Coast

M. J. Jessen and S. Bisgaard

Related terms: amphibious, beach, ecotone, edge, line, liminal, littoral zone, shore, transition, zone

The coast is dynamic, sudden, overwhelming, rhythmic, and quiet. The coast is a meeting with deep time, with ideas of the sublime, with fear, and with longing. It is a physical transition between wetness and dryness. A meeting of elements and ecosystems, of trade and mythologies, of conquest and of calm. A World Picture (Lund & Carstensen 2023). In the following, we wiggle our way through a stream of coastal considerations, like an eel on its way to the Sargasso Sea.

Marine biologist Rachel Carson opens The Edge of the Sea poetically:

The edge of the sea is a strange and beautiful place. All through the long history of Earth it has been an area of unrest where waves have broken heavily against the land, where the tides have pressed forward over the continents, receded, then returned. For no two successive days is the shore line precisely the same. Not only do the tides advance and retreat in their eternal rhythms, but the level of the sea itself is never at rest (Carson 1955, 421).

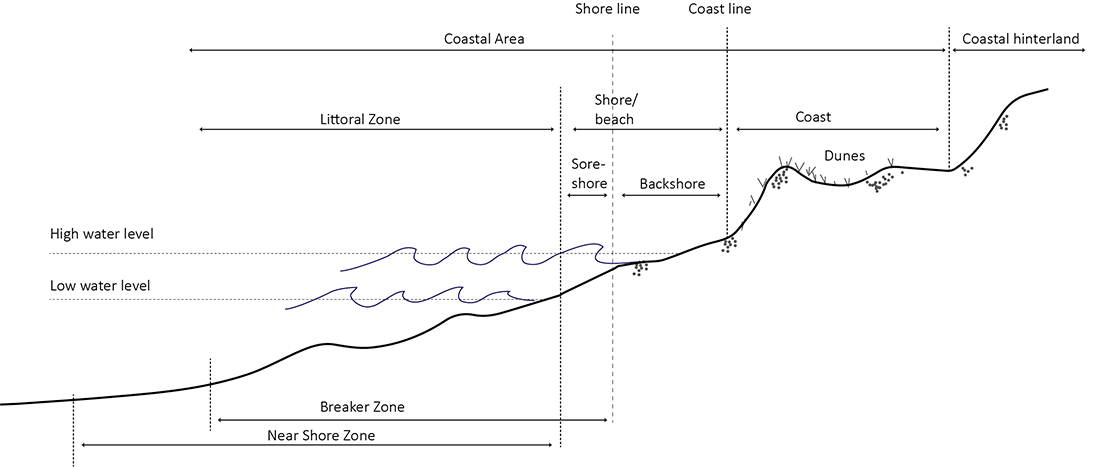

Geologically, the ‘coastal zone’ is a space shaped by the interplay of solid earth, oceanic water, and atmospheric forces, defined as stretching from the offshore point where wave energy begins to affect the seabed to the inland area where the sea no longer exerts morphological, material, or chemical influence (Binderup n.d.; Burcharth & Nielsen n.d.). More generally, it can be defined as a ‘planning-oriented characterisation’ of a 10–100 km wide zone, “delineated as the part of land affected by its proximity to the sea, and the part of the sea affected by its proximity to land” (DHI 2017, 9).

On maps, the coast is often rendered as a line. A coastline. A line that communicates a land-sea division in a measurable and manageable moment. A line from which the sea is on one side, and land is on the other. A line on which the sea is considered sea on one side, and a flood on the other.

This notion of separation is not confined to the coast as coastline but extends to the shore as space. It concerns a liminal space, Margaret Cohen notes, a literary chronotope in which “boundaries are tested, only to be reaffirmed rather than dissolved” (2006, 661). Crossing these boundaries, moving perpendicularly through this space, can make the coast a threshold for yearning.

Aksel Sandemose’s sailor in Ankomst approaches the coast from at sea: “I stood on the deck and felt the seafarer’s old joy, when he sees the coast he is aiming for. The joy hovers over my head, and I bring the holy spirit down with a shot of hail”, taking down a seagull (translated from Sandemose 1953, 84).

Or it can be approached from land, as when Karen Blixen (under the pseudonym Isak Dinesen) lets the young lieutenant Boris in The Monkey exclaim:

There is nothing for which you feel such a great longing as for the sea. The passion of man for the sea [...] is unselfish. He cannot cultivate it; its water he cannot drink; in it he dies. Still, far from the sea, you feel part of your own soul dying, disappearing, like a jellyfish thrown on dry land (1934, 149).

