7).

[iii] Hutton 1795, reprinted 1959 by Engelmann, Weinheim/Bergstr. This edition also contains the engraving by Clerk.

[iv] Republished as James Hutton's Theory of the Earth: The Lost Drawings (Craig, Mc Intyre and Waterson 1978).

[v] For Bruno Latour’s, Peter Weibel’s, Martin Guinard’s, and Bettina Korintenberg’s exhibition project on "Critical Zones", I have discussed in this context the heuristics of Athanasius Kircher, who in his two-volume treatise on the Earth, Mundus Subterraneus (1665), attempts to describe the fiery and energetic interior of the Earth grandiosely like a world machine (cf. Zielinski 2020). Kircher equated mineral and biological growth; they were both energised by the central fire. The electronic music group Lightwave dedicated an entire musical album to the acoustic staging of Mundus Subterraneus in 1995.

[vi] A clear presentation of Ibn Sina’s relevant findings and their sources can be found on the website “Muslim Heritage,” which is run by the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation based in London (Al-Rawi 2002).

[vii] In his writings, Hutton assumes that events in the physical world that took place in the depths of time can be deduced from the evidence found in current rock formations.

[viii] For the history of the steam engine, see the monumental work by Conrad Mattschoss (1908; here volume 1).

[ix] In addition to my own work on “Deep Time of the Media” (Zielinski 2006 [2002]), see Parrika 2015.

[x] McPhee (1980/1981) devotes great attention to Hutton in the chapter “Angular Unconformity” of his book Basin and Range. Gould (1987) tells the story in his own way in the chapter entitled “Deep Time” in his Time’s Arrow and Time’s Cycle: Myth and Metaphor in the Discovery of Geological Time.

[xi] On this work, but also on Sugimoto’s photographed wax figures, see Belting 2009, 77–135.

[xii] This is the title character of a fantastic, early posthumanism book by Vilém Flusser and Louis Bec (English edition 2012).

[xiii] On the project “Incertitudes”, see the book of the same name, which Fecht wrote with Anna Le Moine Gray (2024).

[xiv] Quoted from the new translation from the Ancient Chinese into German by Michael Hammers (Lǎo Zǐ 2019, 59; English transl. SZ). Generously, the date of origin of the Chinese original, whose definitive authorship is still debated, is dated between -770 and -476.