Curating Water

Celina Jeffery

Related terms: becoming-witness, curatorial ethics, critical ocean studies, decolonial curating, feminist care ethics, Indigenous sovereignty, more-than-human, relational, reparative aesthetics, water.

Contemporary art exhibitions increasingly serve as sites where ecological crises are represented. However, they remain understudied as spaces of climate knowledge production. To ‘curate water’ in this context entails assembling and presenting artistic works that engage with water’s material, symbolic, and political dimensions. This curatorial approach carries significant ethical responsibilities. It must navigate colonial histories of water use, foreground Indigenous knowledge of waterways, and embrace feminist and more-than-human perspectives that recognize water and nonhuman life as active agents rather than passive resources. Contemporary curatorial practice is thus being reimagined through the lens of environmental humanities, expanding the curator’s role from caretaker of objects to caretaker of relationships within a more-than-human world.

The word ‘curator’ derives from the Latin cūrā (‘care’) and cūrāre (‘to care for’), and in museological practice it has come to signify the selection, organization, and stewardship of objects within a collection or exhibition (Cresswell 2021). Traditionally, to ‘curate’ meant to care for artworks or artifacts, a duty historically embedded in anthropocentric displays oriented toward spectators in colonial contexts (Bennett 1995). While curatorial work often remains entangled in colonial and anthropocentric museological frameworks, privileging relationships among artists, audiences, and institutions, an emergent shift seeks to decenter such paradigms by engaging water not merely as a subject but as a collaborator, witness, and co-agent of meaning. Curator Stefanie Hessler draws on Kamau Braithwaite’s concept of “tidalectics” to consider water’s transitory and temporal rhythms, which unsettle the fixity of place and linear narratives. This dynamic interplay stirs together pasts and futures in a continual back-and-forth that challenges dominant boundary frameworks of place, time, and agency (Hessler 2018). Within the context of environmental crises, such curatorial ethics expand to recognize relationality among more-than-human ‘participants’ -rivers, oceans, lands, and the lifeforms that depend on them, alongside the frameworks in which they are represented and entangled.

Instead of engaging with water ecologies through the traditional Western Romantic framework, characterized by extractivism, the sublime, the masculinist gaze, and colonial aesthetics, this approach promotes a relational practice of “thinking with water” grounded in reparative care (Neimanis 2013; Puig de la Bellacasa 2017). By engaging water, its histories, and its entanglement with other nonhuman entities as active partners in the curatorial process, curating becomes a form of environmental humanities scholarship: a mode of inquiry and storytelling that bridges artistic practice with ecological knowledge and cultural critique. In this expanded framework, exhibitions are positioned as sites of interdisciplinary convergence, where scientific, Indigenous, and artistic ways of knowing the environment intersect and generate new epistemological and ethical insights.

This reimagined curatorial model aligns closely with insights from the blue humanities and critical oceanic studies. Here, Elizabeth M. DeLoughrey foregrounds postcolonial hydro-logics and more-than-human ontologies to reconfigure the ocean as archive, actor, and agent of planetary interconnection (DeLoughrey 2019). The 2025 exhibition Can the Sea Save Us? at the Sainsbury Centre exemplifies this approach. It staged three interlinked exhibitions - A World of Water, The Sea Inside, and Darwin in Paradise Camp: Yuki Kihara - each drawing on DeLoughrey’s call to understand the ocean across historical, cultural, and ecological registers. The exhibition’s titular question, Can the Sea Save Us?, encapsulates a central tension: how might we envision the ocean as a potential site of planetary preservation, while also acknowledging the urgent need to save the sea itself from the compounded effects of human pollution, climate change, and the sedimented legacies of colonial and capitalist extractivism (Moore and Paranada 2025)? In A World of Water, curated by John Kenneth Paranada, the accelerating erosion of East Anglia’s coastlines is brought into conversation with the Netherlands’ long-standing histories of hydraulic engineering and inundation through immersive and transhistorical artworks. The second exhibition, The Sea Inside, curated by Pandora Syperek and Sarah Wade, turns inward to explore affective and immersive relationships between human and more-than-human ocean worlds in contemporary art, investigating the role of psychological encounters, myth, and the mundane (Syperek and Wade 2025). Here, water is framed not only as a climate actor but also as a site of kinship, intimacy, and multispecies interrelation. The third component, Darwin in Paradise Camp: Yuki Kihara, curated by Tania Moore, centers fa‘afafine and queer Pacific perspectives to reimagine the colonial legacies of Paul Gauguin and Charles Darwin. Kihara, a Japanese-Sāmoan fa‘afafine artist, critiques dominant evolutionary and gender narratives while addressing rising seas and possibilities of queer oceanic kinship. At the heart of Can the Sea Save Us? lies a decolonial curatorial logic that engages colonial histories and hydro-colonial narratives through poetic and political acts of bearing witness. Rather than relying on spectacle or tropes of disaster, these exhibitions foreground local creative knowledge and lived experience, attuned to deep time and planetary tipping points, as well as deeply subjective, speculative, and even uncanny modes of engagement.

