Airs

Related terms: atmospheres, air, wind, air pollution, air quality index, livable cities, climate change, greenhouse gases, mortality, breathing, life force, air quality management.

Thinking of the air as a neutral, natural, universal, or global condition is not enough in the world we inhabit today. How we relate to the air has many manifestations. Air signifies the invisible gaseous layer surrounding the Earth, in which we breathe in disparate ways. During pandemics, it carries airborne viruses that have unequal effects globally. It also refers to one of the four basic elements in ancient and medieval philosophy. In addition, the planetary atmosphere is the site where greenhouse gases (GHG) from the burning of fossil fuels make the phenomenon of climate change and its unequal effects real. Using the term ‘airs’ in the plural signifies not only the variety of atmospheric entanglements we embody but also the possibility of their coterminous existence.

The air is not merely a substance that matters differently, but should be conceived as gathering tendencies towards structures of feeling: practices, thoughts, ideas, sensations structured by the elemental (Adey 2015, 66). A tricky and slippery substance, air remains dynamic, fleeting and ephemeral while tending to material, discursive and affective formations (Choy 2018). ‘Airs’ is a means to list some possibilities of how all that is the air comes together (with other material entities and discourses) in formulating more-than-human relatedness.

To demonstrate this, I will engage with air in three ways: (I) air quality management and air-induced ailments, (II) climate change and planetary atmospheric relatedness, and (III) understanding of vital airs or winds constituting life force. These airs have evolved through epistemic regimes such as biomedical science, urban and climate change policy, traditional medicine and religious belief systems that make sense of our relationship with air. While I discuss them separately, as ‘airs’, they exist simultaneously and intersect in the contemporary.

(I) Advanced scientific understandings of the relationship between particulates and gases in the air and their effect on human and environmental health have made Air Quality Management an important policy mandate globally. This has led to new practices of bureaucratisation, the development of classification categories to understand the quality of air in a place and a heightening of the related prevailing affective characteristics.

“Delhi Saw 209 'Good To Moderate' Air Quality Days In 2024” (Press Trust of India 2024) are headlines that have become common in the last decade in India. The correlation between the quality of air on a day and whether it is rendered ‘good’ or ‘moderate’ is based on the Air Quality Index (AQI). The AQI is a weighted average that relates levels of pollutants in the air to human health. The range of what ‘good’ to ‘severe’ levels is for the AQI is fixed by the national government and varies globally (see Figure 1). This is done keeping in mind the state of air in a country, trends of air pollution, and designing realistic policy goals for improving air quality (CPCB 2014).

The AQI is a science-based assessment of air quality. It has acquired traction as a means to judge if residents should plan outdoor activities with or without the use of masks that filter airborne materials. The success and design of air quality management policies are measured through the AQI, and it serves as a metric to compare what makes a city more livable. In short, the AQI has become a means of understanding progress, development and policy.

Figure 1: AQI breakpoints courtesy of https://urbanemissions.info/delhi-india/delhi-ambient-monitoring-data-timeseries/

Figure 1: AQI breakpoints courtesy of https://urbanemissions.info/delhi-india/delhi-ambient-monitoring-data-timeseries/

These advances have emerged from a rise in awareness about air-induced ailments, such as asthma (Kenner 2018), tuberculosis (McDowell 2024) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Wainwright 2017). While they affect populations unequally, it is the universal act of breathing that ties in air, bodies and breathing as porous becomings. This was heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic, wherein ‘[s]hared air and the mingled breath of intimacy’ became ‘recognisable markers of our mutuality of being’ (Fergie et al. 2020, 58). Breath and breathing connect consciousness and the body, self and other, and allow for an ethics of difference to emerge (Irigaray 2001). Our intimacy with air manifests in various ways through our material bodies, notions of contagion, and the political possibilities of development and progress that signify the general ambience of places and modes of living with air.

(II) Even though the links between air pollution and climate change are established as an undeniable fact in international science and policy discourse (UNEP 2019), this connection does not figure prominently in air quality management discussions. In responding to climate change, it has been recognised that the gaseous layer enveloping the Earth is not only an object of human knowledge but a historical force in its own right that has structured and been structured by human action and life (Carson 2020).