Somewhere, sailing around in a mix of yearnings, is the cruise ship. In Ruben Östlund’s film Triangle of Sadness (2022), it becomes a floating illusion, a fake coastline where the beach is mimicked by chlorinated pools. The sea is something to be looked at, consumed, but never truly entered. The coast becomes a product, not a place to live or connect with. In this grotesque spectacle, the idea of the coast begins to dissolve. There is no longer a clear edge, but the coast is something that can appear anywhere.

In Māori cosmologies, land and sea are not split but form a single continuum. This perspective rejects the premise of the coastline, and thereby the defining claim of the coastline altogether (Sammler 2020). Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha (2020) propose a similar thinking. “‘Wetness is everywhere,’” they write, an all-encompassing wetness reflecting a conception of the world in which there is no such thing as dry, but rather varying degrees of wetness. The sea is very wet, while the desert is less so. “It is the line on the map that makes one see water [as only] somewhere,” they state.

Without maps, lines of sight, from hilltop to headland, have also long served to determine privileges, such as the placement of fishing poles. Standing on hilltops and looking over water. Johanne Pontoppidan Tuxen suggests the land register may have pre-read the Limfjord in north-western Denmark: “When the uppermost of the four hills on Thyrrestrup Mark coincides with the western end of Næsborg Thicket, the chain in Nørl Stream is in legal bearing” (translated from Tuxen 2025).

The coast is long summer evenings, holidays, and sand between toes. A destination. Cliffs and dunes, tidal flats. Windswept and sheltered. Eroding coasts and sediment coasts. Barrier islands and tidal zones. Hidden coasts are buried under swift reclamation efforts or long, slow geological processes. Breeding grounds and habitats. Advanced coasts. Hard concrete edges. Harbours. Quays. Seawalls.

In Havbrevene (2018) by Siri Ranva Hjelm Jacobsen, the two sisters called the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean exchange letters about the myth of Icarus, the little human creepy-crawlies, and a deep-time plan to once again cover the planet in blue, facilitating an “oceanic perspective” on the history of humans, the Earth, and its elements (Frank 2021). In one of their exchanges, the older, wiser Atlantic, surprised by nothing, tells her younger sister, the glitter-loving Mediterranean, who adores Icarus and streams of animals, to think of the coasts as a costume. All the seas are in disguise, waiting to turn the planet once again into a mirror ball, a covering soon to be lifted when the waters rise to reclaim the Earth:

Think of the coasts as a costume, all us seas are in disguise. You will not be lonely, I promise you that. We will become a mirror ball, an eye, a mother (translated from Jacobsen 2018, 37).