As artistic strategies shift to addressing localized sea-level rise, inundation, and the “slow violence” of disappearing islands (Nixon 2011), the conceptual challenge transforms from evoking grandeur to grappling with vulnerability, precarity, and loss, often with an ethics of care aligned with both decolonial and feminist curating. The exhibition Inundation: Art and Climate Change in the Pacific, curated by Jaimey Hamilton-Faris at the University of Hawaii’s Manoa Art Gallery, considered this relationship between art, sea level rise, and climate change, focusing on the Pacific Islands (Hamilton-Faris 2020). Faris-Hamilton’s curatorial framework uses ‘inundation’ as a fluid and evolving set of aesthetic considerations – a means of articulating impermanence, shifting geopolitical and natural boundaries, and the immersive or non-narrative potentials of inundation through specific and localized, Indigenous cultural and mythological references. Here, the curator’s role is also reparative in nature, positioning the exhibition as a site of ethical engagement by relating the environmental justice issues of rising seas to Indigenous sovereignty. María Puig de la Bellacasa’s “thinking with care” helps articulate this ethos, urging recognition of complex, vulnerable relationships among human and non-human entities, and positioning curatorial work as relational practice (Bellacasa 2017). To ‘curate water’ in this regard is to repair – to gather fragmented and submerged realities and reassemble them into new constellations of meaning. This reparative impulse echoes Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s notion of the “reparative reading,” which accepts the world’s brokenness while imaginatively forging connective and sustaining possibilities (Sedgwick 2003).

Inuvialuk artist Maureen Gruben works with these reparative gestures in Stitching My Landscape (2017), where she threads bright red cloth through melting ice, physically and symbolically suturing the terrain of her home, the hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk, which is being breached by climate change (Hodgins 2023). Rather than invoking the metaphor of the floe – dispersal and drift – Gruben turns to the suture, a method of mending. Curated by Tania Willard for the Canadian Landmarks initiative, the work foregrounds care as a performative and embodied act, less about charting disintegration than about insisting on continuance, relational sovereignty, and intergenerational responsibility at the ice edge. Willard’s curation of Gruben’s Stitching My Landscape, staged on the ice, is an instance of how curators might reckon with the museum’s own carbon and colonial legacy, in part by inviting audiences to be attentive to the relational ethics between Indigenous survival and presence.