As a geological force, humankind has been reconceptualised as capable of causing change to the planetary climate through the unabated emissions of GHGs. Simultaneously, other geological forces such as soil fertility, availability of natural metals and materials, and biodiversity competition have limited human activities such as monoculture cultivation, energy and resource extraction and infrastructural expansion (Chakrabarty 2021). In the late 1990s, this more-than-human intertwining led to Indian environmental activists proposing the need for tradable, quantified per-capita rights to pollute the atmosphere with GHGs, as a general proposal for an equitable and comprehensive way to reduce GHGs (Agrawal and Narain 1999). This logic has miscarried in carbon markets, which are financial trading systems where the right to emit GHGs is bought and sold. Carbon trading, though framed as a solution, reinforces existing power structures and inequalities that mimic historical emission practices. A few energy-intensive economies continue to contribute to climate change at the expense of the world’s impoverished populations. The critique of carbon markets bestows a human dimension to the planetary atmosphere and has become a fundamental way to make sense of anthropogenic climate change (Whitington 2016). The carbon footprint is a direct rendition of this link. Every activity we undertake, from travel through dietary choices to our lifestyle or even just breathing, contributes to our carbon footprints while making human-atmospheric relatedness profound.

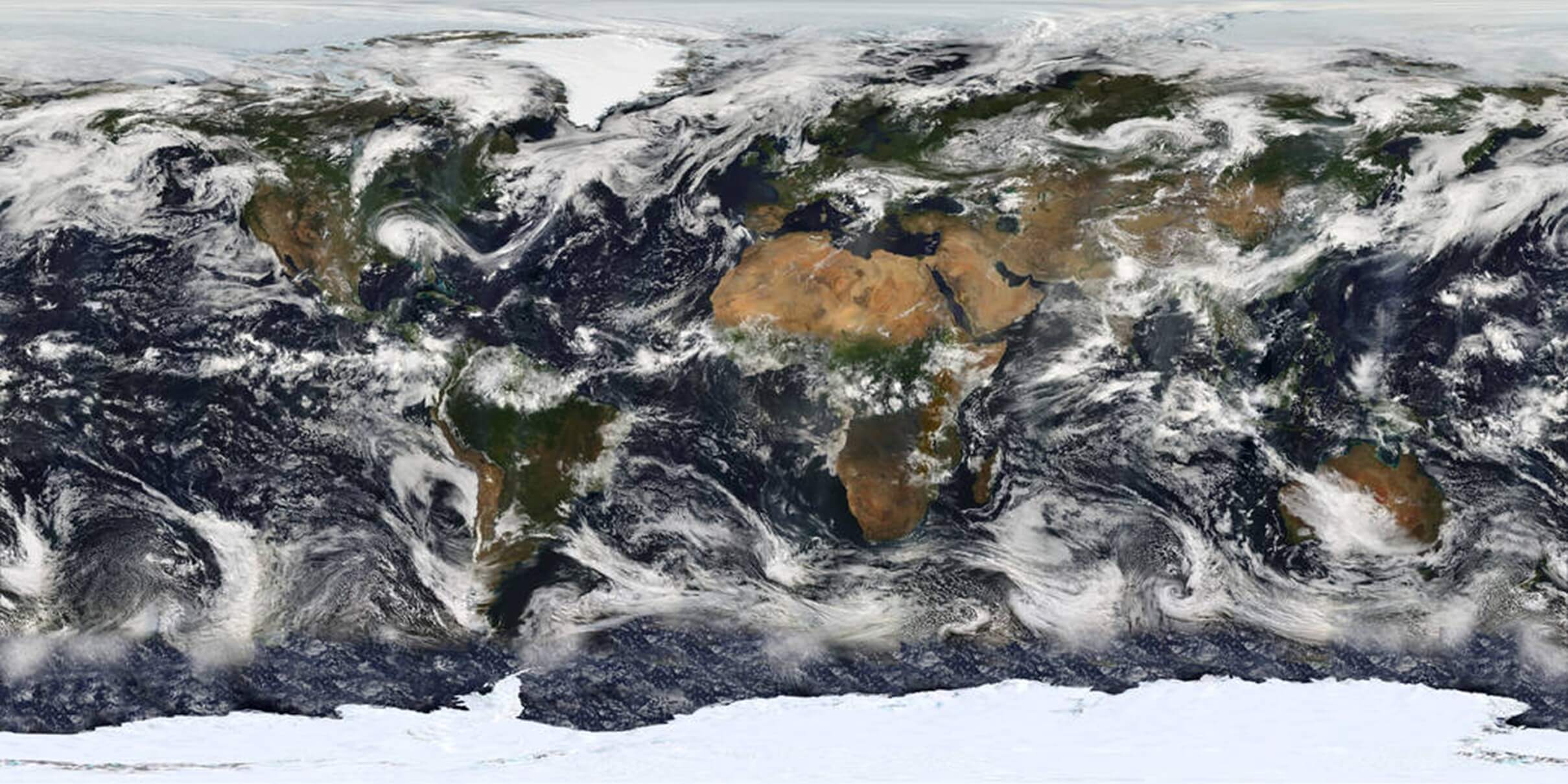

The planetary dimensions of atmospheric movements transcend the individual (Edwards 2010). To believe in the carbon footprint or that our daily activities will impact the atmosphere, we must be able to imagine the planetary climate, made possible by climate simulations and satellite images (Knox 2020) (see Figure 2).