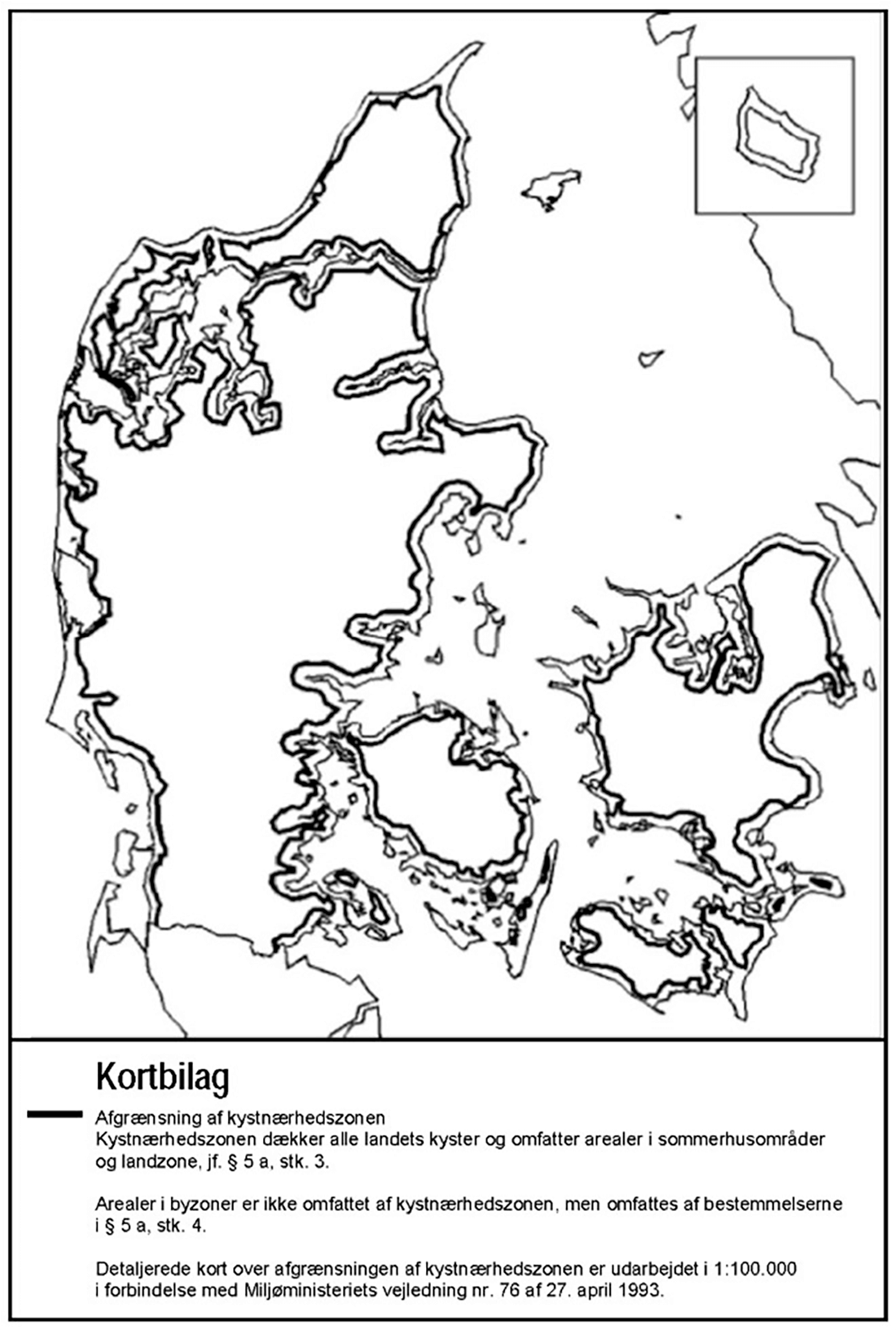

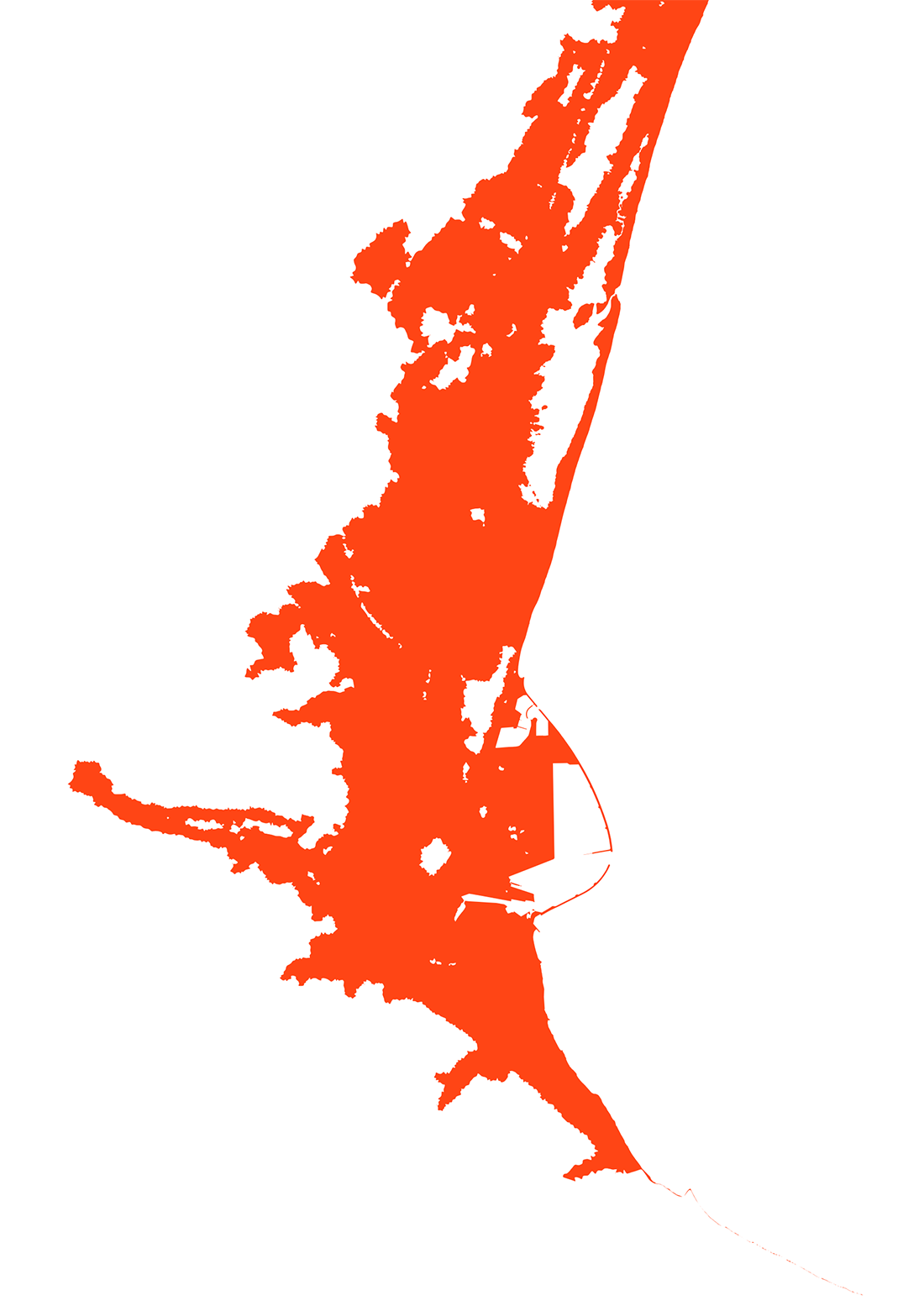

In Danish legislation, the protection of coastal landscapes, not against cunning oceans but from human interventions, has been “a major concern” for decades, as Helle Tegner Anker notes (2020, 85). This protection reflects a dual focus on environment and recreational welfare values. The coast is considered a national priority and is protected through the (generally) 300 metre wide Coastal Setback Zone and the 3 kilometre wide Coastal Planning Zone. The latter is not a prohibition zone but a planning framework under which municipalities must ensure that new construction is directly related to its coastal context (Anker 2020). These protective measures, however, are under pressure from commodifying agendas of tourism and local development.

The intensity of sea level rise has increased since Rachel Carson described this in The Edge of the Sea (1955), but the call for poetry, natural sciences, and architecture to contribute imaginaries for the coast continues into the present century. While the coast has always been associated with risk, such as rip currents, groundings, and floods, contemporary concerns of flood risk management, adaptation, protection, and retreat strategies are introducing new discourses, engagements, and perspectives.

The coast is not only a line or a zone. It is shifting, porous, dramatic, and calming. A space of multi-species entanglement, an idea, and a drama. How one imagines, plans, inhabits, and cares may be part of shaping the futures of the shorelines we share.

References

Anker, H. T. (2020). Denmark. In R. Alterman & C. Pellach (Eds.), Regulating coastal zones: International perspective on land management instruments (pp. 83–101). Routledge.