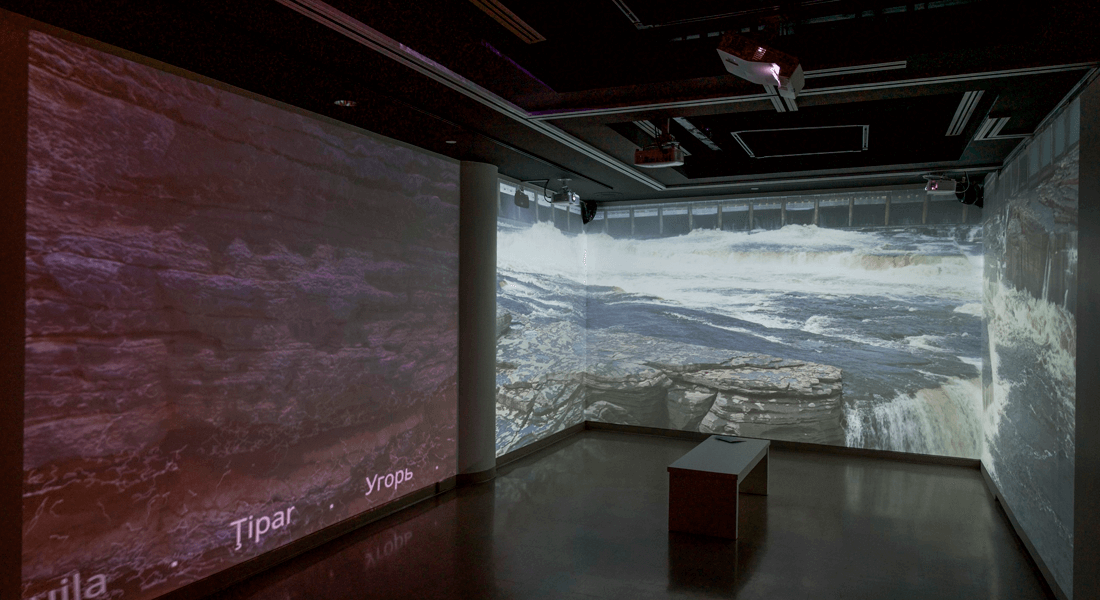

Water entangles and invites us to consider how it holds the world – both materially and metaphysically. As Leanne Betasamosake Simpson writes, travelling by water carries the memory of ancestors: the canoe becomes a vessel of alignment, offering a relational vantage point that lets us view the shore as a space of continuous “interconnected worlds,” of edges, zones, and areas of intensive transition (Simpson 2024). In my exhibition Entanglements (2022-3), Cree artist Cheryl L’Hirondelle explores kinship with eels in the Ottawa River through the immersive media installation nipawiwin Akikodjiwan: Pimizi ohci (figure 1). The artist draws on the Cree worldview nêhiyawin, inviting the audience to imagine multispecies kinship in our watery world (Jeffery and Stec 2022). Immersed in three-wall projections of the rushing Akikodjiwan/Chaudière Falls, L’Hirondelle’s installation highlights the endangered American eel’s arrival after an epic migration from the Sargasso Sea to this hydropower-obstructed river juncture. The work includes the naming of eels in over 100 languages, emphasizing their cultural significance across diverse communities. It implicates turbines, pollution, climate change, and trafficking as forces imperiling elvers struggling upstream, while inviting viewers into a kinship-forming, underwater vantage that echoes the eel’s decades-long life cycle before its return oceanward to spawn and die. This multispecies engagement resonates with Deborah Bird Rose and Thom van Dooren’s concept of “becoming-witness,” an ethical attentiveness to the lives, deaths, and suffering of more-than-human beings in the Anthropocene (Rose and van Dooren 2015). Drawing on Karen Barad’s notion of “intra-action,” they argue for a relational ethics rooted in openness, curiosity, and care (Barad 2007). As they write, “we are called not to abandon others and, more positively, we are called to engage others in the meaningfulness of their lives” (Rose and van Dooren 2015, 125). ‘Becoming-witness’ involves standing as witness and actively bearing witness – a mutual, life-affirming practice that resists social death and instead insists on expansive recognition and responsibility. In curatorial terms, it offers tools for reimagining exhibitions as spaces of multispecies grief, ecological solidarity, and care.

Taken together, these examples and insights invite a rethinking of curatorial practice as a relational engagement that transcends traditional human-centered frameworks. This entry draws on this understanding to frame ‘curating water’ as an ongoing dialogue with its fluid multiplicity, deliberately challenging anthropocentric perspectives by positioning humans and nonhumans as collaborative partners. As Stefan Helmreich emphasizes in A Book of Waves, ocean waves “must be read as things material and formal, concrete and conceptual” (Helmreich 2023, 26). He describes waves as forces of agitation and intermixture, constantly churning, and as media whose meaning intertwines the historical legacies and future possibilities of the ocean. To think like a wave is to embrace complexity, unpredictability, and the continual breaking and reforming of boundaries. Curating water thus becomes an act of attuning to these rhythms, navigating the churn between past and future, human and nonhuman, form and flux, and creating exhibitions that resonate with water as a dynamic and historically charged agent where ecological, political, and temporal forces intermingle and unfold.

Figure 1. Cheryl L’Hirondelle, nipawiwin Akikodjiwan: Pimizi ohci. 2022. Media Installation at Karsh Masson Gallery. Photo by David Barber. Image courtesy of the artist and the Entanglements exhibition.

References

Bennett, Tony. 1995. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge.

Barad, Karen, 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Cresswell, Julia. 2021. “Curate” In Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins, 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 2019. Allegories of the Anthropocene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Gruben, Maureen. 2017. “Stitching My Landscape.” Accessed June 1, 2021. https://www.maureengruben.com/stitching-my-landscape.

Hamilton-Faris, Jaimey. 2020. Inundation. https://www.inundation.org. Accessed July 2, 2021.

Helmreich, Stefan. 2023. A Book of Waves. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hessler, Stefanie (Ed.). 2018. Tidalectics: Imagining an Oceanic Worldview through Art and Science. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Hodgins, Laura. 2023. “The Answer Is Land.” In Boundless North: Art Across Borders, Inuit Art Quarterly (Summer).

Jeffery, Celina, and ArtEngine, curators. 2022. Entanglements. Featuring Cheryl L’Hirondelle, Meryl McMaster, Sasha Phipps, and The Macronauts. Karsh-Masson Gallery, Ottawa, Canada. November 17, 2022 – January 13, 2023.

Neimanis, Astrida. 2013. “Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water.” In Thinking with Water, edited by Cecilia Chen, Janine MacLeod, and Astrida Neimanis, 85–122. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Moora, Tania, and John Kenneth Paranada, eds. 2025. Can the Sea Save Us? Norwich: Sainsbury Centre/Kulturalis Ltd.

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Rose, Deborah Bird, and Thom van Dooren. 2015. “Encountering a More-than-Human World: Ethos and the Arts of Witness.” In Manifesto for Living in the Anthropocene, edited by Katherine Gibson, Deborah Bird Rose, and Ruth Fincher, 120–128. Canberra: ANU Press. https://doi.org/10.22459/MLA.01.2015.12.

Sainsbury Centre. Can the Sea Save Us? March 15–October 26, 2025.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. 2003. “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading; or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You.” In Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, 123–151. Durham: Duke University Press.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. 2025. Theory of Water: Nishnaabe Maps to the Times Ahead. Toronto: Alchemy / Penguin Random House Canada.

Syperek, Pandora, and Sarah Wade. 2025. “Sea Inside: Art and Marine Interiority.” In Can the Sea Save Us? Norwich: Sainsbury Centre/Kulturalis Ltd.