Viewing the Earth as a dynamic, fragile and complex system has challenged the authority of technocracies and their ability to control Earth systems. This uncertainty folds itself into all ecological relationships (Whitington 2018). Our ability to imagine climate futures then emerges from a contest between aspirational development and a complex planetary system that resists taming. Paying attention to human–atmospheric relatedness allows us to engage with these dynamics, without ignoring their gross ethical and unequal implications. Climate change raises questions about intergenerational justice and the responsibility for addressing the crisis as it disproportionately affects vulnerable populations and exacerbates existing inequalities.

(III) Beyond the planetary, air in movement connotes spirits and the universal flowing life force. Metaphysical elegies and philosophical musings on the Latin spiritus (breath of life), the Hebraic ruah (breath or air), the Greek pneuma (breath of life or life in the Spirit of God), the Sanskrit prana (vital airs or winds), and the Chinese qi (energy) have been written since the times of antiquity through mediaeval saints to modern theologians, healers, and scholars. The Sanskrit terms, prana and vayu, also point to these imbrications. Found in the earliest Sanskrit texts, human breath, or prana, was understood to be a manifestation of the cosmic wind (vayu); furthermore, this prana was present when there was life and absent when there was no life. Hence, it was considered to be the life-breath (Zysk 2007, 106). The notions of prana and vayu approximate the Chinese concept of qi, variously translated as ‘air, breath, energy or primordial life source’ (Chen 2003, 6). Cultivation and control of qi are central to the modern healing practice of qigong, which involves breathing techniques, various forms of bodily movements and mental visualisations. By understanding moving air as a sensorial experience, in which all things are linked and events happen for a reason, the air becomes a metaphysical connective medium.

Airs exist variously and simultaneously in our lives. Here I have alluded to three possibilities that are not only conditions of life but mark and make our relatedness in and with the world. These material, discursive and affective formations inform our actions as moral-political beings. Climate change advocacy, air quality management, human mortality policy, and religious and community ascriptions are some forms of contemporary political practice that are realised through human-atmospheric entanglements and their attendant possibilities.

References

Adey, Peter. 2015. ‘Air’s affinities: Geopolitics, chemical affect and the force of the elemental’. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 5, 54–75.

Agrawal, Anil, and Sunita Narain. 1999. Green Politics. New Delhi: Centre for Science and Environment.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2021. ‘Postscript: The Global Reveals the Planetary: A Conversation with Bruno Latour.” The Climate of History in a Planetary Age, University of Chicago Press.

Chen, Nancy N. 2003. Breathing Spaces: Qigong, Psychiatry, and Healing in China. New York: Columbia University Press

Choy, Timothy. 2018. ‘Tending to Suspension: Abstraction and Apparatuses of Atmospheric Attunement in Matsutake Worlds’, Social Analysis 62, 4 (2018): 54-77. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2018.620404

CPCB (Central Pollution Control Board). 2014. National Air Quality Index. Central Pollution Control Board, New Delhi.

Edwards, Paul N. 2013. A Vast Machine. Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming. MIT Press.

Fergie, Deane, Rod Lucas, and Morgan Harrington. 2020. ‘Take My Breath Away’, Anthropology in Action 27, no. 2: 49-62.

Irigaray, Luce. 2001. “From The Forgetting of Air to To be Two”. Translated by Heidi Bostic and Stephen Pluhacek. In Feminist Interpretations of Martin Heidegger, edited by Nancy J. Holland and Patricia Huntington, 309-315. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press

Kenner, Alison. 2018. Breathtaking: Asthma Care in a Time of Climate Change. Minnesota University Press.

Knox, Hannah. 2020. Thinking Like a Climate. Governing a City in Times of Environmental Change. Duke University Press.

McDowell, Andrew. 2024. Breathless. Tuberculosis, Inequality and Care in Rural India. Stanford University Press.

Press Trust of India. 2024. “Delhi Saw 209 'Good To Moderate' Air Quality Days In 2024” Press Trust of India. 31st December, 2024.

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme). 2019. Air pollution and climate change: two sides of the same coin.

Wainwright, Megan. 2017. ‘Sensing the Airs: The Cultural Context for Breathing and Breathlessness in Uruguay.’ Medical Anthropology 36, no. 4: 332-347.

Whitington, Jerome. 2016. ‘Carbon as a Metric of the Human’. PoLAR, 39: 46-63.

Whitington, Jerome. 2018. ‘Is Uncertainty a Useful Concept? Tracking Environmental Damage in the Lao Hydropower Industry’. Platypus. Accessed 7 February 2025.

Zysk, Kenneth G. 2007. ‘The Bodily Winds in Ancient India Revisited.’ Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13: S105-S115.