Binderup, M. (n.d.). Begrebet kystzone i Naturen i Danmark. lex.dk. Retrieved April 7, 2025.

Dinesen, I. (pseudonym for Karen Blixen) (1934). The Monkey in Seven Gothic Tales.

Harrison Smith and Robert Haas. New York.

Burcharth, H. F., & Nielsen, N. (n.d.). Kyst. Den Store Danske, lex.dk. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

By-, Land- og Kirkeministeriet. (2024, as amended). Planning Act. Consolidated Act no. 572/2024.

Carson, R. (1955). The Edge of the Sea. In Rachel Carson: The Sea Trilogy (pp. 408–678). Literary Classics of the United States (2021).

CERC (Coastal Engineering Research Center). (1984). Shore protection manual (4th ed.). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Cohen, M. (2006). The Chronotopes of the Sea. In F. Moretti (Ed.), The Novel, Volume 2 (pp. 647–666). Princeton University Press.

DHI. (2017). Shoreline management guidelines.

Frank, S. (2021). Her regerer havet: Siri Jacobsens Havbrevene og en amfibisk verdensanskuelse. Passepartout, (42), 18–37.

Jacobsen, S. R. H. (2018). Havbrevene (1. udgave). Lindhardt og Ringhof

Lund, A. A., & Carstensen, J. S. (2023). Preface. In A. Lund & J. S. Carstensen (Eds.), Critical coast (pp. 5–9). Danish Architectural Press

Mathur, A., & da Cunha, D. (2020). Wetness is everywhere: Why do we see water somewhere? Journal of Architectural Education, 74(1), 139–140.

Sammler, K. G. (2020). 3. KAURI AND THE WHALE: Oceanic Matter and Meaning in New Zealand. In I. Braverman & E. R. Johnson (Eds.), Blue Legalities: The Life and Laws of the Sea (pp. 63–84). Duke University Press.

Sandemose, A. (1953). Vi pynter os med horn (C. Clausen, Trans.). Aschehoug. (Original work published in Norwegian as Vi pynter oss med horn)

Tuxen, J. P. (2025). Da havet åd fjorden. Dagbladet Information.